Trump's world: Are global leaders sleepwalking into World War I-like crisis?

Rising nationalism and reckless military interventions are reminiscent of pre-1914 order, even as nuclear deterrence and economic ties offer trhe only off-ramps

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it: George Santayana

On November 11, 2018, the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War (1914-18), French President Emmanuel Macron made stark comparisons between the situation that led to the War and present geopolitics, thanks to an alarming rise of nationalism on either side of the Atlantic.

“Old demons are resurfacing,” the centrist French leader said at an event in Paris, warning that “patriotism is the exact opposite to nationalism”.

One of Macron’s targets in the high-profile audience was his American counterpart Donald Trump, then serving his first term. In fact, it was just in the month before that the mercurial Republican declared at a rally in Houston that he is a “nationalist” and treated “globalists” with disdain.

Also read: Iran's plight reflects disunity in Muslim world | Worldly Wise

Going by Trump’s unilateral aggression in his second term so far — be it brutal trade tariffs or direct military interventions, particularly what Washington did in Venezuela, or indirectly triggering Israel — the US President has dealt a blow to the rules-based global order and revived the ghosts of the pre-1914 world. Real or potentially devastating acts undertaken by other major powers of this era, such as Russia (in Ukraine) and China (in Taiwan), have added to the danger.

The US special operation in Venezuela is a clear indication that since great powers still seek security, relative gains, and strategic depth in regions they dominate, the spheres of influence theory has always been there.

While there are big challenges that make the current world order vulnerable to a major disruption today, as it was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the onus also falls on the intent of major world leaders to ensure that peace prevails. As the stories unfolding in Ukraine, Venezuela, and Gaza suggest, are they behaving responsibly enough to prevent a World War I-like situation today?

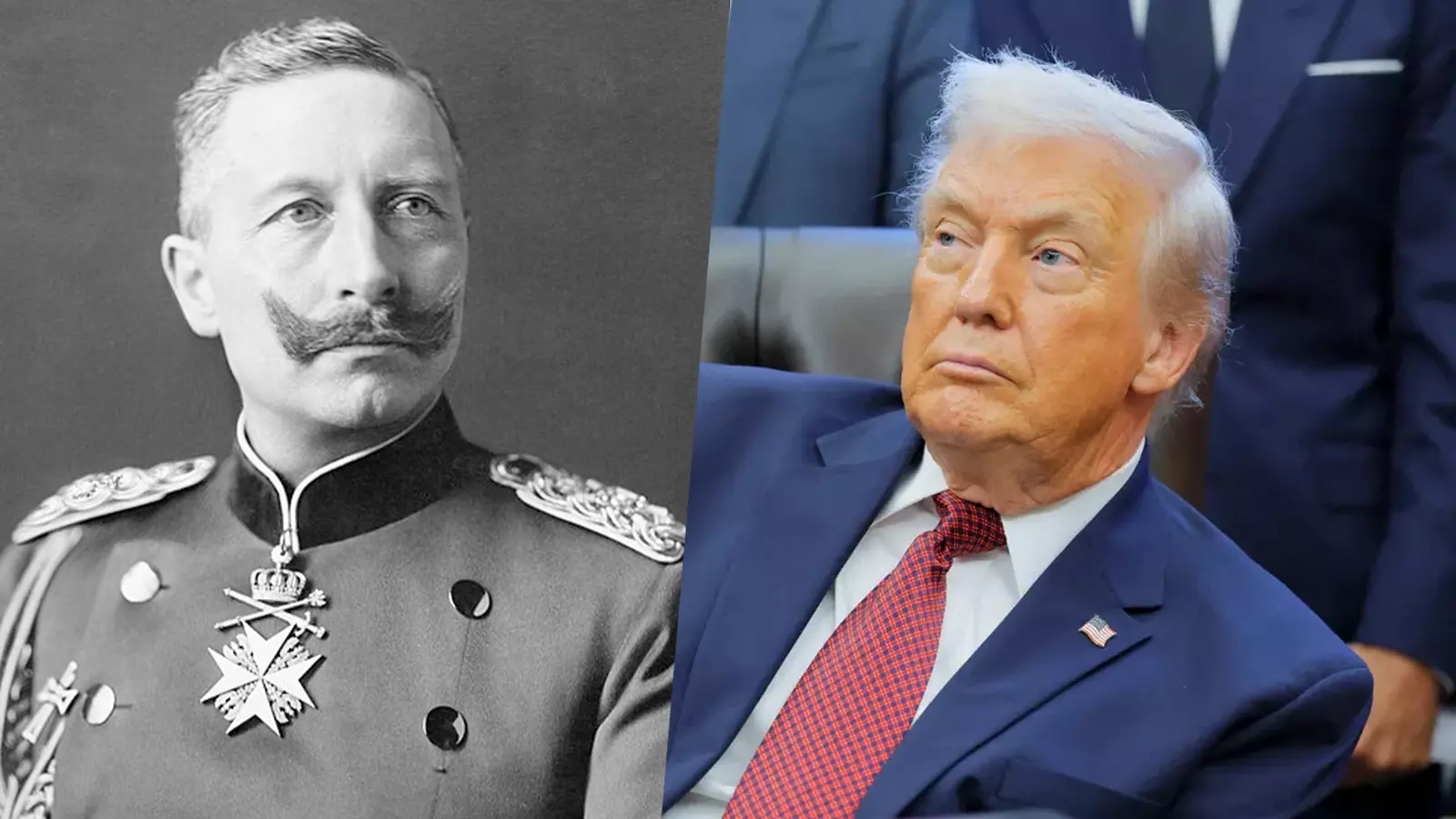

Is Trump the new Wilhelm II?

One of the central characters of the chaotic world politics today is undoubtedly Trump. Given his eccentric and impulsive nature, many observers have compared him with a similar leader who existed 112 years ago — Kaiser Wilhelm II, Germany’s wartime and last emperor, even though the two have operated in vastly different political systems (Trump’s democratic against Wilhelm’s monarchical).

Sir Christopher Clark, an eminent Cambridge University historian and the author of The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, is among them. The scholar sees similarity between the current American ruler and the former German leaders.

Also read: Trump should know why Iran is not Venezuela

In a November 2018 article on The GroundTruth Project, where Clark was cited, he said, “The Kaiser in many ways is very, very like Donald Trump with an almost pathological inability to express or possibly even to feel empathy with other human beings.”

MAGA mania

Col Ramani Hariharan from the Chennai Centre for China Studies has studied the Trump phenomenon in detail. Speaking on the leader’s contributions to global chaos, be it through actions (Ukraine) or words (Iran, Greenland or Canada), he said the US president’s core philosophy has three components — MAGA (Make America Great Again) agenda, transactional realism and populism. He has used them dangerously to promote nationalism at the expense of globalism.

“The MAGA agenda uses ‘America First’; nationalism as its war cry, and rejects globalism. It favours a unilateral approach to protect US interests. To protect American identity, it focuses on strict immigration controls, treating them purely as a law and order problem,” he told The Federal.

“Trump uses transactional realism in his dealings, as explained in his 1987 book The Art of the Deal. It involves using business-centric logic in governance, viewing political and diplomatic transactions as zero-sum competition.

“The third component, Right Wing Populism, has its roots in 'aggrieved entitlement', as evident from Trump’s social media supporters’ writings. Its anti-establishment champions frame their political action as a retributive justice for those affected."

Putin's imperial designs

If one looks at Vladimir Putin of Russia, he sounded more like a benign statesman on several occasions before the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. In October 2018, the Russian leader said at an event in Sochi that he sees himself as a nationalist who seeks preservation of a multi-ethnic Russia, and doesn’t favour the “caveman” variety.

Also read: Trump’s raw power politics and what it means for India

However, his army’s action in Chechnya, Crimea and currently Ukraine showed that the strongman at the Kremlin actually believes in a monolithic Russian nationalism that doesn’t hesitate to crush anything that it feels is not conforming to the identity it prefers.

Jakub Janda, director of Prague-headquartered European Values Center for Security Policy, and a strong critic of Russia, said Moscow’s interventionist actions are primarily guided by Russian imperialism, as it wants to reconquer much of Central Europe, which was under its occupation during the times of the erstwhile Soviet Union.

While stressing that the US and China will dominate the multipolar world, which will also have other important nations, including India, Eric Solheim said technology and economics will be at the centre of global rivalries in the days to come.

The story is not much different from China. In 2018, Chinese President Xi Jinping got rid of term limits to extend his stay in power. He also adopted a nationalist stance as Trump’s tirade against China over trade grew. As Beijing turned more nationalist, its traditionally aggrieved neighbours started feeling the heat more. The foremost of these is Taiwan, which China encircled militarily once again in December 2025 in an act of intimidation.

The Realist school of thought

Around the middle of the 20th century, Hans J Morgenthau, an international relations scholar, came up with his notable work Politics Among Nations, in which he established that power is the dominant goal in international politics and national interest is defined in terms of power. The State remains the central character of his theory, and it cares little about moral laws while pursuing power.

While Morgenthau’s theory was validated by the two world wars, the stark reality of 2026 is not too far from what he said nearly eight decades ago.

Also read: Why has India stopped short of condemning US action against Venezuela?

Janda told The Federal, “Yes, absolutely, the power-first environment is what is increasingly dominating global politics today. Individual powers push for regional influence, with the US-China rivalry underpinning the global order.”

He also said global conflicts cannot be ruled out today, and they are the most probable now for several recent generations.

That such an eventuality can only be ignored at our own peril has already been proved by the military adventures of Putin and Trump, and the potential threat by China, all of which are fuelled by nationalism. All these big powers eye expansion and domination, something Europe had seen before the First World War, till it reached a point of no return.

The pre-WWI alliance systems

Before the Great War (World War 1), the British and French empires were the most powerful, colonising vast regions across the planet. Their insatiable hunger for more colonies saw the continuation of imperialism, which inevitably put them on a collision course with other European powers, including Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey (formerly the Ottoman Empire), which together came to be known as the Central Powers.

The international system today is more diverse than it was in the 1910s, but it is also more chaotic. There are no mutually resistant alliance systems today like the Central and Axis Powers.

Against the Central Powers arose the Allied Powers that included Britain, France, Russia (till its revolution in 1917) and Japan and later saw the entry of Italy and the US. Besides the major powers, there were also sides such as Bulgaria, which chose the Axis Powers.

Bulgaria’s wartime prime minister, Vasil Radoslavov, had remarked while justifying his country’s decision to join the Central Powers, “Today we see races that are fighting, not indeed for ideals, but solely for their material interests.”

Not ideals but material interests — the words strike even today, 112 years later.

What finally matters

In 1914, Serbian nationalism was a major factor behind the outbreak of the First World War, thanks to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Austro-Hungarian Empire by a Bosnian Serb, which saw one power after another sucked into the conflict, which kept on snowballing.

Also read: Explained: Why did US attack Venezuela?

The international system today is more diverse than it was in the 1910s, but it is also more chaotic. There are no mutually resistant alliance systems today like the Central and Axis Powers.

Military, political or economic blocs are there, such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) led by the West or the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) or BRICS dominated by nations such as China and Russia. But they are not mutually hostile, like the blocs during the World Wars or the Cold War. Is this lack of a traditional balance of power good or bad for world peace?

Marc Finaud, a former French diplomat who is currently with the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP), Switzerland, told The Federal, “Today, there is only one defensive military alliance, NATO, which is collective and can only act upon the consensus of all its members. The other groups have more of an economic agenda, but all are supposed to act according to the UN Charter. What makes it more dangerous than the pre-WWI context is that armed conflict among the big powers is likely to escalate to a devastating nuclear war.”

Although Finaud is not too convinced about a direct parallel drawn between the pre-WWI situation and today, he still sounded worried, saying most bilateral treaties containing the arms race between the US and Russia have disappeared, and with more number of countries possessing nuclear weapons and many investing in offensive systems capable of bypassing defences, the absence of a balance of power has made the world more unstable and dangerous.

'Tech, economics at centre of rows'

Eric Solheim, a former Norwegian minister, diplomat, and green politician, agrees that the international system unfolding today is not much different from that which existed before 1914, especially after what the US did in Venezuela, but he also sees a silver lining.

“The US’s claim of Venezuela as a protectorate is similar to the colonial era. But fortunately, the counterforces to colonialism today are much stronger than in the 19th century. The US is not likely to succeed in creating lasting protectorates,” he told The Federal, and reminded, “We need to build a rules-based order.”

Also read: Trump warns Russia-Ukraine war could trigger World War III

While stressing that the US and China will dominate the multipolar world, which will also have other important nations, including India, Solheim said technology and economics will be at the centre of global rivalries in the days to come.

According to him, hope lies in the fact that the current wars in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan and other places are catastrophic in terms of human suffering, but they are unlikely to develop into full-fledged world wars. “The most important lesson from 1914 is not to sleepwalk into conflicts. Trump has so far not shown any appetite for big wars,” Solheim added.

Professor BR Deepak from Jawaharlal Nehru University’s (JNU) Centre for Chinese and Southeast Asian Studies said today’s powers avoid direct intervention owing to reasons such as administering populations and managing conflicts. According to him, control of territory is no longer a primary source of power since capital, technology, data and supply chains matter more in today’s world.

Realism through 'other means'

“However,” said Deepak, “the US special operation in Venezuela is a clear indication that since great powers still seek security, relative gains, and strategic depth in regions they dominate, the spheres of influence theory has always been there, and has been clearly spelled by the US National Security Strategy of 2025.” He said Realism is very much alive today, but it operates more through economics, technology, and institutions and not territorial conquests.

“A global war today would likely emerge from mismanaged power transitions and technological escalation, not through imperial expansion in the classical sense,” he told The Federal.

Finaud feels that while great-power competition is mainly fuelled by the search for power or security, the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Ukraine and now possibly Venezuela show that the outcome was not necessarily positive for the hegemon that started such wars.

Can we afford diplomatic threat?

Rajesh Mehta, advisor to the Nordic Council of Indian Diaspora, who also writes extensively on international affairs, told The Federal that the ongoing conflagrations in Ukraine, Venezuela and potentially in Taiwan convey the dangerous message that territorial expansionism and imperialism are a threat to all countries today.

“Given there are already myriad threats emanating from climate change, terrorism, cyber threats and others, we can ill afford such diplomatic mayhem today. Cooperation today is not just an option but a necessity,” Mehta said.

Solheim also thinks cooperation is the way forward today to avert conflicts between major powers and the Global South, Europe and others must promote a rules-based world order, or else it will be a law of the jungle where might is right.

Today, even a slight competition between great powers can potentially turn devastating, thanks to their nuclear arsenals. However, what makes today’s international community hopeful is that there are several instruments that can check such situations.

A more elastic system

Professor Deepak agrees. According to him, war was inevitable in 1914 because “structural rigidity dominated the system and a belief that wars would be short and decisive prevailed (which, however, was not the case as leaders rapidly lost control)”.

Today, danger lurks, but the system is also more elastic. While nuclear deterrence raises the cost of great-power war to existential levels, economic interdependence, real-time communication and crisis-management experience give off-ramps that were not available in 1914, he said.

The risk today is not inevitability but miscalculation through prolonged pressure, proxy wars, technological escalation, or accidents, the JNU scholar said.