- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

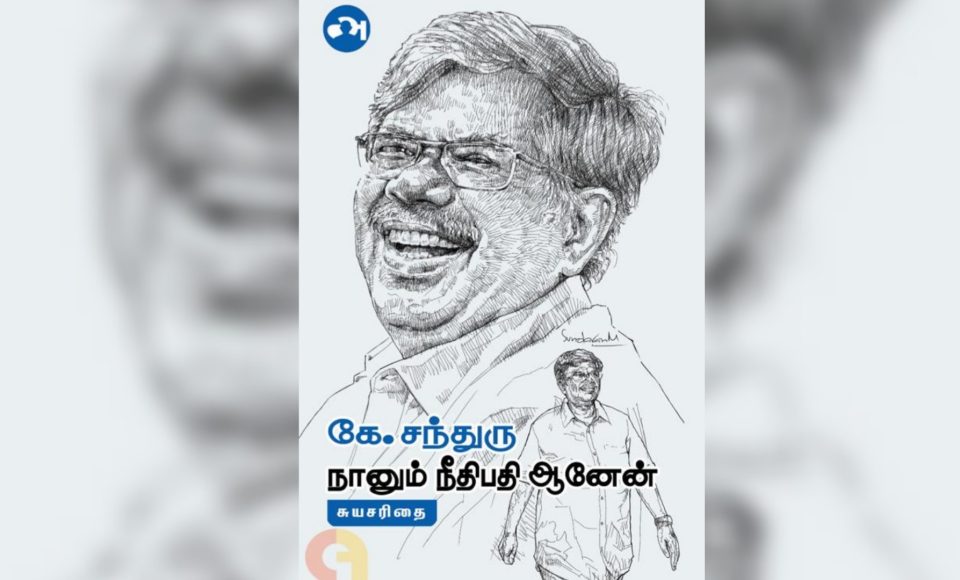

Real-life Jai Bhim hero K Chandru pens a tell-all memoir

It was just another sultry day in Chennai of the 1940s. Krishnaswamy, a railway clerk, was hanging out at the iconic lighthouse on the Madras High Court premises with his wife Saraswathi, a daughter and two sons, who had moved from Trichy to Chennai just a couple of months ago. Having explored the lighthouse, Krishnaswamy’s family was walking through the corridors of the court when...

It was just another sultry day in Chennai of the 1940s. Krishnaswamy, a railway clerk, was hanging out at the iconic lighthouse on the Madras High Court premises with his wife Saraswathi, a daughter and two sons, who had moved from Trichy to Chennai just a couple of months ago.

Having explored the lighthouse, Krishnaswamy’s family was walking through the corridors of the court when their peaceful stroll was interrupted by a macebearer trying to tell the people around to make way for the judge. Instead of a polite vazhi vazhi (excuse me), the macebearer created rude sounds of ‘ush ush’ to tell people to clear the way.

Somewhat awed by the power the judge wielded, Saraswathi asked Krishnaswamy if her sons could ever command power like the judge.

“Why not,” said Krishnaswamy.

Many years later, K Chandru, who was not born when the incident happened, indeed became a judge and lived a life so accomplished that a movie, Jai Bhim starring Suriya, was made on one of his many achievements. Only he never allowed macebearers to clear the way for him.

“I lost my mother when I was five years old. The story was told to me many years later. If my mother would have been alive, she would have been happy to see her son as a judge. But she wouldn’t have seen the macebearer because I have done away with the colonial practice,” writes justice (retired) K Chandru, in his recently released memoir Naanum Needhipathi Aanen (I Too Became A Judge).

The book, a tale of many unsettling truths, unravels the story of how politics and judiciary crossed roads in Tamil Nadu while K Chandru served at the Madras High Court. The encounters were mostly unpleasant.

But what happened before K Chandru became the judge his mother had wanted one of his sons to be?

K Chandru, who now dons many hats, including being an erudite lawyer, involved activist, and prolific writer, did not have an easy journey. His elevation as a judge was expected way back in 2001 but due to the politics surrounding appointment of judges—which he has extensively written about in this book—he lost the chance. He lost another chance to become a judge in 2004. He was only appointed a judge in 2006.

Noted legal luminary VR Krishna Iyer, wrote a letter to Chandru after the latter’s appointment as a judge saying:

“My dear Chandru,

…You have a great future to be faced with courage, integrity, erudition and commitment to the common people including Adivasis of our country. You have miles to go and promises to keep at a time the judiciary as class is failing in its Dharma.”

On his part, K Chandru has kept his promises and crossed many unprecedented milestones—one of which was dispensing 96,000 cases during his six-and-a-half-year tenure as judge. What motivated Chandru to achieve the feat was his steadfast belief and faith in one of the pledges taken by the legal fraternity, “We acknowledge the social responsibilities and the professional obligation of law in public interest and public service.”

The former judge was able to go beyond his call of duty and richly contribute to his field by holding firm to his pledge.

The humble beginnings

Chandru was the fourth child and the third son to his parents. His parents went on to have a son after Chandru’s birth.

“After my sister, the eldest among us, got married, we, the brothers, lived with our father. We did all the household chores. Mostly, I did the cooking part. When I was 15, I lost my father. At that time, my eldest brother was in the United States and my second brother was studying at IIT-Kanpur. I carried out the last rites of my father since no elder was around,” he said.

Despite scoring good marks in the school’s final exams, Chandru was unable to fulfil his dream of becoming a doctor. So he joined Loyola College in Chennai and took an undergraduate course in Botany. It was in college that the activist in Chandru began to take shape. He organised a protest against the Loyola College administration seeking reduction in the high mess fees and got barred from the college as a result. He later joined Madras Christian College and completed his graduation from there.

After sending his younger brother to Trichy to pursue studies, Chandru, who was attracted to Communist ideology during his school days, became a loner. He found his refuge in books. A voracious reader, Chandru was also deeply influenced by Periyar’s ideology.

“In the 1970s, the student uprisings were happening world over. The ripples of student revolutions in France (May 1968 protests) and the US (against the Vietnam War) had reached India. Tamil Nadu too wasn’t left untouched. At the age of 20, I too plunged into student politics. I became a member of Communist Party of India (Marxist). My fellow cadres were my relatives and we operated from my home then [Chandru considers the party office as his home],” he said.

Around this time, Annamalai University was hit by a huge storm which also in a way gave K Chandru a direction in life. The students were miffed over lack of jobs when the university decided to award an honorary doctorate to Karunanidhi. The decision sparked off protests on the campus, which a rattled government met with brute force. Udhayakumar, a student of the university, was killed in a police crackdown on students protesting on the campus.

Chandru along with his batchmates and friends including The Hindu’s N Ram, veteran Congress leader P Chidambaram and CPM senior leader G Ramakrishnan, worked to bring out the truth of the police’s attempt to suppress the voice of the students. Under pressure, the DMK government ordered the setting up of Justice NS Ramasamy Commission to probe the incident.

Chandru deposed before the Commission too. Seeing his eye for details, Ramasamy through one of Chandru’s friends advised him to enrol in a law college.

“Later, KK Venugopal (the current Attorney General), under whom Chidambaram was practising then, too advised me to study law. So, I joined law college in 1973 and in 1976, I registered myself as an advocate and started practicing at Row and Reddy specialising in labour related cases,” he said. After seven years, he started his own practice.

Intersection of politics and judiciary

One of the beauties of K Chandru’s memoir is that the book reads like an account of the contemporary political and judicial history of Tamil Nadu. The writer also pulls no punches and provides vivid details of how politicians, including chief ministers, tried to ‘settle scores’ with him.

The politics over Udhayakumar’s death was one of the many such cases. Being a student activist, Chandru had taken help from Chidambaram to fight the case. Once when Chandru and Chidambaram were travelling together from Chennai to Cuddalore district, where the university is located, they were denied rooms in the university hostel despite having booked the rooms in advance. The political pressure was evident. While writing about the incident, Chandru says, “Chidambaram is the grandson of Annamalai Chettiar, who founded the university. Despite that he experienced this in Chidambaram (the place where the university is located).”

A few years later, when Emergency was imposed and the Tamil Nadu government was dismissed, DMK leaders faced police atrocities in jail. Pon Paramaguru, a Thevar, headed the prison department back then. According to Chandru, Paramaguru was the key player in unleashing atrocities on the prisoners who were detained under Maintenance of Internal Security Act. During an instance of custodial police brutality, Chittibabu, former mayor of Chennai and DMK leader, died.

Later, when AIADMK formed the government, it appointed Justice Ismail Commission to probe Chittibabu’s death. The Commission’s recommendations, which were never implemented, included prison reforms and departmental action against guilty police personnel.

Chandru appeared as an advocate for the Communist leaders. While writing about the matter, Chandru says that if marks were to be given for the implementation of recommendations made by the Commission, the goverment would get a zero.

It was during the time of Pon Paramaguru, who was later elevated as the DGP of Tamil Nadu, that many youngsters from Thevar caste, a backward community, joined the police force that gave them an upper hand over Dalits.

The next political attack on K Chandru came in 2003 when Nepali communist leader Chandra Prakash Gajurel, accused of being involved in guerrilla warfare, was detained for holding a forged passport while trying to flee to London from Chennai. In subsequent months, the then J Jayalalithaa government tried to extradite him, a decision that would have sealed the end to Gajurel’s life. But due to protests from the human rights organisations in the state, Gajurel was allowed to remain in Chennai. Chandru appeared as the counsel for Gajurel.

“I was called an ‘advocate for international terrorists’ by Jayalalithaa, who opposed my name for the judgeship when collegium recommended me because I represented Gajurel,” he writes.

Writing about how the Tamil Nadu State Human Rights Commission was given a new lease of life, justice (retired) Chandru refers to the case of now suspended IPS officer Rajesh Das, who sexually harassed a woman IPS officer. The book reveals a so far unknown fact. Chandru writes that Das was punished by the Tamil Nadu State Human Rights Commission in 2000 for attacking two police personnel who allegedly teased his wife Beela Rajesh, an IAS officer, while she was playing badminton at the Armed Forces Ground in Trichy.

“He was ordered to pay Rs 5 lakh as compensation to the police personnel and the Commission directed the state government to collect the compensation from the officer. However, he filed a writ petition in the Madras High Court and got a stay. After 10 years, when it was heard by justice Nagamuthu, he said that the government cannot straightaway prosecute the official concerned on the basis of the Commission’s recommendations.

Finally, in February 2021, a three-judge bench upheld the Commission’s recommendations and said the observations of the single judge is wrong,” Chandru writes.

Landmark judicial interventions

Chandru’s works in the legal field have set some benchmarks for lawyers. For instance, he never entertained boycotting courts. As a judge, he put an end to the practice of being guided by the macebearer from the office to the courtroom. He ordered advocates not to use salutations like ‘My Lord’, another colonial practice. He denied personal police security.

He abnegated organising a farewell function on his retirement. He also played an important role in establishing the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court and hence, he was seen as a ‘hero of the Madras High Court’ by the advocates of Madurai.

On the face of it, these may look like stunts enacted to earn the goodwill of the public, but it is not only these actions that earned Chandru people’s respect. His judgements dispensing justice in the light of Dr BR Ambedkar’s ideologies earned him the love of the masses.

It was justice Chandru’s 2010 ruling in the D Pothumallee and others vs District Collector, Tiruvarur, that paved the way for 25,000 Dalit women to get reservation in Anganwadi jobs.

Known for his speedy disposal of cases, Chandru devised a method to dispose of cases related to adoptions speedily. Before 2009, there were thousands of adoption cases pending before subordinate courts.

“One of the reasons why the subordinate courts were hesitant to take up adoption cases was because there was no target for disposing such cases. Each subordinate court has a monthly target to dispose of the cases now. But in those days, the targets were set only for civil and criminal cases. If the targets were not achieved, the judges of those courts would get black marks. Even though they hear adoption cases, those would not add to the target count. Hence the judges never gave preference to those cases,” Chandru said.

When hearing of adoption cases was also assigned targets, the number of pending cases came down from three-digits to single-digit in every court.

Not all the judgments he pronounced brought him bouquets. Some brought brickbats too. For instance, when justice Chandru ordered that no one should claim copyrights for Periyar’s writings, K Veeramani, the petitioner of the case and chief of Dravidar Kazhagam founded by Periyar, criticised him in his daily Viduthalai saying “it is better if the judges give their judgements within the judicial territory. Their sermons are unnecessary”.

Similarly, when he ordered that the media cannot be restrained from publishing news just because someone is in public life while hearing a petition on behalf of DMK leader A Raja then mired in the 2G scam, he got threats in the form of handbills. A report published by The Pioneer later revealed that the handbills were faxed from Raja’s office in Delhi.

None of it managed to deter the maverick in K Chandru.

Many came to know about him when Jai Bhim (2021) released on OTT. The film, however, explores just one of many contributions, K Chandru has made to society during his life.

The book provides the full picture.