- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Ye Haa... How Badaga folk music stayed in tune with times

The word music to ordinary Indian ears is largely about film scores. Other genres need specific prefixes such as ‘folk’, ‘classical’, ‘pop’, ‘indie’ or ‘Carnatic’. While classical and pop do get their due in popular media, folk or indigenous music rarely gets the attention, unless the film industry embraces it. Folk or indigenous music...

The word music to ordinary Indian ears is largely about film scores. Other genres need specific prefixes such as ‘folk’, ‘classical’, ‘pop’, ‘indie’ or ‘Carnatic’.

While classical and pop do get their due in popular media, folk or indigenous music rarely gets the attention, unless the film industry embraces it.

Folk or indigenous music forms generally use their own, self-made musical instruments, mostly made of natural material such as wood, climbers, bones of dead animals, etc. And indigenous music used only on occasions like festivals or deaths have even a much more limited audience. Such music is not meant for casual entertainment. Due to this, they are unable to travel outside a particular ethnic group or even find appreciation among the youths.

Film scores, on the other hand, have a huge impact and reach. So much so that certain indigenous musical forms such as ‘dappankuthu’ became mainstream after cinema embraced it.

Most music directors in the film industry used a mix of traditional and modern instruments and technologies to make indigenous music palatable to a larger audience.

Some from ethnic groups have found in this feature a new calling and a chance to take their music to a wider audience.

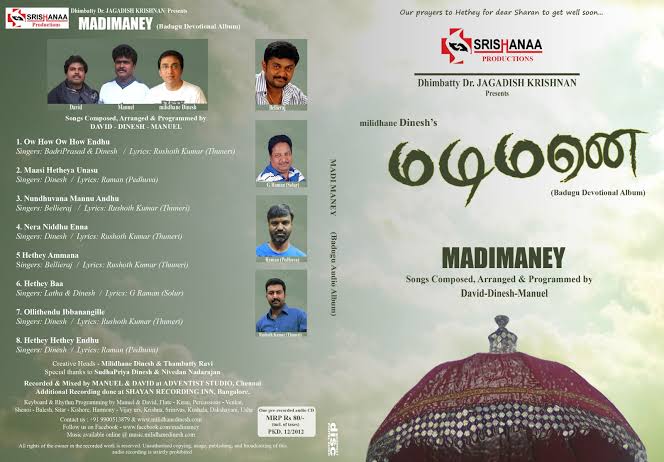

One such ethnic group is the Badagas, who embraced ‘filmy’ elements into their musical form about 20 years ago. Since then it has travelled a long way and has become a sought-after entertainment element in the lives of Badagas who have migrated from the forests to cities.

Badaga – a language sans script

Badagas, though not a Scheduled Tribe according to the government or foreign historians, are an indigenous people living in the Nilgiris hills in the Western Ghats. They have a unique culture and language but are one of the least studied ethnic groups as compared to other indigenous people of the hills such as Todas.

The Badagas language resembles Kannada in speech but lacks script. Their culture too has more similarities with Kannadigas. Since they opted to stay in Tamil Nadu, they embraced Tamil as their mother tongue.

Though most Badagas use Tamil language for writing, there are attempts made by some to popularise Badaga language using the Tamil script. They used to publish posters and invitations of temple festivals, marriages in Badaga using Tamil letters. They even brought out a Badaga edition of the Bible titled ‘Gavatha Suddhi’.

In recent times, some of the self-taught linguistic researchers are in the process of developing new scripts for the language. However, in 2012, Christiane Pilot-Raichoor, a French linguistic scholar of Langues et Civilisations a Tradition Orale (LACITO), a branch of Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), has claimed that Badaga, a Dravidian language though widely believed as a dialect of Kannada, is a separate language.

Transformation in music

According to researchers, Badaga ancestors understood the importance of music and they developed a simple jingle or beat ‘Ye Haa How… Ye Haa How’, which is used during marriages and funerals. This simple beat became the base for later compositions of lengthy songs.

Earlier, Badaga songs were sung on Gods and were sung only in temples and termed as ‘Bhajanai’ (Bhajans) songs. Later, when the changeover happened, songwriters started penning songs on pride of their villages, love and relationships and even added a tinge of modernity in ‘Bhajanai’ songs.

Initially, Badaga audio cassettes were created for the Badagas who lived outside their villages. Early songs such as ‘Nilagiri Nakkubetta’ (1989), ‘Nethiya Barey’ (1993), ‘Singara Seemey’ evoked old memories of villages, clans among the Badaga diaspora, and helped them maintain ties with their community and culture.

It is said that L Krishnan of Thangadu village was one of the pioneers in Badaga bhajans and used to sing at temple festivals. He was so popular that people used to record his songs while he was singing and play it in other temple festivals which he was unable to attend.

Later, G Raman from Sholur village took an initiative to create the first Badaga album on an audio cassette. Along with M Krishnan from Nundhala village, he penned songs with modern themes that were received well among the community.

Besides individuals, organisations like Karnataka Badaga Gowdas Association (KBGA), an early association of Badagas in Bengaluru, also began bringing out Badaga albums. It was KBGA which released the first professionally made Badaga album. The songs were composed by Chakravarthi, a leading Telugu film musician in the 80s.

“In those days, the individuals didn’t have the means and ways to bring out their songs in an audio format. We wrote songs that were mainly used in skit and enacted by the college students. It was in one such skit ‘Sathiya Vaakku’ that I wrote a song ‘Athimora mele onthu annakili’. The song and the skit bagged first prize in the drama competition held in 1981. But I had to wait for another 15 years for the song to reach the people through an album format,” says Solur G Raman, a well-known lyricist and singer in Badaga.

Apart from ‘Athimora mele’, songs like ‘Betta naakka suthiya’, ‘Mele Keriyogey’, ‘Aana moganey ninna’, ‘Manaiye maradhothu Muruga’ and, ‘Haa akka’ became popular numbers. The song ‘Mele Keriyogey’ is particularly played repeatedly with dance performances during college festivals.

Raman recalls that in the 80s, the cost of recording was so high that they once recorded 19 songs within five hours with limited artistes.

“The first album in Badaga had no title, because we had no idea about those things at that time. We brought just 65 audio cassettes for that album. But when the songs got a good response, people recorded them from one cassette to another and sold it in thousands,” he says, adding that the most sold Badaga album till date is ‘Singara Seemey’ with 12,000 cassettes.

The SPB moment

The pioneers of this initiative proved to their own community that they can compose ‘filmy’ songs and produce albums. But how to make it popular?

‘Milidhane’ Ravi Viswanathan arrived on the scene at this moment and made Badaga songs more filmy, by using playback singers.

A self-taught musician, Viswanathan had worked in then Cheran Transport Corporation for 10 years, but quit it and joined the film industry in Chennai. Having worked as a keyboard player with popular musicians like Deva, Gangai Amaran, Viswanathan brought refreshing beats to Badaga songs and to date, has composed nearly 50 Badaga albums and about 500 songs.

It was with his collaboration that SP Balasubrahmanyam sang popular numbers such as ‘Oh mamma aadabaari aattaa’ and ‘Habba jina aadothega aaduvo’.

“Every other language having a script started entering the film industry, striving to make a mark. They were received well by their audience. We too thought that Badaga songs should travel out of our community. We believed that if we have some popular film playback singers give their voice for our language, we could get more audience from non-Badagas. And SPB played an important role in this effort,” he says.

SP Balasubrahmanyam, who was recently awarded Padma Vibhushan, has highly spoken about the Badaga language whenever he got an opportunity either during his live performances or on TV shows. That helped turn people’s attention towards the Badaga language, culture and people.

This could have given a push for singers like Belliraj (who sung ‘Kangal irandaal’ in the film ‘Subramaniyapuram’), actors like Sai Pallavi, Vani Bhojan (who acted in serials like ‘Deivamagal’ and films like ‘Oh My Kadavuley’) and makers like Karthick Naren (director of films like ‘Dhuruvangal Padhinaaru’ and ‘Mafia’) to make an effort in the Tamil film industry.

“The attempts made by singers like Solur Raman were mainly based on harmonium. That was the only instrument used commonly but is sweet to hear even to this day. But I wanted to go the extra mile. I wanted to create Badaga songs in a cine music style with different instruments. The album ‘Nethiya Barey’ was the first Badaga commercial album in the truest sense and SPB sung his first Badaga song in that album,” says Viswanathan.

“SPB has sung six Badaga songs in total. Whenever I went to him requesting his call sheets, he always gave first preference to us. He loved the language and had huge respect. He always wanted us to take the songs to be remade in other languages too,” he says.

Besides SPB, Viswanathan also roped in other playback singers like TM Soundarrajan, S Janaki, P Susheela, Sujatha, KS Chitra and Mano to sing Badaga songs.

Cassettes to social media

According to Raman, the last Badaga album in an audio cassette form was released in 2017.

“After cassettes, many youngsters brought audio CDs. From 1987 to till date nearly 1,500 Badaga albums could have come and gone without a trace. Only a few albums make a mark. Today, youngsters are focussing more on single video romantic songs and uploading it on social media. For cinematography, editing, recording it costs at least ₹20,000. In those days, if we had that amount we could have produced an audio cassette having eight songs” says Raman, adding that the youngsters should listen to the older songs and build their vocabulary.

Concurring with him, Viswanathan says that while youngsters are focusing more on duet songs, people like him are in the process of preserving traditional songs.

“Every Badaga village in Nilgiris has at least 100 songs in different genres such as love, sad, wailing, devotional, etc. The elders in each household has a story to tell in the form of a song. We need to preserve them in order to protect the language and the culture of this land” Viswanathan says.