Alagirisami's short story 'Raja Vandhirukkirar' is part of Diwali lore for Tamil readers

The Tamil literary world has created profound works in poetry, and in essay and novel formats, which can easily win a Gnanapeeth or even the Nobel Prize.

Tamil literature had Pudumaipithan, who is considered as the Father of Tamil short stories and a non-pareil storyteller. His stories are classic and timeless. After Pudumaipithan, there have been many writers who carried forward his legacy – stories brimming with humaneness – and they carved a special place for short stories in the Tamil literary space. One such writer was Ku. Alagirisamy, whose birth centenary kicked off on September 23 this year.

In a life spanning 40 years, Alagirisamy has written more than hundred short stories, four novels, two children’s literary collections, nine translations, two plays and four essay collections. He was the first writer to translate the works of Russian writer, Maxim Gorky, in Tamil.

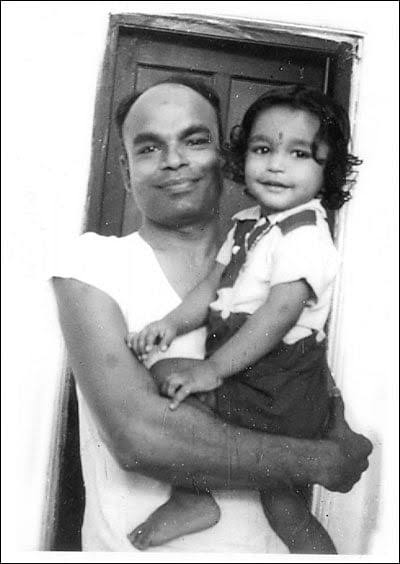

A father of four, he had written in his personal diary that he had taken a vow on the Tamil epic Kamba Ramayana not to beat his children even if they were mischievous. He deeply loved his children and maybe that is why most of his short stories revolve around children. For Maalan, a senior journalist and writer, Alagirisamy’s works deal with “child psychology”. Alagirisamy was awarded Sahitya Akademi posthumously in 1970 for his short story collection Anbalippu (The Gift).

Also read: ‘Homeless poet’ Francis Kiruba’s authentic voice in new-age Tamil literature

A gifted writer from Karisal

Tamil fiction continues to bloom in different landscapes like Kongu, where the agrarian society becomes a canvas; Nanjil Nadu, where the Pillai community form the backdrop for the stories; the banks of Cauvery, where the stories revolve around the Brahmin community, and then there’s Karisal, where the arid or semi-arid areas of Thoothukudi enter the stories as characters.

Alagirisamy forayed into writing from these parched lands. He was a contemporary of Ki Rajanarayanan, a forerunner of Karisal dialect literature. It was a watershed moment in Tamil literature, when Alagirisamy made his mark on the literary world dominated by Brahmin writers from Thanjavur. While the Thanjavur-based writers showed the lush green lands and a world annotated with Carnatic music from the Cauvery banks, Alagirisamy and Rajanarayanan portrayed the working class, who are mostly agrarian labourers.

Born to Gurusamy and Thayammal, Alagrisimy was able to complete only his SSLC due to his abject poverty. However, he was the only one in his village Idaiseval to have studied up to that level.

Though he hailed from a Telugu speaking family, Alagirisamy spoke Tamil outside his home. His debut short story Urakkam Kolluma was published in Anandha Bodhini magazine in 1943. After completing his education, he got a job as a clerk in a sub-registrar office for a salary of Rs 35. The amount he received would have been sufficient to run his family but still he found no pleasure in his work. Hence, he resigned and went to Chennai to take up a job as a journalist.

He first joined Anandha Bodhini magazine and later worked in magazines like Prasanda Vikatan, Tamil Mani and Sakthi. In 1952, he moved to Malaysia, where he joined the Tamil Nesan magazine. In Malaysia, he also found his partner Seethalakshmi, a singer.

Four years later, Alagirisamy returned to India along with his family and started working in the Navasakthi magazine. In the later part of his life, he did translations and wrote plays. In 1970, he passed away due to chronic bone tuberculosis.

Also read: World Book Day: Kalachuvadu makes its mark on Tamil literature

A story to remember every Diwali

A story to remember every Diwali

His short story Raja Vandhirukkirar (The King has come), is regarded as one of the finest short stories published in Tamil to date. Set in the backdrop of Diwali celebrations, the story talks about class inequality and divide and how children find happiness in small things during Diwali making the festival special in their lives. This particular short story is translated in many languages, including Russian.

Ramasamy, the second child of a landlord, is a class 5 student in a government school. Chellaiah is his classmate, who has a younger brother Thambaiah and a sister Mangamma. Ramasamy, always brags about his rich family and once challenges Chellaiah into a word game.

“I have a silk shirt. What do you have?” asks Ramasamy. To this, while Chellaiah fumbles for an answer that will equal a silk shirt, Mangamma counters him by pointing out that a silk shirt can tear soon but Chellaiah’s shirt has a longer life-span.

By portraying these petty skirmishes between children, Alagirisamy paints a working-class world. The story also weaves in how Chelliah’s father can only buy a towel as an upper garment for Diwali. Agrarian labourers at that time were not permitted to wear shirts or any other upper cloth except for a towel. And, when they came before a dominant caste person they had to take off the towel from their shoulders and tuck it under their armpits.

Alagirisamy’s forte lay in bringing out these nuances to the fore – the caste differences and discriminations practised at that time, in a subtle way.

Also read: Death of an ‘Adikavi’ and his influence on Tamil Dalit literature

A night before Diwali, the three siblings find a destitute child named Raja rummaging through waste food near a dustbin discarded by Ramasamy’s family. Overcome with pity, Chelliah’s mother Thayamma takes Raja into her home.

Next morning, on Diwali day, seeing Raja’s dishevelled condition with his skin covered with rashes, she tenderly bathes him and feeds him. While the three siblings had new dresses for Diwali, Raja had nothing. Thayamma, who had sacrificed her desire to buy a new saree for Diwali, so that her husband can get a towel for himself, now wonders what to do with the child. When tears fill her eyes, Mangamma asks her to give the towel, which was reserved for their Ayya (it is a practice that in the deep south of Tamil Nadu, children use to call their fathers as Ayya) to Raja. Moved by her empathy, Thayamma hands over the towel to Raja.

Ramasamy, clad in expensive clothes, tries to show off before the three siblings. His uncle, a zamindar’s son from a nearby village, is also visiting his house to celebrate Thala Deepavali (the first Diwali celebrated by grooms at the house of the bride after their marriage). It is a tradition to invite the groom to the bride’s house for Diwali celebrations. Zamindars were referred to as ‘Raja’ (The King) at that time.

The story ends with Ramasamy bragging that Raja is visiting his house for Diwali, only to be countered by Mangamma who cuts in to say, “Raja (referring to the destitute child) has come to our house too. If you want, you can come and see.”

The story narrated in a linear format without any big twists or turns vividly captures the innate empathetic qualities of children. It is for this reason the story was introduced as a lesson in Class 11 non-detailed portion under Tamil language paper in the 90s. It is not an exaggeration to say that the story has become synonymous with Diwali and part of its tradition for readers of Tamil literature. It is similar to how the song Ilamai Itho Itho (Sakalakala Vallavan 1982) became an iconic song for new year for movie goers.