- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

The joy ride is over for Ola-Uber drivers

In 2014, 38-year-old Devaraj KJ from Mandya, a town about 100 km from Bengaluru, joined Ola. When he quit his job at a small travel company to join the giant ride aggregator, he thought a bright future lay ahead. Buoyed by the earnings of his peers, who had earlier moved to the fleet, Devaraj decided to take a chance on the tech start-up. It wasn’t long before he began earning as much...

In 2014, 38-year-old Devaraj KJ from Mandya, a town about 100 km from Bengaluru, joined Ola. When he quit his job at a small travel company to join the giant ride aggregator, he thought a bright future lay ahead.

Buoyed by the earnings of his peers, who had earlier moved to the fleet, Devaraj decided to take a chance on the tech start-up. It wasn’t long before he began earning as much as ₹70,000-80,000 a month in a car he owned attached to Ola.

However, the good days didn’t last long. “By driving in the peak hours — 5 am to 10 am and 5 pm to 10 pm — I made good money. But it didn’t last for more than two years. My income dwindled by almost 50 per cent and the work was stressful as I was driving about 15 hours a day,” Devaraj says.

Drastic change for drivers

The rise of the start-up ecosystem in India post 2010, which attracted online cab aggregating companies like Ola and Uber, also brought driver partners from villages and smaller towns to tier 1 cities like Chennai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Delhi. Lucrative incomes, hefty incentives and affordable loan schemes made drivers want to leave their hometowns and join these companies.

Their technology, coupled with cashbacks and discounts, enabled millions of people to access taxis easily in the otherwise unorganised market. And everything came handy — managed through a mobile application.

The close competition between the two major players — Ola and Uber — and their rising popularity among users helped the drivers’ salaries skyrocket. Some drivers reportedly took home ₹60,000-80,000 a month after working 15-18 hours a day. The driver partners revered Ola-Uber at one point.

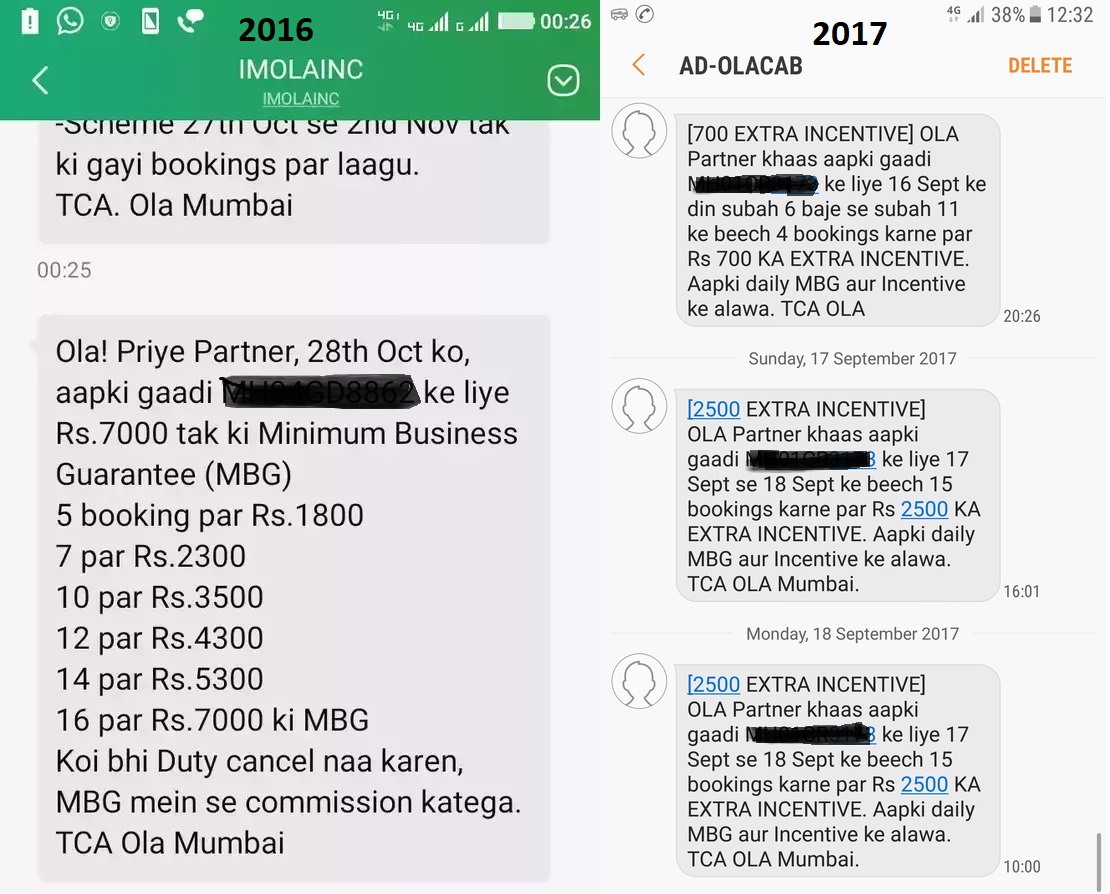

Come 2019, things have changed for the worse. The tech companies, sitting on a pile of consumer and driver data, slashed driver incentives, pumped in more cars on the road to meet the growing demand and cut down peak time charges due to regulatory challenges. They also introduced other means of rental transport in the shared-economy like bike rentals, carpooling and online autos bookings.

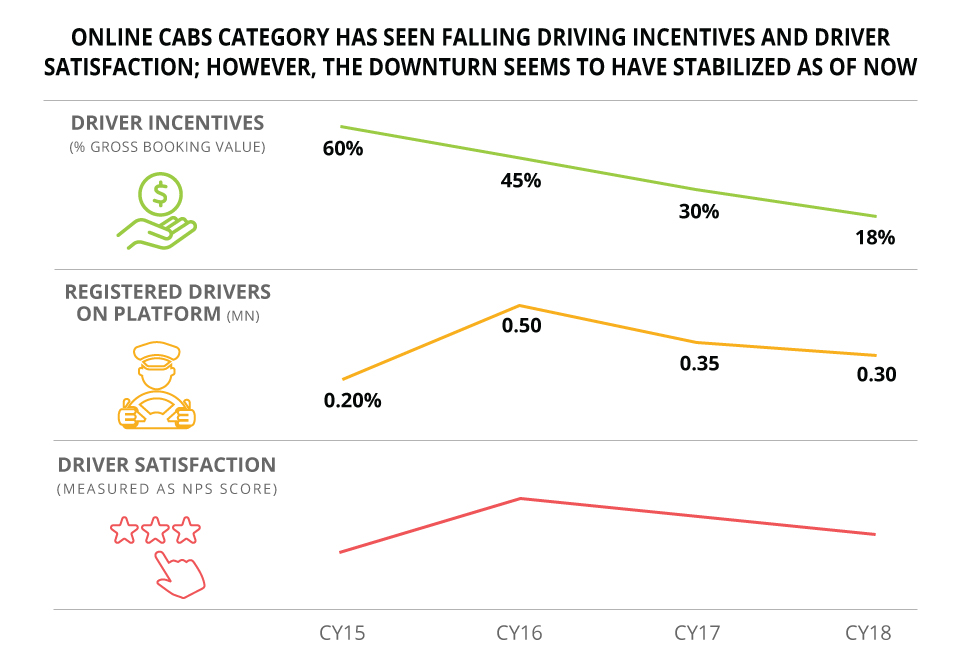

All this came at the cost of driver dissatisfaction with their incentives and earning falling consistently over the past two years.

Many drivers who this reporter spoke to across cities reportedly take home ₹18,000-22,000, an almost 70 per cent drop compared to the high in 2014-15. This corroborates with the findings of an independent consulting firm’s research report. The incentive for 15 rides a day, which was once ₹5,300 a day, is now ₹2,500. To earn that, the driver has to put in 16-18 hours on the road.

The incentives fell from 60 per cent of the gross booking value in 2015 to a mere 18 per cent in 2018. The drivers took home about 35 per cent of the booking value, while the rest went in fixed and variable costs, according to a report by Redseer Consulting, a management consulting firm based out of Bengaluru.

While some drivers left the platforms and returned to their hometowns or joined offline travel companies, many joined food-tech start-ups like Zomato, Swiggy and FoodPanda, which offered up to ₹50,000 to delivery agents.

Debt trap

There are many who fell into a debt trap as well. To meet the rise in consumer demand, both Ola and Uber entered into partnership with vehicle manufacturers and auto-financing platforms to offer lease programmes and financing options to drivers as early as 2015. But the fallout happened after two years.

With slowing down of cab booking growth and dwindling income, drivers found it difficult to manage. Take the case of 29-year-old Mahalinge Gowda who leased a vehicle with ₹30,000 down payment. The company asked him to repay ₹950 a day irrespective of how much he earned.

“Because I had to repay daily, I spent close to 16 hours on the wheel. The rides reduced over the years, incentives decreased and vehicle maintenance and diesel costs went up. I barely took home ₹12,000 monthly,” Gowda says.

“After paying about 1/3rd of the money, I returned the vehicle as I could not repay them. Now I drive my own vehicle and take home ₹20,000 and manage my own finances,” he adds.

The economics of it all

One of the reasons so many drivers fell into this trap is because they didn’t understand the economics of it all. It’s only when they start working do they realise how unfeasible the business model is.

Devaraj, who joined the platform two years earlier, quit in late 2016 to join a company that offered a regular monthly salary. But in less than a year he quit to try his luck with Ola again. But it’s not worth it, he says.

“When I rejoined, I took home less than ₹20,000 a month. It wasn’t worth the effort. In 2018, I quit for good to join a travel company that offered me ₹35,000 a month for working between 10 am to 8.30 pm,” Devaraj explains.

Devaraj says he never understood the economics as there were no hard copy receipts but only digital (app-managed) summary sheets that went over his head.

Some drivers unwittingly fell for the lease programmes and financing options. Gowda, with his hatchback, earned a gross income (including incentives) of ₹80,000 per month, out of which he spent ₹28,500 on repaying the loan, ₹22,000 on fuel, ₹4,000 on commercial tax, ₹700 on insurance, ₹4,500 for vehicle maintenance, and ₹1,000 on phone and internet charges. After that, he took home ₹19,300 on an average. This was pretty much what the offline transport companies offered.

Another cab driver sums it up well: ‘We were shown biryani but ended up eating curd rice.’

Uber drivers narrated similar stories as well. They alleged that cab aggregators charged about 30 per cent commission on the gross booking value. When it came to ride-sharing services, while many drivers felt it was environment-friendly, it wasn’t economically viable for them. Karnataka recently banned ride-sharing services as it violated the existing transportation laws in the state.

History of conflict

The online cabs category historically witnessed a high number of conflicts between driver partners and the cab aggregators. Protests have erupted on many occasions in Mumbai Kolkata, Chennai, Bengaluru and Hyderabad, with drivers asking the companies to adhere to the promises made on commissions and assuring minimum number of rides every day.

On July 1 and 2, about 25,000 cabs in Kolkata went off the road in protest against exploitation of drivers.

Before the Karnataka Assembly elections in 2018, Chief Minister HD Kumaraswamy planned to start HDK Cabs in a bid to take on Ola and Uber, with the support of a few drivers. However, it did not materialise.

Tanveer Pasha, president of Ola, Taxi-For-Sure, Uber Driver’s and Owner’s Association, which has close to 18,000 members in Bengaluru, says many of the complaints that they receive are related to debt and blacklisting of drivers for unnecessary reasons. Both, Ola and Uber blacklisted Pasha and a fleet owner after he organised a protest in 2017.

“The cab sector was at the forefront of creating more self-employment. But if driver partners continue to fall into the debt trap and make losses, the industry will lose its sheen,” Pasha says. “While the companies need to step up, the government needs to step in and regulate this industry to protect the interest of drivers,” he adds.

As the industry matures, Ola and Uber are focussing on profitability and cutting costs. With high demand in metros and tier 1 cities, the number of taxi rides now account for 65 million rides a month on an average while the auto rickshaw segment clocked 18 million rides a month, as per Redseer report.

Commenting on the industry development, Ujjwal Chaudhry, associate director, RedSeer Consulting, says that the cab aggregators realised that discounted rides cannot keep them running and they are now cutting on losses by trimming the expenses.

“The online cab market is maturing and the industry is stabilising. These (Ola-Uber) are businesses that need to sustain and make profit someday. They cannot sit on mounting losses. So, it was natural for them to increase commission and cut down losses,” Chaudhry opines.

While Ola declined to comment on the story, Uber did not respond to the e-mail sent by The Federal.