Great Slowdown: Former CEA says lower lending rates won’t work

The Indian economy is headed for the ICU and traditional methods of tackling a slowdown, such as monetary and fiscal stimulus, are not going to cure the malaise.

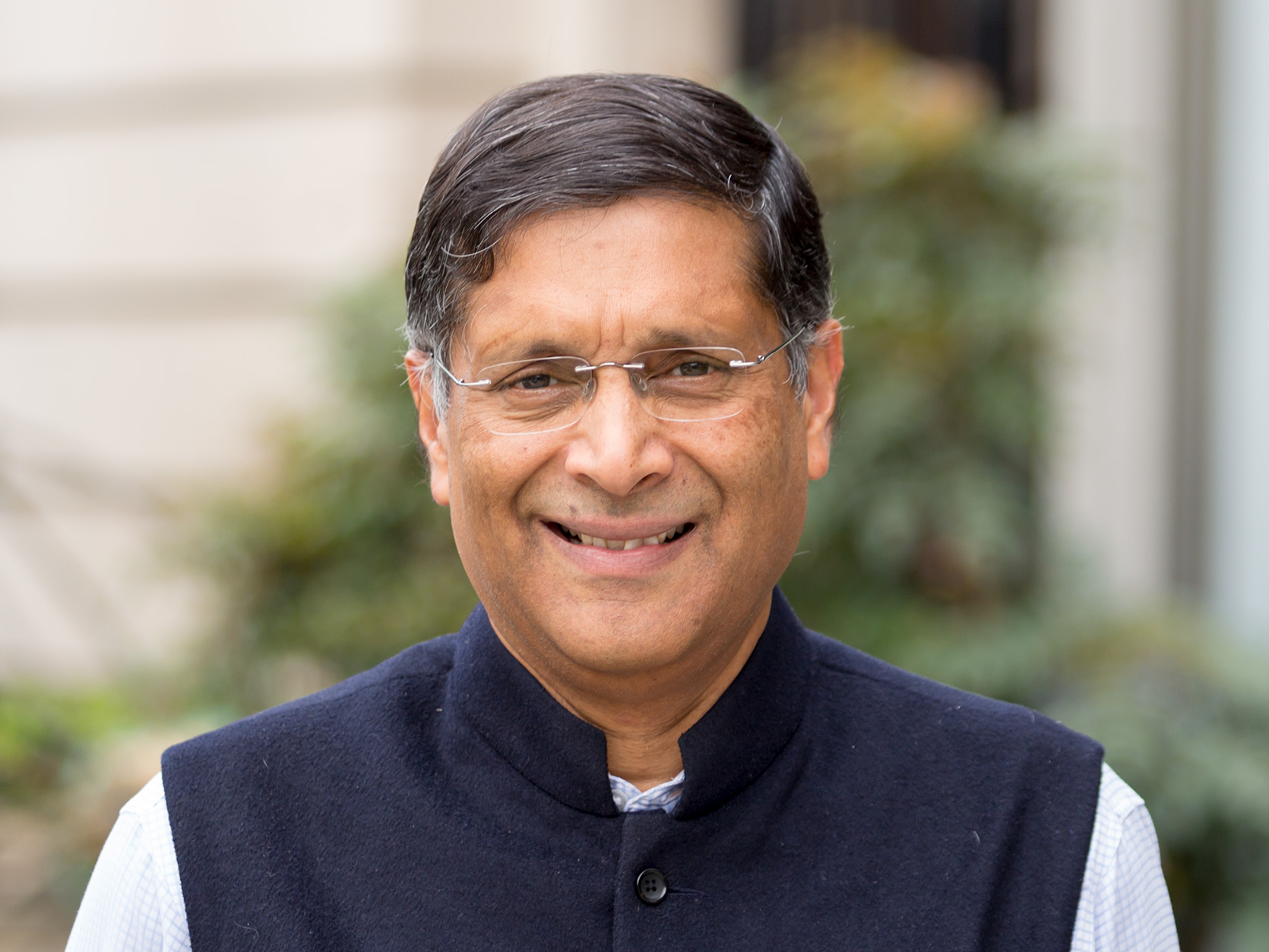

In a working paper for Harvard, India’s former CEA Arvind Subramanian and colleague Josh Felman have termed the current state of affairs as the ‘Great Slowdown’, the worst India has seen in nearly three decades.

They have argued against any cuts in personal income tax rates well as fiscal expansion; the two economists have also warned that the typical tools for tackling slowdown won’t work in the present case.

Also read | Government may rationalise personal income tax rates

Instead, they have suggested strengthening of the oversight mechanism for non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) after performing a fresh asset quality review; strengthening the bankruptcy code; creating bad banks for power and real estate sectors and shrinking India’s public sector banks through greater private sector participation.

It is pertinent to remember that despite its extreme reluctance to even acknowledge that the Indian economy is going through an unprecedented crisis, the NDA government has recently begun taking monetary as well as fiscal steps to boost growth.

Also read | Central bank’s pause on repo rate cut signals slide in economy

For example, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has already cut repo rate five times successively. On the fiscal side, the government has been offering sector specific packages and has also brought down the corporate tax rate significantly. While these measures may have helped somewhat, it is clear that these have had limited impact and growth continues to slide. The GDP growth for the July-September (Q2) quarter came in at 26 quarter low of 4.5% and the RBI has been continuously downgrading its own forecast for full year GDP growth.

Also read | Too early and little data to indicate economic revival yet

As the government fumbles over the economy, the enumeration of the ‘Great Slowdown’ and the remedies suggested by the former CEA should come as some relief. That is, if the government at all listens to the advice in this working paper. The two authors have acknowledged the role of several well-known Indian economists and experts in shaping their opinions for this paper. This list includes former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan, Nandan Nilekani, economists Milan Vaishnav and Pranjul Bhandari and journalists TN Ninan and Ashok Bhattacharya.

Subramanian and Felman have noted that India’s near economic collapse has been caused by both, structural weaknesses and cyclical factors. They have drawn up a list of things to be done and another list of things which should not be done in the present circumstances. They two sound incredulous at the extent of the slowdown, which is seemingly hard to explain.

Also read | Ground reports of a downturn

“The situation is puzzling and frustrating in equal measure. Puzzling because until recently India’s economy had seemed in perfect health, growing according to the official numbers at around 7%, the fastest rate of any major economy in the world. Nor has the economy been hit by any of the standard triggers of slowdowns… Food harvests haven’t failed. World fuel prices haven’t risen. The fiscal has not spiralled out of control. So, what has happened — why have things suddenly gone wrong?” Subramanian asked.

First, a look at what not to do to tackle the ‘Great Slowdown’

Rate cuts: The current debate revolves around whether the RBI has scope to lower interest rates further, with some arguing that the central bank needs to give the sluggish economy more help, while others worry more about the recent revival in inflation. This debate is misguided: both views are wrong. The problem is the transmission mechanism is broken, and as long as repo rate cuts are not translated into lending rate reductions, policy easing will neither provide support to the economy nor give much boost to inflation. It will remain ineffective.

Income tax relief: Tax cuts are easy to make as they are politically popular. But precisely for that reason they are very difficult to reverse. And from a long-term point of view, it is far from obvious that fiscal resources should be devoted to favouring a small share of the population, who are by no means amongst the most deserving. In fact, structurally, India should be thinking of ways to bring more taxpayers into the income tax net. It should not be raising exemption limits.

Also read | FM’s measures to ‘pump prime’ economy will cost revenue collection target

Fiscal stimulus: The space for fiscal stimulus doesn’t exist. The government is starting from a weak fiscal situation, much weaker than the headline figures suggest. India’s consolidated fiscal deficit was close to 9% of GDP in 2018-19 and this year’s outcome will surely be worse. In recent years, the government has been unable to reduce its debt-to-GDP ratio, despite rapid nominal GDP growth. If growth remains low while the “true” deficit reaches double digits, debt sustainability concerns will soon follow.

And a list of what is to be done

Fresh asset quality review: The first AQR done in 2016 – which lead to a sudden spike in India’s banks reporting NPAs – obviously could not identify all stressed assets. Ever since ILFS defaulted — despite its solid AAA rating — investors have worried that corporates and NBFCs might have underlying, unseen solvency problems and therefore have been reluctant to purchase NBFC debt. India must come clean on the entire financial system. There needs to be a comprehensive review of the financial health of the NBFCs and mutual funds, and even for the banks because a new wave of stress has arrived, which is turning previously good assets into bad ones.

Also read | Economy hit as private consumption, govt spending lose impetus

Improve IBC: The IBC process needs to be reinvigorated and this requires overhauling the framework to change the incentives of the main players: bankers, promoters, and the judiciary. Only wilful defaulters should be barred from bidding for assets and Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) should be opened up to non-bank creditors, so that any firm that has not been paid can press its recovery claim at the DRTs, rather than clogging the IBC system. Also, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (which supervises the IBC system) should allow much more bankruptcy data to be available. The two authors have also suggested creation of bad banks for power and real estate sectors.

Recapitalisation: A major overhaul of the oversight mechanism for NBFCs and banks is needed. Additionally, shrinking the public sector bank space would be prudent – government could allow more private participation in PSBs.