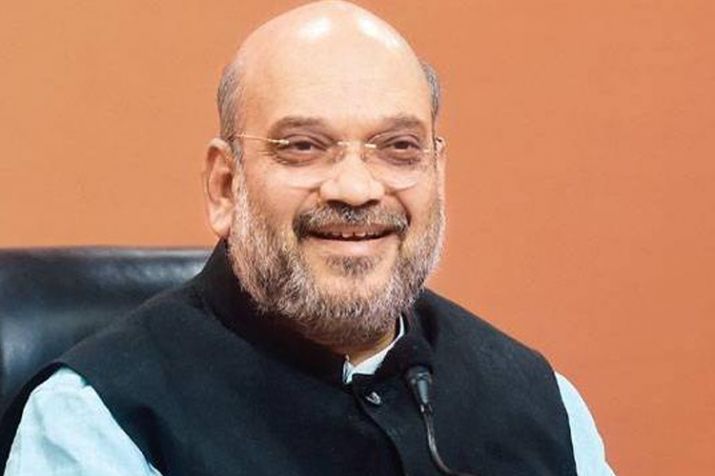

In Amit Shah’s Partition story, fantasy as fact, villains as heroes

Union Home Minister Amit Shah treats history the way David Beckham used to treat football once — he bends it the way he wants, in the direction he likes, and his fans go ga-ga over it with joy. But, the problem with bending it like Shah is that sometimes the home minister puts the ball in his own goal. Like he did in Parliament on Monday while blaming Congress for the Partition and defending the controversial Citizen (Amendment) Bill.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah treats history the way David Beckham used to treat football once — he bends it the way he wants, in the direction he likes, and his fans go ga-ga over it with joy. But, the problem with bending it like Shah is that sometimes the home minister puts the ball in his own goal. Like he did in Parliament on Monday while blaming Congress for the Partition and defending the controversial Citizen (Amendment) Bill.

“The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill wouldn’t have been needed if the Congress had not allowed partition on basis of religion. It was the Congress that divided the country on religious lines, not us,” Amit Shah said in the Lok Sabha.

There are so many holes in Shah’s arguments that you can literally fly a whole squadron through them.

Also read: Shah undeterred by protests, to push Citizenship bill in Lok Sabha

India and Partition

On June 3, 1947 Indians gathered around their radio sets for an announcement that was to change the destiny of the subcontinent. Around 7 pm, as Lord Mountbatten, Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Baldev Singh spoke one after another from the Delhi studio of All India Radio, it became clear to millions of people that their country will be partitioned. A few days later, Mountbatten, the last viceroy of India, announced from the Darbar Hall of his residence that the British would handover India to the Congress, and a new country called Pakistan to the Muslim League.

Contrary to Shah’s rendition of history, the Congress did not decide to divide India. Pakistan came into existence in spite of vehement opposition to it by the Congress. But, in the end, the Congress was handed over a fait accompli.

In 1946, the British sent a Cabinet Mission to India for handing over power. It came up with two separate proposals. The Mission proposed May 16 that India be governed by a weak Centre that would control only defence and foreign policy. The rest of the country was to be divided into Hindu and Muslim majority provinces under separate governments, led by the Congress and the Muslim League.

Also read: Lok Sabha passes Citizenship Amendment Bill after heated debate

In its 24 May resolution, the Congress responded to this by saying: “…They (Congress leaders) have examined it with every desire to find a way for a peaceful and cooperative transfer of power and the establishment of a free and independent India. Such an India must necessarily have a strong central authority capable of representing the nation with power and dignity in the counsels of the world.”

The British then came up with another plan in June. This time they proposed partition of India between Hindu and Muslim majority areas. The Congress rejected this in its resolution a few days later.

“In the formation of a Provisional or other governance, Congressmen can never give up the national character of Congress, or accept an artificial and unjust parity, or agree to a veto of a communal group. The Committee are unable to accept the proposals for formation of an Interim Government as contained in the statement of June 16. The Committee have, however, decided that the Congress should join the proposed Constituent Assembly with a view to framing the Constitution of a free, united and democratic India.”

Clearly, the Congress wanted a united India with a strong government at the Centre.

Also read: Federal US body seeks sanctions against Shah if Parliament clears CAB

Jinnah’s politics, Patel’s pragmatism

But, Jinnah was adamant on having his own country for Muslims. In August 1946, he called for ‘direct action’ in support of the Muslim demand for Pakistan. In the violence that ensued at least 4000 people died in Bengal alone.

According to Louis Mountbatten, the last viceroy of India, by April 1947 it was clear that partition was the only option to assuage Jinnah. In his personal report on April 17, 1947, Mountbatten observed: “He (Jinnah) has made it abundantly clear that the Muslim League will not reconsider the Cabinet Mission plan, and he is intent on having his Pakistan.” (Mountbatten and the Partition of India: Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre).

Sardar Patel was among the first to realise the Congress had run out of options. He feared the British would leave abruptly after handing over power to the Muslim League and this would lead to several divisions of the country. At a Congress working committee meeting to discuss the British Mission’s plan, he said:

“I fully appreciate the fears of our brothers from [the Muslim-majority areas]. Nobody likes the division of India and my heart is heavy. But the choice is between one division and many divisions. We must face facts. We cannot give way to emotionalism and sentimentality. The Working Committee has not acted out of fear. But I am afraid of one thing, that all our toil and hard work of these many years might go waste or prove unfruitful. My nine months in office has completely disillusioned me regarding the supposed merits of the Cabinet Mission Plan. Except for a few honourable exceptions, Muslim officials from the top down to the chaprasis, (peons or servants) are working for the League. The communal veto given to the League in the Mission Plan would have blocked India’s progress at every stage. Whether we like it or not, de facto Pakistan already exists in the Punjab and Bengal. Under the circumstances, I would prefer a de jure Pakistan, which may make the League more responsible. Freedom is coming. We have 75 to 80 percent of India, which we can make strong with our own genius. The League can develop the rest of the country…” (The Transfer of Power in India: VP Menon).

Also read: Citizenship bill represents India’s ethos of assimilation, tweets PM Modi

Sangh and Partition

One of the first proponents of the two-nation theory was Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, the ideological deity of the Hindutva brigade and the BJP. Much before Jinnah became adamant on India’s partition on religious lines, Savarkar had floated the two-nation theory. In 1937, as president of the Hindu Mahasabha, Savarkar claimed “there are two antagonistic nations living side by side in India. Several infantile politicians commit the serious mistake in supposing that India is already welded into a harmonious nation…On the contrary, there are two nations in the main: the Hindus and the Muslims, in India.”

A few years later, after Jinnah had hijacked the two-nation theory, Savarkar expressed his approval thus: “I have no quarrel with Jinnah. We, Hindus, are a nation ourselves and it is a historical fact that Hindus and Muslims are two nations.”

His colleague, Syama Prasad Mukherjee, was so keen on a divided Bengal that he argued in a letter to Mountbatten that even if the British do not divide India, they should create two Bengals—one for Hindus and the other for Muslims. Some historians argue in 1947, Mukherjee opposed efforts by Sarat Bose and Hussain Suhrawardy to counter Jinnah’s plan and keep Bengal united.

Compare this with the stand taken by Mahatma Gandhi, who opposed partition till the very end. Or, the vehement appeals by Nehru for keeping India united.

The truth about Partition

Poet-cum-politician Muhammad Iqbal was among the first proponents of the idea of Pakistan. He was convinced that Muslims would not be safe in a Hindu-majority India once the British left. Savarkar and his Hindu Mahasabha were of the same opinion, but for a different reason—they wanted Hindus to have their own separate land.

During the second World War, most of the Congress leadership was jailed by the British. In the vacuum their exit created, the Muslim League made deep inroads among the Muslims and managed to create the impression that the Congress is a party of the Hindus.

As a result, in the elections for the provinces and the centre, the League won most of the seats reserved for Muslims. This was seen by the British as a referendum on a separate state for Indian minorities.

The Congress fought till the very end for a united India. In 1946, speaking in front of a large crowd at Sukkur in Sindh, Nehru implored people to vote against the Muslim League, and, thus against India’s division. In front of more than 50,000 people, Nehru said in the free India, everybody would be provided with sufficient food, education and all the facilities including a house. He discarded Pakistan as a ‘useless India’ which only meant ‘slavery forever.’

In the end, results of the 1946 elections, violence on the direct action day called by Jinnah, the Muslim League’s insistence on a separate country for Muslims, and the Hindu Mahasabha’s support to the division of India, forced the Congress to accept the British plan for Partition.

In Shah’s version of the Partition story, you will, of course, hear fiction being passed around as history.