Delimitation and what it means for the people of Jammu and Kashmir

The Delimitation Commission was set up last year to redraw the electoral boundaries of Jammu and Kashmir and four northeastern states – Assam, Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland. The commission was given a one-year extension – only specific to J&K – in March this year

The restoration of the political process in the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir now awaits the delimitation exercise, which is expected to be completed by the end of this year. That means elections to the truncated assembly could happen sometime early next year.

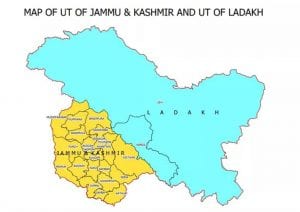

Following the revocation of article 370 and 35(A) in August 2019, the state was downsized into two union territories — J&K and Ladakh. A delimitation commission was set up with a mandate to carve out assembly and parliamentary constituencies.

The indications of a revival of the political process came with Prime Minister Narendra Modi holding a meeting with 14 top political leaders from the state in New Delhi on June 24. After the meeting, Modi tweeted: “Our priority is to strengthen grassroots democracy in J&K. Delimitation has to happen at a quick pace so that polls can happen and J&K gets an elected government that gives strength to J&K’s development trajectory.”

Delimitation & the debate

The current Delimitation Commission is the fifth since Independence. It is unique in the sense that it was formed when there was a constitutional freeze on the increase or decrease of the parliamentary and legislative assembly seats till after the 2026 census.

Also read: Centre’s call for dialogue: J&K parties tread with hope, and caution

Delimitation is the process of redrawing boundaries of parliamentary or assembly constituencies to reflect changes in population over time. Carried out after every census, it is meant to ensure that the ratio between the seats in the assembly/parliament and population remains the same.

In the case of J&K, the commission, though set up under the Delimitation Act of 2002, will redraw the constituencies in accordance with the provisions of the J&K Reorganisation Act, 2019. This, according to critics, compromises the commission’s mandate vis-a-vis J&K.

As per the J&K Reorganisation Act, the number of voters has already been decided by stipulating the population census of 2011 as the base. For all other states, including the four – Assam, Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland – going in for delimitation along with J&K, the population figures of the 2001 census are being used.

Through the Act, the Centre has raised the number of representatives to the legislative assembly of J&K from 107 to 114. So far, changing the number of representatives has been the prerogative of the Delimitation Commission. It is empowered by Clause 8(B) of the Delimitation Act of 2002 to decide on “the total number of seats to be assigned to the Legislative Assembly of each state and determine on the basis of the census figures”.

Since the number of voters and the number of elected representatives is prefixed (Census 2011), the panel has been left to decide on the electoral cartography — the redrawing of boundaries and binding people within a constituency framework. This runs the risk of potentially changing the electoral demographic balance.

Today, the Kashmir division has 56 per cent of the UT’s population, while Jammu has 44 per cent. However, the landmass or the area of Jammu division is now 62 per cent, while that of Kashmir is 38 per cent. This is the reason for a clamour from Jammu-centric political parties and civil society for using area as a criterion for delimitation. The Kashmir valley has a majority Muslim population.

On the basis of topography, J&K comprises four distinct regions — Jhelum Valley (south Kashmir, central Kashmir and north Kashmir), Chenab Valley (Kishtwar, Doda, Ramban and Reasi), Pir Panjal (Rajouri and Poonch), and the Tawi Basin, or the plains (Jammu, Kathua and Udhampur).

The case in Supreme Court

The proceedings of the Delimitation Commission, which has five MPs (three from the National Conference and two from the BJP) from the erstwhile state of J&K as ex-officio members, have been boycotted by the NC, though there has been a rethink within the party.

Before Parliament passed the Reorganisation Act in August 2019, the effective strength of the assembly was 87, including four seats from Ladakh, which is now a separate Union Territory without a legislature. The strength of the realigned Jammu and Kashmir assembly is now 114 – 24 seats will continue to remain vacant as these are in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

Also read: First delimitation, then elections: PM to J&K leaders after three-hour meet

The NC members, while disassociating themselves from the Delimitation Commission, have said the party has challenged the Act in the Supreme Court and the matter is pending.

The apex court now has to examine whether the Union government can “unilaterally unravel the unique federal scheme under the cover of President’s Rule while undermining crucial elements of due process and rule of law.”

After the meeting with the PM Omar Abdullah of the National Conference questioned why Jammu and Kashmir has been singled out for delimitation. After the 2001 census, the assembly had passed a law putting off the process till 2026.

“We said delimitation was not needed. If August 5 was to unite the state with India, then the delimitation process defeats the purpose as we are being singled out,” Abdullah said. “If the Delimitation Commission could be withheld and assembly polls held there, then why not for Jammu and Kashmir?” he asked.