- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Over 120 deaths in 2025, why stampedes remain a recurring tragedy in India

On Jan 12, actor-politician Vijay was questioned by CBI in last year's Karur stampede case. Unfortunately, however, it was not an isolated tragedy of its kind. Experts cite overburdened infrastructure, lax enforcement of capacity limits and improper management and planning as reasons.

In September 2025, 30-year-old Suriya (identified by first name only) was one of those present at a rally called by actor-politician Vijay’s party, the Tamilaga Vettri Kazhagam (TVK), in Tamil Nadu’s Karur district. Little did he know then that it would turn out to be one of the scariest days for him and the friends who had accompanied him there.As Vijay was addressing the audience...

In September 2025, 30-year-old Suriya (identified by first name only) was one of those present at a rally called by actor-politician Vijay’s party, the Tamilaga Vettri Kazhagam (TVK), in Tamil Nadu’s Karur district. Little did he know then that it would turn out to be one of the scariest days for him and the friends who had accompanied him there.

As Vijay was addressing the audience that evening, a stampede broke out among the crowd of supporters who had waited hours, reportedly since the afternoon, to see the star-leader.

Suriya remembers being carried forward, along with his friends, as if by a wave. People pushed in all directions. “It was horrific. There were no exits since it was being held on the main road and we had not anticipated that there would be no escape from the crowd once we were caught,” he recalls.

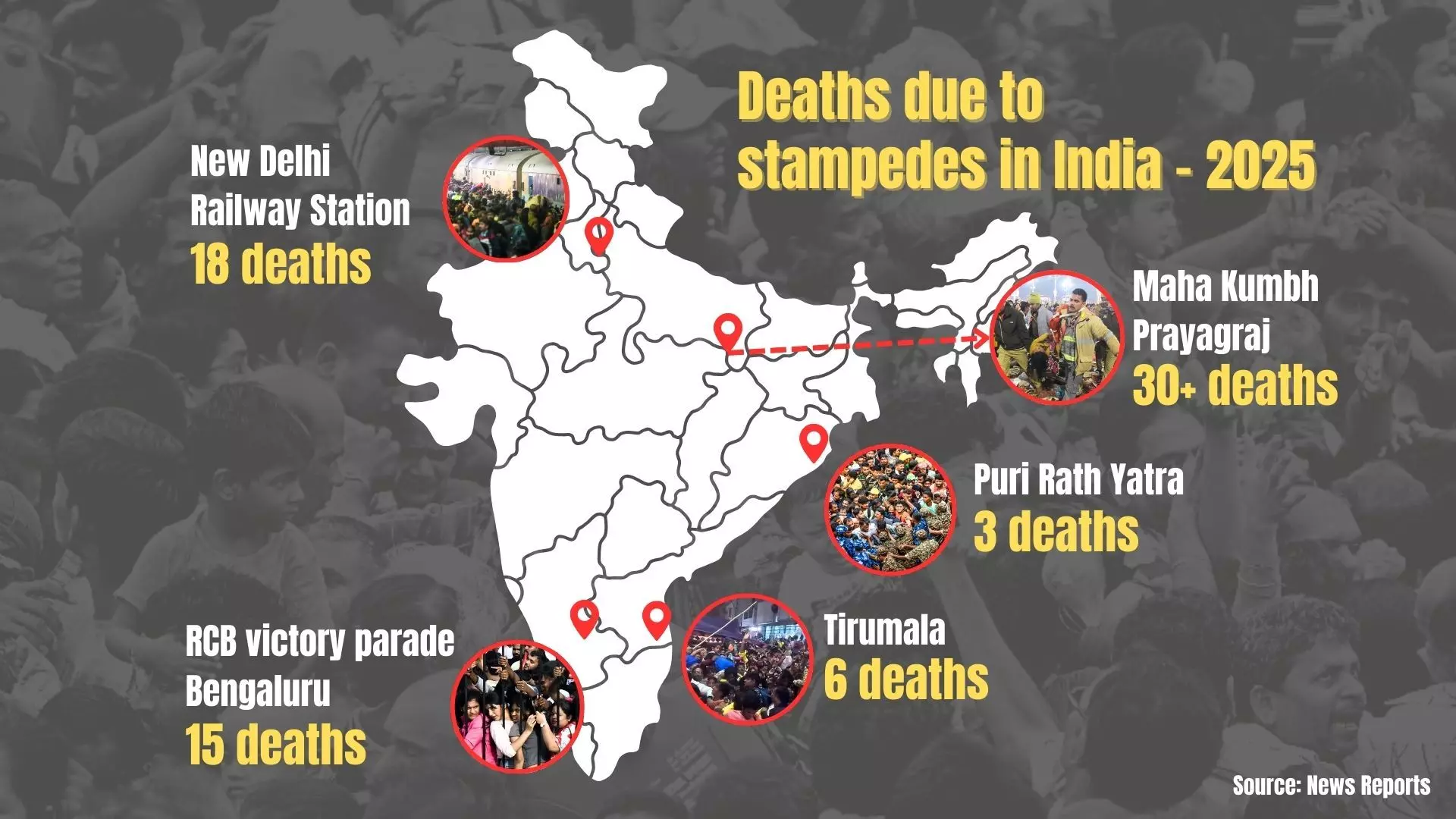

The Karur stampede was, however, not an isolated incident. From the tragedy that struck devotees at the Maha Kumbh in Prayagraj in January 2025 to the deaths at the Sri Venkateswara Swamy Temple in Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, in November, India saw a series of stampedes in 2025 that reportedly claimed over 120 lives.

Also read: Nearly six months after flash floods wreaked havoc in Dharali, why locals are yet to move on

It started with a rush for sacred darshan tokens at the Tirumala Venkateswara Temple in Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, with six lives lost in January 2025. Then, on January 29, over 30 devotees lost their lives in a pre-dawn chaos at the Sangam during the Maha Kumbh in Prayagra. Another 18 lives were lost in the rush for trains at New Delhi railway station on February 15, caused by a crowd of pilgrims desperate to reach Prayagraj for the then ongoing Kumbh Mela. The Sri Lairai Devi Temple in Goa in May was the scene of another one of last year’s stampedes, as six-seven people lost their lives as a crowd thronged to participate in an annual ‘jatra’ (festival). A victory parade for the Indian Premier League team Royal Challengers Bangaluru (RCB) in June saw 15 fans lose their lives amidst frenzied celebration at Bengaluru’s M. Chinnaswamy Stadium. The Puri Rath Yatra, also in June, saw three devotees trampled near Gundicha Temple during the divine procession. Then there was Karur, in September. And in November, nine devotees, including children, lost their lives in a stampede at the Sri Venkateswara Swamy Temple in Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, during a rush on the auspicious day of Ekadashi.

Disaster management experts emphasise on proactive measures or preparedness, proper capacity building and mock drills to avoid such untoward incidents.

"When there is a disaster, we talk about all these [preventive measures]. We have been reactive [instead of proactive] right from the beginning. When the disaster management authority was set up, it was expected that there would be a paradigm shift from our earlier rescue and relief centric approach to looking at the pre-disaster phases including prevention, preparedness and mitigation and the post-disaster phases including reconstruction, rehabilitation, long term rehabilitation and reconstruction,” says M Sasidhar Reddy, former vice chairman of the National Disaster Management Authority. “However, authorities have been focusing only on the rescue and response approach," he adds.

Devotees attempt to cross a barricade at the Maha Kumbh on the say of the stampede. PTI File Photo

Experts also emphasise on making stampede prevention a compulsory school subject, running awareness campaigns in cinemas, and persuading celebrities to stop luring massive crowds for quick profit through “exclusive” or “limited” offers. Religious events pose the toughest challenge owing to the fear of hurting sentiments.

According to reports, 2025 was the “second deadliest” in terms of stampede related tragedies in recent memory. The data journalism and fact-checking site Factly cites the National Crime Records Bureau’s Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India report to state that 3,074 people died in stampedes between 2001 and 2022 – that’s approximately 145 on average every year. Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu purportedly account for half of the total deaths in stampedes since 2001.

Take for example, the stampede at Chennai’s MGR Nagar on December 18, 2005, during a distribution of flood relief tokens at the Arignar Anna Corporation High School. The tragedy reportedly killed 42 people and injured 37, as a heavy downpour caused a surge in the crowd seeking shelter.

In West Bengal, seven pilgrims were reportedly killed and 12 others injured in a stampede that occurred in 2010, while people were trying to board a boat to go for a holy dip at the Ganga Sagar fair held in January every year. The fair reported six deaths in 2017, when devotees rushed to board a vessel at Kachuberia Jetty.

Temples, railway stations, political rallies or stadiums — all these public places have got tragic tales of stampedes to narrate. Then there are ‘crowd crush’ tragedies, which happen when too many people are packed in a confined space, causing them to push and fall. This is different from stampedes, when there is space for those in a gathering to rush or run, typically to reach something or escape from somewhere.

Psychologists talk of a ‘trigger’ — some fear, anger or an external factor like an awareness of danger — that pushes a crowd to react.

"Once a trigger occurs, it rapidly escalates into mass panic, pushing people into a collective fight-or-flight response where rational thinking shuts down and the only instinct is self-preservation,” explains Vandana, clinical psychologist at Chennai-based V-Cope. “This is worsened by emotional contagion and the rapid spread of misinformation, such as false shouts of fire or collapse that fuels chaotic behaviour."

Also read: How residents of Udhampur’s Tirshi village have lived since losing homes in September landslide

The options to act on the instinct to self preservation, however, are not very readily available as many such gatherings offer limited exit or evacuation plans, despite anticipating a huge crowd.

"After the RCB won, I understood that the preparations for celebrations needed more time and as a layman, I felt the need for more time to prepare adequately. Henceforth, we should ensure adequate preparations and not just the passion for it," says Mamatha Maben, former captain of the India Women's Cricket Team.

RCB fans outside the Chinnawamy Stadium. PTI File Photo

What cricket writer Joseph Hoover would like to highlight is how avoidable this, and similar tragedies, could be.

"It was chaotic, they did not apply their mind. While the blame game continued for long, we need to understand that the RCB management and the management of the Karnataka State Cricket Association also have to be held responsible for the stampede,” he says. “The focus should be that this should never happen again and there should be a plan for such events.”

On January 16, RCB said that in a formal communication to The Karnataka State Cricket Association (KSCA), it has proposed the installation of 300 to 350 AI-enabled cameras at the M Chinnaswamy Stadium to enable law enforcement agencies to efficiently manage crowd movement, ensure disciplined queueing, monitor unauthorised access through real-time tracking of entries and exits, and significantly enhance overall fan safety.

Meanwhile, experts cite recurring systemic failures, including overburdened infrastructure, lax enforcement of capacity limits and a reactive rather than proactive approach to crowd dynamics, as reasons behind many of the stampedes in recent years.

Swami Jitendranand Saraswati, general secretary of Akhil Bhartiya Sant Samiti, who was present during the stampede at Prayagraj Mahakumbh, holds the administration accountable for the loss of lives. “The administration is often unable to assess the crowd and devotees suffer the consequences of this,” he says. Referring also to the Tirupati stampede, which had taken place just days earlier, he questions, “Is the administration unable to keep up with the growing devotion among the Hindus for their religion and culture? This is the fault of the authorities and administration?”

Amarnath Mishra, chief warden, Civil Defence, Lucknow and a crowd management expert, believes there were two flaws in arrangements which led to the stampede at the Prayagraj Maha Kumbh. "There was only a single route for the crowd to come and go at the Sangam area, which caused the crowd to cross each other. Also, the huge crowd on Mauni Amavasya was already anticipated. In such a situation, the holding area should have been separate.”

Mishra also calls for people and authorities to be more vigilant. "Most stampedes happen owing to our aggressive behaviour,” he insists.

Meanwhile, event planners like Chennai-based Showspace Events emphasize zoned entry systems and volunteer training for better crowd management.

According to CV Bhaskar, designated partner, Showspace Events LLP every large-scale event must begin with selecting the right venue and infrastructure. Planning should begin by mapping multiple entry and exit points, segregating celebrity routes to prevent queue-jumping, and managing one-way traffic flow during influx and dispersal.

"Separate entry and exit, along with 10–20 per cent extra capacity buffer, are critical. Technology now tracks real-time attendance; the moment numbers cross thresholds, organisers must immediately stop entry, divert crowds, or open emergency routes, even if it means overriding earlier restrictions. The venue should be divided into self-contained zones of 500–750 people each in case of bigger events and facilities such as toilets, water and refreshment points should be available, to ensure that overcrowding is easier to isolate and manage," says Bhaskar.

Stampede at the Sri Venkateswara Swamy Temple in Srikakulam. PTI File Photo

However, despite meticulous planning, incidents occur when turnout doubles unexpectedly or communication breaks down among multiple stakeholders.

Senior journalist Koteeswaran, who was present at the Karur rally when tragedy struck, describes stampedes as a global and endemic phenomenon, not exclusive to India or developing nations, but one that has repeatedly struck even developed countries. The root cause, he stresses, is a dangerous lack of understanding, civic sense, and awareness: a crowd of just 2,000–3,000 people can turn into a “time bomb” if basic etiquette — like maintaining queue discipline or giving neighbours elbow room — is absent.

"Despite annual tragedies and the existence of the 2005 Disaster Management Rules that classify stampedes as man-made disasters, policy-level changes remain absent," he rues.

Koteeswaran adds: "When we can impose regulations to control crowds as during the pandemic, we can enforce crowd-regulation discipline in such cases [events and public places] too. The disaster management regulations need to be implemented properly and there should be urgent, multi-level action, including strict central and state government policies on permissible crowd sizes, mandatory clearances scaled by expected attendance, such as district collectors for thousands, senior officers for tens of thousands, and standard operating procedures.”

Additionally, he also talks of the need to ensure proper fire safety measures, ambulances, toilets and drinking water facilities by organisers. “A dedicated nodal officer or separate government wing should monitor compliance and the government can charge a fee in such cases too, to ensure accountability,” says the journalist.

Poovulagin Nanbargal, an environmental organisation in Tamil Nadu, which studied the Karur stampede, highlighted how extreme heat stress among a dense crowd precipitates fatalities and chaos. The study analyzed thermal conditions via the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) and JOS3 thermophysiological modelling,to reveal lethal interactions between human, environmental, and infrastructural factors.

The study report stated that large gatherings generate intense heat through metabolic output from densely packed crowds when exceeding four people per square metre, releasing 200-1000 W/m² (watt per square metre) depending on activity level, comparable to midday solar radiation.

“This heat traps locally as bodies obstruct wind flow, block radiative cooling via reduced sky view, and limit conduction. Tamil Nadu is not ready to host events like these between April to October owing to environmental factors and even evenings can be difficult to bear. People might require one litre of water every hour to stay hydrated, but it's not feasible in large-scale events to cater to this need,” explains G Sundarrajan, environmentalist and Poovulagin Nanbargal coordinator.

The study stated that core body temperatures rise to 38–41 degrees Celsius within one to three hours in such situations, triggering fainting, dizziness, impaired judgment, and mob surges.

Also read: Why Delhi moms across economic and social groups are losing out to a common fear

In a similar incident in October 2024, five reportedly died from heatstroke and exhaustion and hundreds of people were hospitalised owing to overcrowding, poor planning, and inadequate public transport after an Indian Air Force (IAF) airshow at Marina Beach.

In June 2022, three people reportedly died in a stampede-like situation in extreme heat and humidity while attending a religious festival in West Bengal’s North 24-Paraganas district.

In Karur, the alleged delay in starting the event exposed 50,000 people to UTCI more than 38 degrees Celsius for more than six hours in narrow urban spaces, causing heatstroke deaths before the stampede, the Poovulagin Nanbargal study claimed.

In the aftermath, survivors often suffer severe post-traumatic stress disorder, recurring nightmares, profound survivor's guilt and deep depression marked by feelings of helplessness and worthlessness, requiring extensive time and professional support to overcome.

Looking back at the events of September 27 in Karur, Muthu (identified by a single name only), who runs a shop at the place where the rally had been organised, told The Federal, "We have no anger towards anyone. People have moved on because life goes on, but I don't think we can ever forget what happened that night. It won't be forgotten for many years from now on."