Are women’s posteriors fetishised, objectified in our culture? Butt of course

In our bodies, we carry histories. This is the conclusion American essayist Heather Radke arrives at in her new book, Butts: A Backstory (Simon & Schuster), a work of cultural history that traces the anatomical and physiological thought and meaning associated with the behind, especially women’s posteriors.

Drawing on her own experience with her body, Radke dissects how butts became the basis of our most vulnerable feelings, weaving in threads about desire, shame and power. She also analyses how butts, often a measure of sexual desire and availability, create and reinforce racial hierarchies.

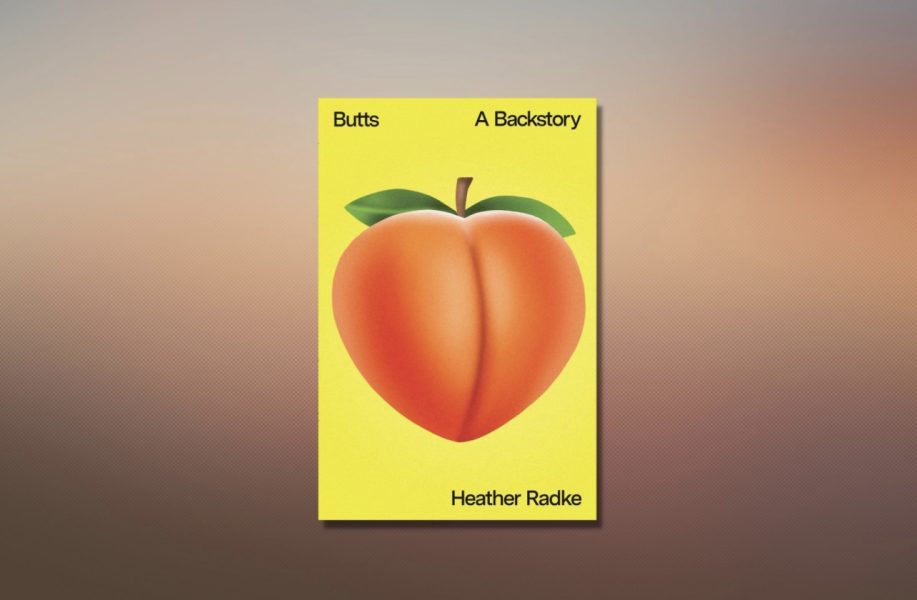

Variously referred to as ‘behind, backside, posterior, rear end and bottom’, the fatty and fleshy part of our body is represented by the peach emoji on the book’s cover. Delving into the historical starting points of butt, Radke explores how its perception has evolved — ever since the first known hominid with a butt was found near the arid shores of Kenya’s Lake Turkana 1.9 million years ago — and continues to resonate in the present. In the last 30 years, the public attitude towards women’s butt has changed drastically as evident in the fascination and obsession with the behinds of women like Kim Kardashian and Jennifer Lopez.

Examining levers of power

Radke, who also dwells on the fitness trends, writes in the introduction to the book that she is primarily interested in butts as construed and represented by mainstream, hegemonic Western culture — “the culture of those who hold political and economic power, those who dominate popular media and who are most responsible for creating, perpetuating, and enforcing broad standards and trends.” Even as she articulates the personal — her own experiences and feelings — she makes it clear that the book is also a political project, a way of “teasing out and examining levers of power that aren’t always visible”.

Also read: Shah Rukh Khan, women, Indian economy, and a book that links these

The book investigates butt’s history through the eyes of butt experts of all hues, from historians, scientists and archivists to drag queens, dance instructors and non-binary people. Radke probes them on what butts mean to them and as she does so, she tells us stories steeped in tragedy, anger, oppression, lust, and joy — surprising us, as she herself had been while writing the book, how many different meanings one body part can contain, and the shades of ideas and prejudices it engenders: some of the insults hurled at women include butthead or buttface. If sexual harassment in public places and catcalls centre on women’s butt, it is also vital for validation and key to flirtation: If you are told that you are a callipygian (Greek word), it means you have beautiful buttocks.

Casting a wide net

The story of Sarah Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman belonging to the nomadic pastoralists of South Africa, who was exhibited as a freak show attraction in 19th-century Europe under the name ‘Venus Hottentot,’ serves as the historical starting point for Radke’s framework. “Her cruel and lurid display in life and death is foundational to perceptions of the butt for the past two centuries,” writes Radke, who goes on to cast a wide net, peering into the histories of as varied subjects as fashion, race, science, fitness, and popular culture. She also writes about a procession of people who have shaped ideas about butts, including a model, an illustrator, a eugenicist artist and a fat fitness instructor into aerobics.

The first hominid with a butt, discovered in the African savanna, had “a protruding gluteal muscle at the top of each hip, the underlying flesh of a round, strong backside.” It was several millennia later, in 1974, that Bernard Ngeneo, who was part of Kenyan palaeontologist Richard Leakey’s ‘Hominid Gang, stumbled upon the evidence of an entirely new species in the family of Homo Sapiens — the species to which all modern human beings belong — not too far from Lake Turkana. Ngeneo’s discovery of the fossil, KNM-ER 3228 gave science a critical tool for understanding the purpose and evolutionary backstory of the human butt. About two million years ago, Homo erectus, the first human ancestor to walk around on two legs, first came on the scene.

Radke writes how butts are crucial in keeping us humans from tumbling forward as we launch ourselves off our back feet when we run; they help us run for long distances, without injury. In women, they acquire a physiological significance. Since women bear the primary biological burden (reproduction), they need to have enough muscle and fat reserves during pregnancy and breastfeeding. This reserve inevitably gathers in hips, butts and breasts.

Racial hierarchies and stereotypes

After colonial exploration in Africa in the late 19th century, European explorers and scientists began to employ “pseudoscientific theories” about big-butted Black women to construct and reinforce racial hierarchies and stereotypes, particularly that of the hypersexual Black woman. Baartman’s story became central to new histories of science, race, and the African diaspora in the 1990s, primarily due to the work of scholars like Sander Gilman and artists like Elizabeth Alexander and Suzan-Lori Parks. Radke tells us how Baartman’s name came to be associated with a Victorian undergarment, the bustle. As the false butt, designed to make a woman’s backside look enormous through an accordion-like cage or puffy pillow tied to the waist, came to define the female silhouette of the late nineteenth century, some cultural historians argued that it was inspired by Baartman, even as others vehemently denied it.

Podcast: Women need better, greater representation in films: Sowmya Rajendran

It was the fitness phenomenon of the 1980s and the 1990s, Buns of Steel — based on fitness entrepreneur Greg Smithey’s workout regime — that marked a major shift in expectations about bodies should look like; spoofed on Saturday Night Live, the bestselling VHS exercise tape was purchased by people all over the world who actually wanted to have ‘metal-hard buns’ — an idea that was at once alluring and ridiculous. At a time when America was preoccupied with the gospels of entrepreneurship and self-creation, the success of the fitness programme had to do with the fact that it exploited a popular connotation around butt: To be a “hard-ass” is to be tough and uncompromising.

A transformative experience

A few years later, in 1998, mainstream America discovered Jennifer Lopez’s butt; Lopez had started her career in 1991, but after the release of Selena (1997) — in which she plays a Tejano superstar, Selena Quintanilla, in all her curvy glory — her body became representative of an ideal that many saw as emblematic of femininity in Latin and South America, Radke writes. Similarly, Beyoncé Knowles’ 2001 Destiny’s Child hit “Bootylicious” gave rise to the general enthusiasm for curves. Today, it can be seen as a body-positive feminist anthem. Miley Cyrus’s 2014 performance (twerking), became one of the most-talked-about butt-related moments in the history of popular culture.

Radke does something quite radical with the book. She shows how an examination of a part of ourselves — body parts, emotions or desires — that can feel unbearable or traumatic can also be transformative. “By growing curious about the sources of shame and by putting that shame in context, we don’t excuse ourselves, or even get beyond it. Instead, we turn toward rather than away, a gesture that allows for new possibilities and knowledge,” she concludes.