BJP’s 'One India' vision is an obstacle for its success in state polls

The BJP is struggling to make a mark in state elections, as was evident in the latest results in West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, because of an inherent ideological flaw in its DNA.

The BJP is struggling to make a mark in state elections, as seen in the latest results in West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, because of an inherent ideological flaw in its DNA.

The Sangh Parivar visualisation that attempts to steamroll the mind-boggling diversity of the nation into one concise formulation has sparked resistance to its electoral ambitions.

The excessively-centralised leadership of the BJP is simply unable to come to terms with the fact that each state in the Indian union is a full-fledged nationality.

The extent of the real difference and separateness of each state encapsulated in the description “unity in diversity” can only be fathomed when say, a Kannadiga goes to Assam or a Marathi-speaker goes to Kerala. It is the equivalent of travelling to a foreign land.

In general, the lived experience of people who move from one state to another and the struggle to adapt to a new language, culture, cuisine and everything else is something that the BJP and its mentor, the RSS, is constantly in denial.

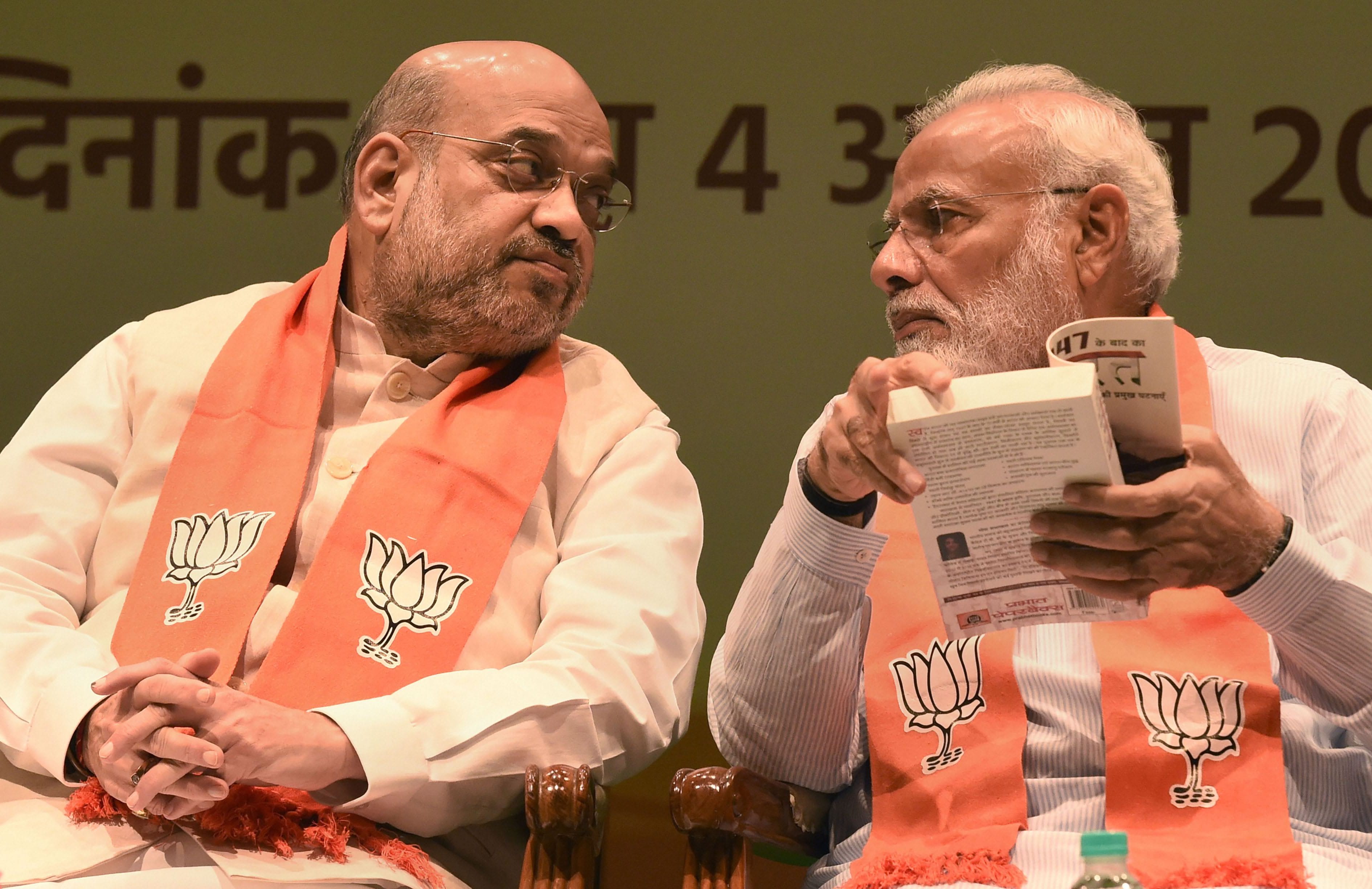

And this reflects in the BJP-led Modi government’s exhortation of “One India this, One India that…”. The most visible of this is the periodic and almost subversive thrust to establish Hindi as the dominant language across the various states. Home Minister Amit Shah has been the most brazen calling for it to be the “national” language. Many, in fact, wrongly believe Hindi is the “national” language when in reality it is an official language along with English as the link language.

The mindset of the BJP shows up in the singular attempt of the Modi government to undermine constitutionally-guaranteed federalism and convert the nation into a de facto unitary state. Take the amended farm laws, for instance (essentially a state subject) or for that matter, the centralised GST system that has ended up depriving states of much-needed funds.

The party is not able to absorb the fact that unbridled centralisation triggers enormous resentment in various states, which was particularly in focus in the current round of elections.

The BJP’s view of India’s oneness is made worse through a policy of communal polarisation which is now regarded as a key driver of its success. In a rather simplistic assessment, the BJP calculates that if all Hindus vote for it that would make the party unbeatable as the Hindu population in the country is around 80 percent. And, the only way to arouse an individual’s “Hindu-ness” is to make it appear as if the religion is in danger and then look for an enemy outside of it, in Islam or Christianity.

While there is no doubt that the BJP has succeeded in this Machiavellian enterprise in Lok Sabha polls, the results of the state elections have consistently shown it does not work beyond a point. As election strategist Prashant Kishor pointed out in a television interview on Sunday, based on the election results one can say such polarisation can work in half of the Hindu population but no more than that. The rest don’t buy it.

Also, a policy that works at the national level has few takers locally. It has been proven time and again that people think differently when it comes to Lok Sabha and state Assembly elections. Analysts on Sunday consistently compared the current results in West Bengal to the 2019 Lok Sabha elections when the BJP did very well across various Assembly segments. The comparison should have been only with the 2016 Assembly elections as the commonsense dictum is to “compare like with like”. Assembly segments in a Lok Sabha election simply do not matter, and it is a widespread fallacy to use data from that to understand how such Assembly constituencies voted in state elections.

The BJP was probably high on confidence in West Bengal as it did exceedingly well in the Lok Sabha elections in the state and went all out to seize the initiative. Though it did well by increasing its tally from three Assembly seats to around 80, that was not enough for it to replace Mamata Banerjee’s TMC.

Also read: BJP gains foothold in TN after 20 years, but sees drop in vote share

The notion of a nation, while valid, is ephemeral in the sense that people vote for a government in “distant Delhi”, on criteria that are in many ways different from that in a state. For the BJP at the central level, the ideas of national security, strong leadership and as a party that unabashedly represents the majority Hindu community have found takers across the country. But attempting to replicate something similar at a state level has boomeranged, save for some exceptions like Assam.

Token attempts like speaking a few sentences in the local language at public rallies cannot fool people into thinking that they are “one of us”. On the contrary, it has often times turned powerful politicians including the prime minister into figures of mirth. There are many of these clips doing the rounds on social media including one where Modi is struggling to verbalise high-flown Tamil.

Also read: Mamata’s win shows liberals antidote to BJP’s Hindutva poison

What is probably another structural limitation for the BJP is the fact that state level units too are forced to fall in line with the party’s centralised thinking and have been unable to connect with local communities. For example, in Tamil Nadu, the BJP is largely seen as a north Indian party, pro-Hindi and representing the upper castes. The validity of such a perception can be questioned, but none can deny that in reality such a view exists across large sections of the electorate.

In the campaigning during the recent elections, the BJP in Tamil Nadu tried to bring in the Ayodhya issue and when that failed tried to rake up a controversy over the popularly-followed local god Murugan. As the results showed, it cut little ice with the voters.

Regional parties like the TMC, or the DMK do not peddle politics for its own sake but are entities that have emerged organically from the ground up, fully in sync with local ethos, something that voters can easily identify with.

For the BJP to dethrone such parties it will have to necessarily acknowledge subaltern cultures, drop the “one size fits all” mindset and work towards a genuine federation. This is easier said than done. For, if the BJP does indeed incorporate these elements that may not go down well with the umbrella saffron parivar.