- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Sports

- Features

- Health

- Budget 2024-25

- Business

- Series

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - India-Canada ties

Govt apathy is the epidemic that's killing Bihar children

Exactly two years ago, Muzaffarpur made national headlines after finding a place in the exalted Smart City list. The much-touted Smart City Mission was launched by Prime Minister Modi in 2015 with the promise of changing urban lives and living experience in 100 Indian cities within five years. Of course, the original deadline was later extended to 2023. But even as the mission chugs towards a...

Exactly two years ago, Muzaffarpur made national headlines after finding a place in the exalted Smart City list. The much-touted Smart City Mission was launched by Prime Minister Modi in 2015 with the promise of changing urban lives and living experience in 100 Indian cities within five years. Of course, the original deadline was later extended to 2023. But even as the mission chugs towards a new deadline, Muzaffarpur continues to be living hell as it has been for decades.

As of Thursday (June 20), more than 100 children, most from economically weaker families, have died in Muzaffarpur. Hemanti Devi’s son was one of them. The young boy was out on the fields playing with his friends before he fell violently ill. The frightened family, residents of Mirhar village in Muzaffarpur district, rushed him to Sri Krishna Medical College and Hospital (SKMCH) when he started vomiting and convulsing.

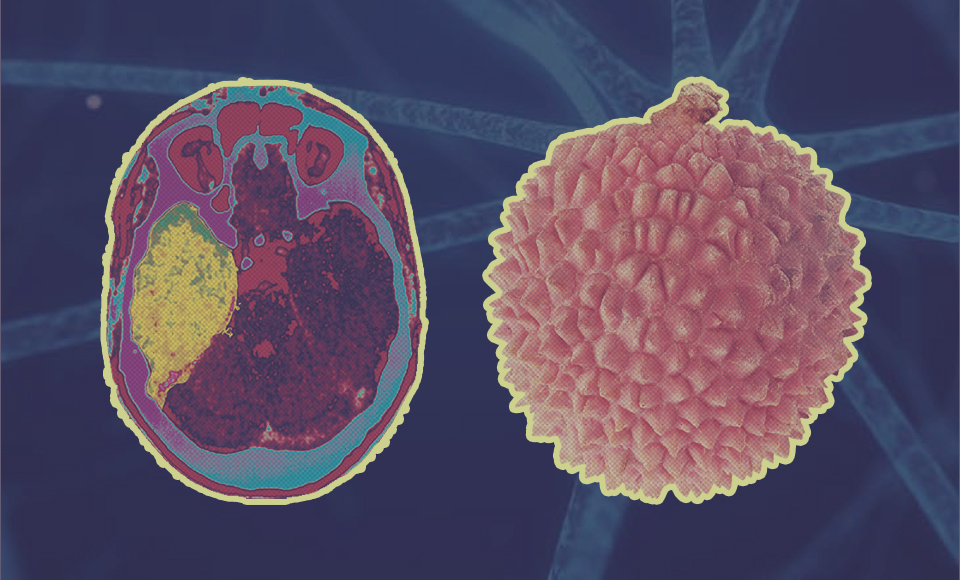

However, even as the death toll continues to rise, the actual cause of death remains a mystery with the state health department yet to identify the exact cause. While doctors maintain that the deaths are due to Acute Encephalitis Syndrome (AES), state officials claim that the victims were affected by hypoglycemia, a condition caused by low blood sugar, electrolyte imbalance due to high temperatures and extreme humidity.

What is AES and Bihar’s tryst with it

Historically, AES breakouts in India were reported in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Statistics from Bihar’s health department show that the disease claimed the lives of 143 children in 2013 and 355 in 2014. However, the death toll came down to 11 in 2015, four in 2016, 11 in 2017, and seven in 2018. In neighbouring Uttar Pradesh, encephalitis claimed the lives of 187 children in 2018 and 553 in 2017.

‘Chamki‘ fever, as the locals call it, hits Bihar’s Tirhut division, which includes Muzaffarpur, Vaishali, Shivhar, Poorvi and Western Champaran, every year during summer. Since it was first identified in 1995, research has been conducted on the syndrome but the actual cause behind the disease is yet to be found.

But this summer the death toll in Bihar shot up violently. According to a noted virologist at CMC Vellore, Dr T Jacob John, the cause of the sharp increase in death toll is the coming together of several things. The three primary factors, he says, are malnutrition among children, intense heat wave conditions, and children going to bed on an empty stomach after eating litchis. The combination of these is seen in Muzaffarpur, which is one of the reasons for the high death count.

However, there are some differences within the medical fraternity as well. Even as paediatricians in Bihar are treating the current crisis as cases of encephalitis, some of their counterparts in other states claim this could be a case of encephalopathy and not encephalitis. And the “incorrect diagnosis”, they say, may have also increased the casualties.

Encephalitis Vs encephalopathy

Dr John believes that the mystery disease is not AES, but encephalopathy. Both the diseases cause the brain to swell and show similar symptoms, such as high fever and its associated neurological conditions like mental disorientation and slipping into a coma. He says that in encephalitis, which is caused by a virus, the swelling is a result of an infection in the brain and the inflammation is limited. In encephalopathy, caused due to biochemical reactions, there is no infection in the brain but the swelling is comparatively more.

Since the brain swells more in the case of encephalopathy, patients need to be treated within an hour. In comparison, a patient with encephalitis often stays stable for at least four hours after being infected, John says. This suggests that the high death toll may be due to the delay of more than four hours of taking children from rural areas to the city hospitals.

Litchi, malnutrition or apathy is the real killer?

As the crisis spiralled out of control, a grappling administration was seen taking shield behind the seasonal fruit — litchi.

While Muzaffarpur is one of the top producers of litchi in India, Bihar produced around 3 lakh MT of litchis from its cultivation spread across 32,000 hectare in 2017, according to the Union Agriculture Ministry. Almost one-third of the litchi cultivation land is located in Muzaffarpur district.

Dr John recalls that when he was in Muzaffarpur for an assessment recently, everyone told him that no child from a well-to-do family was ill from eating litchi. In many of the villages where litchis are grown, the families are poor and children malnourished. Thus, most cases of encephalopathy, as Dr John considers it, are seen only in children from the lower income section.

“Litchi was the last straw that broke the camel’s back,” adds Dr John. The fruit does not affect children if they are well-nourished and eat meals before going to bed, he adds. Earlier, a 2017 article published in The Lancet, a medical journal, stated that lack of food (missing dinner), combined with toxins hypoglycin A and methylenecyclopropylglycine (MCPG), which are present in litchi seeds, cause the illness.

Despite all the unwanted attention the innocuous litchi has received, there are many who refuse to buy the litchi theory behind the deaths. Dr Gopal Shakar Sahni, head of the paediatric department, SKMCH, says, “I have conducted research on this disease, it has nothing to do with litchis. The disease occurs primarily due to high temperature and humidity.”

Dr Vishal Nath, director, National Research Centre on Litchi, Muzaffarpur, adds, “Litchi is being blamed for no fault of its. Litchis have grown in Muzaffarpur for the past 200-300 years but this disease is recent. Apart from Muzaffarpur, litchis are grown in districts like Vaishali, Samastipur, Begusarai, Bhagalpur, Sitamarhi and East Champaran districts as well, but there have been deaths mostly from Muzaffarpur. Why is that?”

Whether it is a reason or not, the litchi has been vilified and put through a media trial. The association of the fruit with the disease has resulted in fear among many litchi lovers, affecting the sale of the fruit. According to Bholanath Jha, a litchi grower, says, “Litchis being blamed for this disease is part of a conspiracy by the mango lobby. While mangoes are selling at barely ₹30-40/kg, litchis are sold at ₹200-250/kg depending on their quality. There have been repeated attempts to discourage litchi farming.”

With litchi being labelled the main culprit, what seems to have been brushed under the carpet is the actual state of the healthcare system in Bihar.

An ailing system

In 2017-18, Bihar allocated ₹7,001 crore on health and family welfare, which was 4.4 per cent of its total state budget allocation. But was that enough? Not really, if state Urban Development and Housing department minister Suresh Sharma is to be believed. By his own admission, lack of beds and Intensive Care Units (ICUs) was one of the factors that made the situation worse. But some attendants of patients have blamed the deaths on severe shortage of doctors.

“My daughter is in the ICU room of SKMCH. The death toll is increasing every day. There were no doctors after 12 in the night and only nurses are here. There are four bodies inside ICU,” Mohammad Aftab was quoted by ANI.

Another attendant, Sunil Ram, said, “My four-year-old daughter was admitted to the hospital on Saturday. She was declared dead today. There are no proper facilities at SKMCH.”

What makes it easy to believe devastated parents like Ram and Aftab is state Health Minister Mangal Pandey statement made in the Assembly in March last year. There is one doctor for every 17,685 people, against the national doctor-population ratio of 1:11,097, he had said.

As the death toll increased, Union health minister Harsh Vardhan promised to set up a 100-bed paediatric ICU at the SKMCH. Interestingly, he had made the same promise in 2014 as well.

Compounding the problem

The current crisis aside, doctors say there is an urgent need for increased research on AES due to the complexity of the syndrome. However, medical research in general faces a lack of attention and funding in the country.

In 2017-18, the Department of Health Research had projected a demand of ₹2,933 crore but it received a budgeted allocation of ₹1,500 crore. This impacted the implementation of schemes, including restricting the sanctioning of new units/labs on priority, providing recurring grants to ongoing projects, and upgradation of the health research infrastructure of Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR).

“There is a mismatch in the demands and funds that are granted for research,” Dr Shanthi AR, secretary of Doctor’s Association for Social Equality in Chennai, told The Federal.

(With inputs from Manoj Kumar.)