- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Scars of civil war haunt Sri Lankan Tamils 12 years on

In January this year, the Sri Lankan government razed to the ground the war memorial at Jaffna University which stood to commemorate thousands of Lankan Tamils who died in the protracted civil war in the country. The bulldozers that were brought in to erase the signs of the war, however, have failed to wipe out the memories of the deaths and funerals that the dead were denied from the minds...

In January this year, the Sri Lankan government razed to the ground the war memorial at Jaffna University which stood to commemorate thousands of Lankan Tamils who died in the protracted civil war in the country. The bulldozers that were brought in to erase the signs of the war, however, have failed to wipe out the memories of the deaths and funerals that the dead were denied from the minds of Sri Lankan Tamils.

The government’s missing attempt at reconciliation with the Tamil population has exacerbated the hurt and alienation of countless Tamils left in Sri Lanka and even those living outside. Twelve years after the war, there is no sign of the promised government commissions to probe the 1,000s missing persons or a war crimes tribunal to investigate human rights abuses.

Political observers say the future of Sri Lankan Tamils looks grim and “uncertain” amid rallies to protest land grab in Tamil areas, government-sponsored Sinhalese settlement, enforced disappearances and persisting militarisation among others. Patience is running out for people in the absence of an able leadership, as experts point out, the Sri Lankan Tamil leaders are opportunists who have made peace with the ruling government for their own gain.

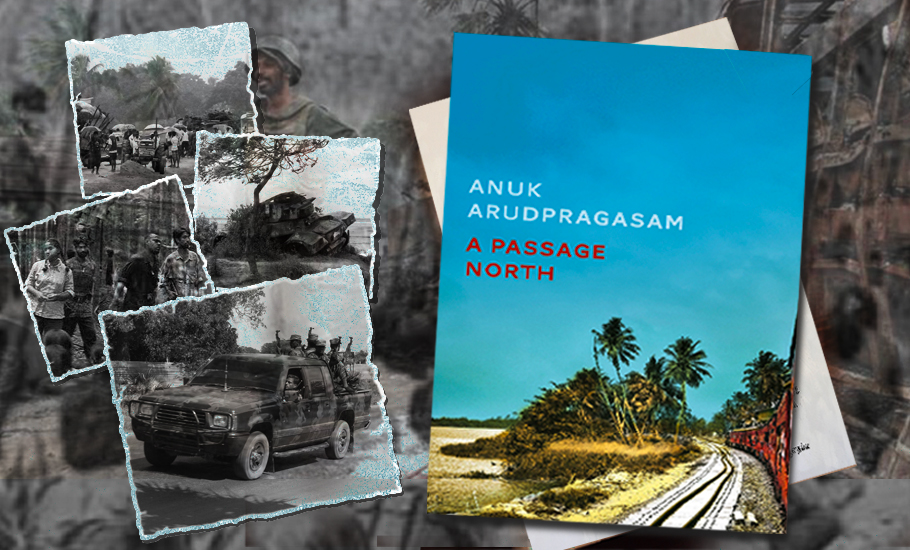

Some like Anuk Arudpragasam have found a vent in fiction to express the despair and draw attention to the sense of injustice countless people are living with.

Arudpragasam’s Booker Prize-shortlisted novel A Passage North is a profound, meditative account of the legacy of the long-drawn, bloody civil war in Sri Lanka. The book is a song of lament, an unrelenting outpouring of ‘guilt and shame’ raking up the wounds of a three-decade old conflict that had violent repercussions in the region. Arudpragasam’s book echoes the sentiment of countless others like him.

Writing the novel was a ‘form of punishment’, admits 32-year-old Sri Lankan Anuk Arudpragasam at a public discourse on his book. He wrote it to punish himself for being a mute witness to the ‘indescribable violence’ unleashed under the averted eyes of the international community in northern Sri Lanka by the country’s armed forces in the final days of the conflict in 2009.

According an imaginary funeral

The Sri Lankan armed forces finally won the war against the militant Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) after the killing of their supremo Velupillai Prabhakaran. While the United Nations accused both sides of atrocities, international rights groups have claimed that at least 40,000 ethnic Tamil civilians were killed in the final stages of the war. The Sri Lankan government has however disputed these figures.

Arudpragasam, who hails from a Tamil family of means in Colombo, and grew up far away from the war in north-east Sri Lanka, where his family is originally from, did not set out to write about the war. But after witnessing the “government’s systematic destruction” of Tamil society during the final phase of fighting, the images and memories continued to haunt him. (His first novel the Story of a Brief Marriage too is set against the backdrop of this civil war.)

“I don’t think it is just me, many young Tamils my generation are unable to stop thinking about this war,” says Arudpragasam in an online interaction with Bengaluru-based Champaca Bookstore. In the book, the protagonist Krishnan, a Tamil untouched by the civil war, journeys from Colombo to north Sri Lanka, to attend the funeral of his grandmother’s caretaker, Rani. On the train to battle-scarred north, he ruminates about time, trauma, longing, love and weaves in stories about the doomed Sri Lankan Tamils fight for a separate homeland that went horribly wrong. He reaches Kilinochchi, the former capital of the disbanded LTTE, and attends Rani’s funeral which he describes in detail over 100 pages.

But Arudpragasam had his reasons. According to him, in 2009, as Sri Lankan Tamil residents fled the shelling of advancing military forces, families had to leave behind the bodies of their loved ones killed in the bombing. “They had no choice, when caretaker Rani’s son in the book is hit by shrapnel pieces and dies, she had to leave him there and run from the shelling to protect her daughter and herself. So, I devoted 100 pages to Rani’s funeral as an act of catharsis,” says Arudpragasam. Quite simply, he wanted to give all those dead in the Sri Lankan civil war an imaginary funeral, exhaustively delineating each step of the rites.

Arudpragasam, who has a PhD in philosophy from Columbia University, ultimately describes his book as a ‘study on longing’. The longing for a renewed ‘new future’ built on the ruins of a broken tattered society.

Arudpragasam, who concludes nothing has changed for the community, says, “When the war just ended, I hoped like Krishnan in the novel that a new future will flourish from the ruins of this society. Something new can be built, but as time passed and nothing changed, it has become clearer to me that some people will remain scarred forever and can never move on.”

Erasing signs of war

Much like the war memorial in Jaffna University, the Sri Lankan government has erased all signs of the civil war. Arudpragasam draws a parallel in book when he recounts how the “Chinese-made bulldozers had mowed down cemeteries of dead fighters who had died fighting for a future that never materialised”. But, like Krishnan does in A Passage North, the several signposts of the civil war can still be elaborately constructed in the minds of the Tamil people, much like the imaginary temple Poosal, the poor, ardent devotee of Lord Siva had meticulously builds in his mind in a legendary Tamil poem that Arudpragasam so masterfully and evocatively draws from to convey his own obsessive construction of the war.

The despair Tamils experience hangs like an ominous cloud over the country. The Tamils on the island are a bitter and crushed community today. “The trauma of war is not a trauma which can be undone in a day, or a decade,” points out Chennai-based poet, novelist and activist Meena Kandasamy, author of The Orders were to Rape You, which documented the hard-hitting first-person experiences of two women of the Tamil Eelam, who are also battling with the inherent biases of a patriarchal Tamil society.

“Eelam Tamils have faced structural oppression since the 1950s, and extremely violent oppression since the 1980s. The culmination of all of that was the genocidal killings in 2009,” Meena points out, adding that books by Arudpragasam and others like Sugi Ganeshanantha’s Love Marriage, Theepachelvan’s Nadukal and the memoir of late S Thamilini, the head of the LTTE political wing effectively capture the struggle.

Kandasamy adds that the Tamils are still living under a “genocidal Sinhala majoritarian regime” resisting a state ban on memorialisation. But their resistance is peaceful, with mothers demanding accountability and answers for disappeared children, she says, giving the example of the recent peaceful ‘Pothuvil to Polikany’ rally to protest against land grab in Tamil areas, Sinhalese settlements in Tamil areas and enforced disappearances among others.

“The scars of war have not prevented them from standing up for their rights. In fact, it appears that protest is the only way in which they can survive and safeguard the dwindling rights they have,” she says.

A long winter of discontent

Victims of the 30-year-long conflict are still finding it hard to deal with the trauma. “The Sri Lankan Tamils, who form about 11.5 per cent of the island population, have been through untold misery and hardship. An old man in a refugee camp in Chennai who had watched his wife and daughter being raped is yet to recover from the trauma. There are 800,000 Tamils left, so many have died, but government data doesn’t show the decline in their population,” says V Suryanarayan, former founder of Centre for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Madras.

According to Suryanarayan, who is an expert on Sri Lankan affairs, Sri Lankan Tamil leaders have failed the Tamils. “They are collaborating with leaders whose hands are tainted with blood,” he says with grim emphasis. Moreover, no amount of Tamil insistence will ever lead to the merger of the north and eastern provinces of Sri Lanka, a long-standing demand of the Eelam Tamils, he adds.

The Tamils are majorly represented by Tamil National Alliance (TNA) led by veteran politician R Sampanthan. But with the government dragging its feet about holding provincial council elections, the Tamils have no forum to voice their concerns, he says. “The Indian government keeps parroting about honouring the 13th amendment but the majoritarian Sri Lanka government turns a deaf ear, claiming it is an internal matter,” points out Suryanarayan.

(The 13th Amendment was the outcome of the India-Sri Lanka Accord of July 29, 1987, signed by then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Sri Lankan President JR Jayawardene. Passed by Sri Lankan parliament in November 1987, it resulted in creation of provincial councils but the devolution of power to the local governments as envisaged by the amendment has remained a pipe dream.)

According to Dr Kandiah Sarveswaran, former lecturer at University of Colombo and former minister of education sports culture and youth affairs, Northern Provincial council, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, is not interested in holding elections and would only too gladly scrap the 13th Amendment or dilute its provisions.

In an interview to The Federal from Sri Lanka, Sarveswaran, who says the government has not held the elections for the past three years, however, holds the view that the current provincial system is extremely ‘weak and vague in terms of power sharing’.

“There hasn’t been a proper devolution of power. The Tamils are totally under the thumb of the government, the Buddhist Sinhala polity view us as if we are insects. If you want rights, go to India is what they say,” says Sarveswaran wryly. He is also the assistant secretary of Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) and like most Tamil nationalist political parties. Sarveswaran wants minimum substantial autonomy in the north and eastern provinces.

“The Rajapaksa government is unquestionable and uncheckable, while the Sinhalese are pushing the sons of the soil theory,” he adds. The mood is one of disappointment and questions of our survival stare us in the face, says Sarveswaran.

“It finally boils down to the question of protecting our identity and our very existence. Sri Lankan Tamil speaking people – the Tamils who came to work on British plantations, the north eastern Sri Lankan native Tamils and Islamic Tamils make up 25 per cent of the population in Sri Lanka. But our population is slowly dwindling, 300,000 Tamils have died in this protracted war from 1983 to 2005. The rate of growth of Tamils (sans Muslim Tamils) has stayed at 1.5 per cent for the past five to six years,” he says.

A lost dream

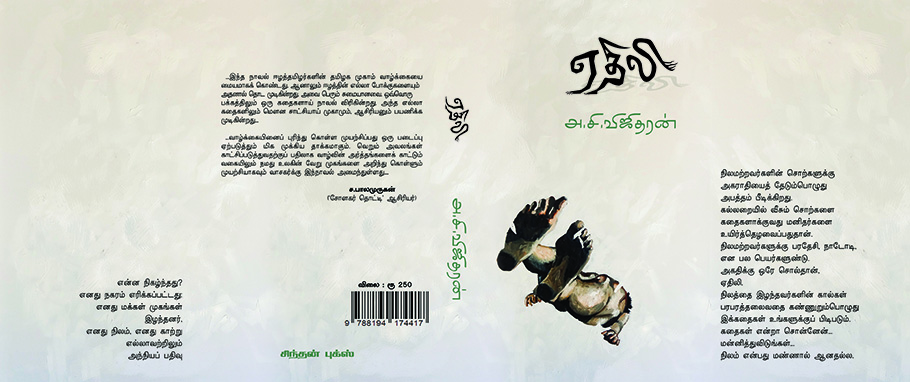

Vijitharan, a Sri Lankan Tamil writer, who fled to India in 1996, is attached to a refugee camp in Erode. An ‘anguished’ spectator of the war, he blames the LTTE, the Tamil parties and the Tamil diaspora for the situation the Tamils find themselves in today.

“In 2006, the Tamils were not ready to face the war but the LTTE, which alienated everyone around them, including Tamil Muslims, dragged them into it. They were annihilated and left the hapless Tamils rudderless. There are 80,000 people still living in camps without basic amenities – be it water, food, housing and education. Families of missing persons are continuously protesting but they don’t seem to have any voice or visibility. Having lost all hope, they have even voted for Rajapaksa in the recent presidential elections,” says Vijitharan, who has been hired as a script-writer for a Tamil film after he wrote the novel Yeethili (refugee).

The idea of Tamil nationalism in Sri Lanka has failed, he says. Suryanarayan too echoes this point as he says the dream of a Tamil Eelam exists only in the minds of the diaspora but not in Sri Lanka. But if the government fails to provide a “constitutional solution” that can lead to ethnic reconciliation, the resistance will resurface one way or the other. It can either be the Gandhian way or through another violent movement, he reckons.

“The TNA may say there is no possibility of the LTTE coming back but one cannot hazard a guess about what the future holds,” says Suryanarayan.