- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

The 'no land's men' in Munnar's tea estates

With each passing day, Chinnathai — a third-generation tea plantation worker of Tamil origin in Munnar — is reminded of her approaching retirement in two months. And with that, the fear of becoming homeless.

Life in the labour lines in idyllic Munnar offers a shocking contrast to the beauty of the unending hill slopes shrouded by green carpets of tea bushes. Yet, for Chinnathai, a tea plantation worker, her leaky, worn down house is her most prized possession. Leaning against the wall of her house, the 58-year-old looks increasingly worried, as the sun sets behind the lush green hills....

Life in the labour lines in idyllic Munnar offers a shocking contrast to the beauty of the unending hill slopes shrouded by green carpets of tea bushes. Yet, for Chinnathai, a tea plantation worker, her leaky, worn down house is her most prized possession.

Leaning against the wall of her house, the 58-year-old looks increasingly worried, as the sun sets behind the lush green hills. “One more day gone,” she says. With each passing day, Chinnathai — a third-generation tea plantation worker of Tamil origin — is reminded of her approaching retirement in two months. And with that, the fear of becoming homeless.

“My grandparents migrated from a village in Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu to Munnar about seven decades ago to work in the tea estates here. Like them, we continued to work and live here,” she says.

Chinnathai, like many others of her time, has been living in the decrepit residential quarters for generations. The company they and their forefathers worked for — the Kanan Devan Hills Plantations (KDHP) — had provided those on its rolls with small shanties. Most of those living in the now-concrete labour quarters have no land or home of their own.

“Since we continued to work in the tea estate, we have been residing in the same house for generations,” says Chinnathai.

But now, with her only son, a BSc graduate working outside Munnar, Chinnathai will have to vacate the house after retirement.

“We do not want to force our son to toil in the tea estate like us for meagre wages. But, if none of our family members works in the tea estate, we cannot live in this house provided by the estate management,” Chinnathai laments.

A long walk from home

Most tea workers in Munnar are descendants of the labourers brought from Tamil Nadu by the British way back in the 19th century to work in the early plantations at Munnar. According to historian and writer Ira Murugavel, hundreds of poor and oppressed people from Tamil Nadu went to these estates to work. While most of them belong to Scheduled Caste communities from Tamil Nadu, only a small number of the estate workforce are locals from Kerala.

With time and education, more and more people over the years have started working outside the estates for better-paying jobs. However, many, especially the women, are forced to stay in their tea plantation jobs mainly to retain the quarters.

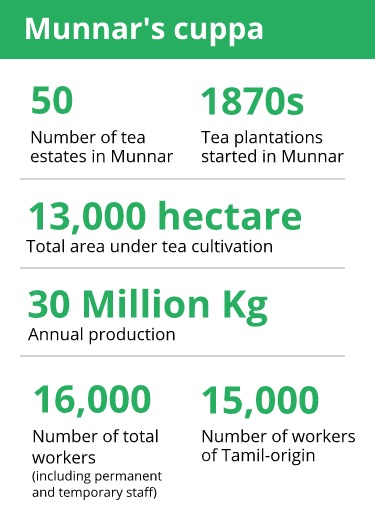

As a result, nearly 15,000 workers now find themselves in a fix as their children are no longer interested in toiling in the tea gardens, plucking leaves, trudging up and down steep slopes with heavy baskets, braving the sun and rain, wild animals and a wilder fate.

“Although the conditions are much better than when we started working, I knew it would be hard for my son to work in the estate after completing school (Class 12). But, we do not have any other option. He has to work in the tea garden to retain the house,” says Pachchamuthu.

Pachchamuthu joined the tea workforce at the age of 14 for a meagre wage of 75 paise per day in 1970. When he retired in 2014, he was earning Rs 250 per day. Workers now earn anywhere between Rs 332 and Rs 375 per day.

Even though many of the workers maintained close ties with their ancestral villages in Tamil Nadu, those links too seem to be fading over the years. “I have no links with my native village in Tirunelveli. However, my father used to visit the village once every year,” he says. Pachchamuthu fears if someday they are forced to leave the residential quarters, there won’t be any place which he can call home.

According to the locals, most of the lands in Munnar were leased out to Kanan Devan Hills Plantations Company (KDHP), an associate of Tata Global Beverages and the largest tea plantations company in south India.

Most Tamils, whose forefathers settled in the area during the pre-Independence era, predominantly to work in the tea estates, do not own a single piece of land in the region.

The struggle for land for these migrant workers came to light in the late 2000s when Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi (VCK), a Tamil nationalist party in Tamil Nadu, made inroads into Kerala. According to a senior trade union member in Mattupatty, it was VCK which first demanded land for the landless Tamil people in Munnar.

“Although there was huge opposition from the Malayali people, Marxist veteran and former chief minister VS Achuthanandan assured to provide land to these people in 2009,” says the trade union member.

However, even after the ruling CPI(M)-led LDF government came back to power in 2016, there hasn’t been much progress.

In the past 10 years, over 1,000 people have been forced to move out of the town after retirement. “We could not trace the whereabouts of many people. The condition of a few who are still in touch is not so good. Some of them are forced to beg in temples in cities across Tamil Nadu,” says S Vanaja, another tea worker.

Vanaja and many others in the labour lines believe the state government isn’t interested in showing urgency to provide land to the landless.

According to the revenue department officials, of the 15,000 Tamils working in Munnar tea estates, only 700 have so far got land in Munnar’s Kattayarveli. Even though 2,300 more people have got their title deeds, land plots are yet to be allocated to them.

M Priya’s parents are among those who managed to get a title deed but are still waiting for the government to allocate them a piece of land.

A BSc graduate, Priya, currently employed in a shop near Eco point in Munnar, fears that her parents would send her to work in the tea gardens, if the government fails to identify land for them soon.

“We would be able to apply for financial assistance promised by the state government only after it identifies land for us. With just a couple of months to retire, my father has asked me to make up my mind to work in the estate if things do not go well,” says a visibly worried Priya.

To add to all this, there are rumours swirling amid the mist in Munnar about preference given to tea workers from dominant caste. The air is rife with tales of discriminatory behaviour against Daits when it comes to land allottment.

R Susi, whose family roots trace back to North Madras, says that all the 700 people who were given land and subsequent funds to construct houses belong to the dominant castes.

“Though we all came from Tamil Nadu, since some of them belong to the dominant caste, they were given first preference. We were ignored by the trade unions as well as the state government because of our caste — Parayar (a Scheduled Caste),” Susi alleges.

However, MY Ouseph, Munnar town secretary of the All India Trade Union Congress for tea estate workers (affiliated to CPI), denied the allegations. “We are closely working with the tea plantation workers and have organised several protests demanding land for the landless Tamils. We will ensure that the land plots are provided to all of them without any bias,” Ouseph says.

VO Shaji, CITU town secretary (CITU is affiliated to CPM), too dismisses the allegations. He explains, “Even though initially it was described as a scheme to provide land for the landless Tamils, it has now been merged with the Kerala government’s LIFE (Livelihood Inclusion and Financial Empowerment) scheme.”

“After the LDF came back to power in 2016, the state government is working on it. It takes time to identify land. It is not just for Tamils. The stand of the party is to provide housing for all landless people in Kerala,” Shaji claims.

According to SU Rajeev, private secretary to minister for labour and excise, the authorities are closely working with the tea estate workers to provide them land deeds. “It is being delayed since there are a lot of problems in Idukki district, particularly in Munnar, over the usage of the land. The revenue department is in the process of identifying and clearing some of the revenue lands that would be given to the landless Tamils,” he adds.

But such assurances are not enough to allay the fears of Chinnathai and others in the labour lines. “We are running out of patience. Where is the time? I’ll retire in two months, where will I go then?” asks Chinnathai.