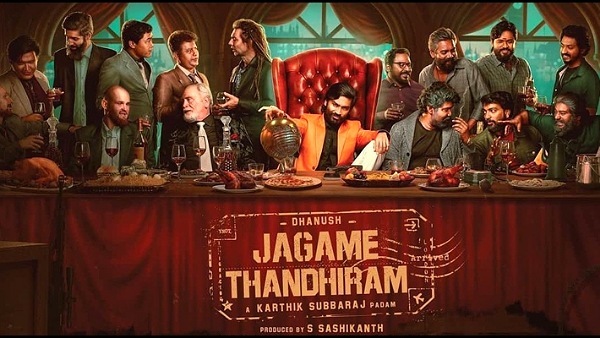

Jagame Thandhiram stretches fantasy to a break point as Tamils ‘colonise’ London

If someone who has never visited London sees the latest Tamil flick Jagame Thandhiram (in a cunning world) one can’t blame them if they imagine this vibrant, colonial yet modern capital to be a violent gangsters’ den, where you can shoot dead your enemy, slash the neck of your rival and run a compact militia armed with an eclectic mix of the latest weaponry and country-made bombs.

And, err… the police? They don’t exist. Yes, they do but in a marginal kind of way – you may occasionally spot a police car in the background with sirens blaring and probably accompanied by an ambulance. But they are not investigating anything, not even a spate of murders that dot the plot.

London, as we know it, may be identified with Scotland Yard, the world’s mother of all detectives. But in the London of Jagame Thandiram, there’s nothing of that kind. Important people get shot at, killed, bombed and die by the dozen periodically in the Scotland Yard’s own backyard, but its detectives are conspicuous by their absence.

Britain may have colonised India and Sri Lanka at least three centuries ago or thereabouts, leaving both countries some 75 years ago. It may not have been meant to be that way, but it looks as if filmmaker-director Karthik Subbaraj uses the script to “colonise” London, and show the “whites” what it means to be colonised. It is as if Tamils from Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka have simply overrun London, taken over its streets and are running the show.

Also read: High-voltage shootouts in Jagame Thandhiram & a solemn Sherni

When the protagonist Suruli, played by top star Dhanush, goes strutting around on the streets of London, the common white British folks are almost nowhere to be seen. The colonisation is complete. Yes, there are gang members who are white and possibly British, but they are mostly props. Imagine the Brits as mere props in their own country!

Yes, movies are those special spaces where the audience is routinely called upon to “suspend disbelief” but Jagame Thandiram stretches this plea to a point where even fantasy struggles to survive.

The movie is tailor-made to satisfy the protagonist’s fantasy and vanity.

To be fair, the script makes no bones about it from the very start. For example, all it takes for a speeding express train to rumble respectfully to a halt is a jalopy decked in wedding paraphernalia with Suruli, standing arms crossed unflinching in the middle of the railway track as the intimidating engine slows to a stop a feet away from him. Such is the power of Suruli, the young don, who does one better than Kabali, a role played by his father-in-law Rajinikanth, in the 2016 flick – that also had an underlying Tamil diaspora theme.

In Jagame Thandiram, a top-ranking London underworld chief, Peter Sprott, played by James Cosmo, is looking for a Tamil-speaking character to take on a rival Lankan Tamil gang. His scout arrives in India, plucks out local boy Suruli from the boondocks of Tamil Nadu and delivers him to Peter on the trot. The only concession to reality is Suruli’s inability to speak the Queen’s English and therefore is constantly accompanied by a Tamil-English-Tamil translator. Neither Peter speaks Tamil nor Suruli English, and that, thankfully is largely sustained through the film.

Also read: Vetrimaaran on Vada Chennai, it’s not a gangster film

The tempo of any film depends on the quality of editing. But Jagame Thandiram takes this truism several steps forward, or backward, depending on how you want to see it. In one frame, Suruli is in Tamil Nadu. The next, he is in London right in front of Peter. Right through, the director has taken similar liberties – people come and go as per the screenplay’s convenience. One moment, we think Suruli’s mother is in Tamil Nadu yearning for her son. The next, she is in the heart of London all set to sing and dance with him.

The screenplay has done away with the useless “connecting” bits of film time, like arriving in London etc. It’s like a switch – one second, Suruli is crying over the body of a slain friend, the next second the entire regalia of a Tamil funeral procession with the customary dancers and drummers takes over a remote part of the London landscape.

Before the viewers (rightly) conclude that the movie is only about promoting Suruli, and nothing else, the scriptwriter brings in the Lankan Tamil diaspora bit so that it can work as a fait accompli if anyone dares question the purpose of the film.

A racial conflict is purportedly on between Peter, a white rightwing don and Sivadoss, the chief of a Lankan Tamil gang who is helping refugees from his country enter London. Suruli finds himself on the side of Peter, a self-avowed anti-immigrant and xenophobe. Suruli, after much action and film time, realises he should have logically been on the other side (representing the Tamils). He attempts to make amends. Whether he succeeds or not is the rest of the film.

Fundamentally, Suruli can do no wrong – even when he is patently on the wrong side of the justice divide. From under his dhoti, and presumably from his innerwear or thereabouts, he can pull out a pistol and shoot dead an individual and walk away nonchalantly, even with a deliberate swagger.

As with Rajini’s Kabali, who survives even after getting shot point-blank, Suruli gets into a firefight resulting in multiple shots in the chest. He falls into a water body, and when the viewer wonder what’s going to happen next, he’s safely tucked away in a bed. After a cursory bandage, a few frames later, he is back in business – the injuries on his chest flicked away like dust from his body. At this stage, the audience fervently needs to suspend disbelief to continue through the film. Suruli puts to shame the potency of a gun and the bullets in it. He makes you even wonder why people die when they are shot.

Also read: A ‘Mandela’ is required to restore India’s electoral morality

The comfort of the darkened insides of an insulated standalone cinema house is long over. It probably slipped the mind of the filmmaker that we are seeing Jagame Thandhiram on Netflix at a time when the world’s best cinema is jostling for attention on OTT platforms. So, comparisons are natural and inevitable.

When the neighbouring state of Kerala is making waves with such impeccable and classy movies like Joji, Nayattu and Kumbalangi Nights, Tamil cinema is still kitschy, stuck in a time warp – dishing out outlandish cardboard characters and scripts to boost the vanity of individuals rather than using the medium to come up with truly world-class stuff.

Jagame Thandiram, sadly, turns out to be the latest example of this.