- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

On Mother’s Day, stories of lifelong daughters and queer mothers

Mother’s Day is just around the corner and it is always a tough day in my house. It brings into focus all the fragmented thoughts about mothers — my cousin who lost his mother to covid, how must he feel today; my mother is worried about her ageing mother’s health; my sister and I worry about our mother’s frozen shoulder. I remember the day my mother asked me to put eyeliner on her,...

Mother’s Day is just around the corner and it is always a tough day in my house. It brings into focus all the fragmented thoughts about mothers — my cousin who lost his mother to covid, how must he feel today; my mother is worried about her ageing mother’s health; my sister and I worry about our mother’s frozen shoulder. I remember the day my mother asked me to put eyeliner on her, and for the first time, I noticed her first wrinkles as I struggled to outline her droopy eyelid with eyeliner. Where did her youth go?

My mother dislikes being outdoors and she is not a fan of the treats my sister and I cook at home. She says all this is not good for her diabetes. She says she has too many clothes and she hardly wears any jewellery. It becomes difficult for us to think of the appropriate mother’s day gift for her. We know when she opens her WhatsApp, many chat groups will be flooded with celebratory messages for Mother’s Day, and we will feel guilty for not gifting her clothes and chocolates. As I said before, Mother’s Day is complicated.

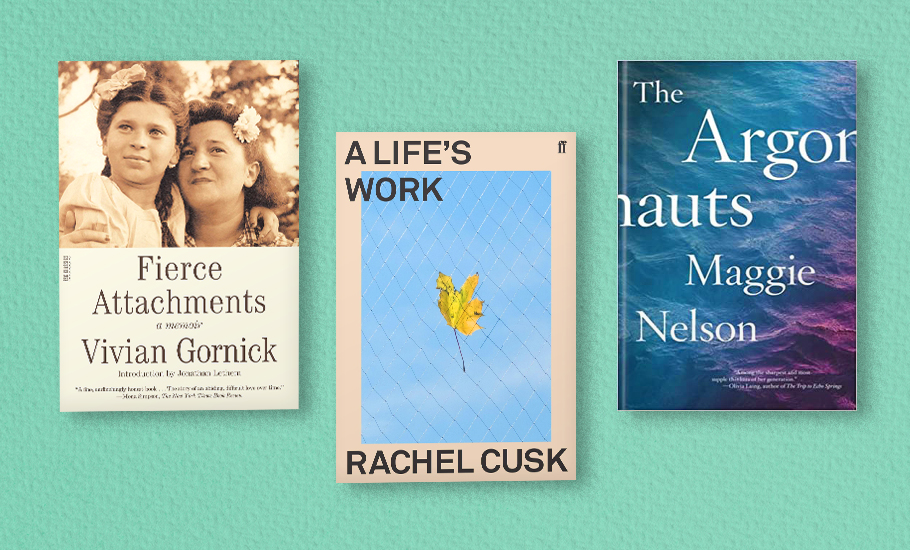

My response is to read about mothers and try to make sense of everything. I have an odd obsession with the topic of motherhood, its secrets and its mysteries. I have been obsessively picking up books about mothers and daughters from bookshelves ever since I was 20 years old. Every year I do a Mother’s Day reading project, and for this year I chose to explore the strange crevices of motherhood through three works of non-fiction written by women about mothers and motherhood- three accounts which could not have been more different from one another.

Fierce Attachments by Vivian Gornick

Vivian Gornick’s brilliant memoir explores her strongest attachments to the women in her life, the fiercest being the attachment between Gornick and her mother, a Jewish communist woman who came to widowhood early in life. There comes another woman, Nettie, in their lives who threatens to alter their bond. However, Gornick will continue her attachment to her mother late into her life, their bond as strong and as strange as ever because they will always be mother and daughter. Their relationship unfolds through walks in New York, against the backdrop of working-class life in the 20th century, the sexual rage of women, and the relationships that matter the most in life.

Fierce Attachments illuminates the relationship daughters have with their mothers — how daughters can try all their life not to act like their mothers, and yet in the process become exactly like their mothers, inheriting the peculiarities that they find ridiculous. The reader comes to see many sides of motherhood — the good, the bad and the ugly. Motherhood can encompass everything in its fold — immense love and passionate violence. Before she became a mother, Gornick’s mother stood in public spaces giving passionate speeches about communism. She sacrificed her freedoms for marriage and then she sacrificed sexual joy for the good of her children. Her terribly romanticised marriage came to an end with her husband’s death.

‘…and we become what we often are: two women of remarkably similar inhibitions bonded together by virtue of having lived within each other’s orbit nearly all their lives. In such moments the fact that we are mother and daughter strikes as an alien note. I know it is precisely because we are mother and daughter that are responses are mirror images..’

Admiring your mother’s motherhood can suffocate you when you realise that her life was limited because she nurtured your life. It was an unfair exchange. She did not get to live her life. Out of this comes attachment and expectation, which if not fulfilled can turn dangerous.

Gornick also writes about what it is like to grow up with a depressed mother.

‘Weekends, of course the depression was unremitting. A black and wordless pall hung over the apartment all of Saturday and all of Sunday. Mama neither cooked, cleaned, nor shopped. She took no part in idle: the exchange of banalities that fills a room with human presence, declares an interest in being alive.’

Gornick’s mother romanticised her marriage, and later she romanticised widowhood.

‘In refusing to recover from my father’s death she had discovered that her lie was endowed with a seriousness her years in the kitchen had denied her.’

The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson

Maggie Nelson talks about the desire for experiencing motherhood with her non-binary partner Harry Dodge in Argonauts. It is a desire that she cannot explain, a desire she had given up until recently.

‘You pass as a guy; I, as pregnant. Our waiter cheerfully tells us about his family, expresses delight in ours. On the surface, it may have seemed as though your body was becoming more and more “male”, mine, more and more “female”. But that’s not how it felt on the inside. On the inside, we were two human animals undergoing transformations beside each other, bearing each other loose witness. In other words, we were aging.”

Fragmented in text, Argonauts is a memoir of Nelson’s first pregnancy, written when Nelson is four months pregnant and Dodge 6 months on T as they both go through transitions. Nelson experiences pregnancy as a queering of the body, as a phenomenon very radical and wild in nature. On the other hand, she also describes the isolation of the experience of childbirth. In vivid detail, the reader is taken through the motions of childbirth which she compares to “touching-death”. She explores all aspects of motherhood with the same raw honesty, with an intensity that makes it hard to look away. There is love and pain in equal parts as she talks about what parenthood looks like for a queer couple. Throughout the trials and tribulations faced by the couple, Nelson has only love for her stepson and her newly born son.

A Life’s Work by Rachel Cusk

Rachel Cusk writes about being a prisoner of pregnancy and about the isolating act of caretaking. She feels all her privacy vanish as her body starts to show external signs of pregnancy. She writes about the policing of pregnant bodies. With breathtaking prose, her writing reflects the inequality of the sexes with regard to parenthood.

‘It is one solution for the father to remain at home while the mother works: in our culture the male and the female remain so divided, so embedded in conservatism, that a man could perhaps look after children without feeling that he was his partner’s servant. Few men, however, would countenance the injury to their career that such a course would invite; those who would are by implication more committed than most to equality, and risk the same loss of self-esteem that makes a career in motherhood such a difficult prospect for women.’

Cusk’s writing cuts through the mystery of childbirth and postnatal care. She approaches different stages of her pregnancy and later the growing up of her daughter with the same honesty and intensity. There is, once again, love and pain in equal parts as Cusk struggles to take care of her daughter all by herself and wonders if she is going mad from isolation. She feels lost and confused as she wonders whether or not her daughter likes her.

A Life’s Work is a witty and moving memoir of Cusk’s pregnancy, the birth of her daughter, her daughter’s colic, sleepless nights and self-doubt. It elicited a strong vitriolic reaction from many readers as Cusk wrote fearlessly about the loss of freedom and self that her daughter’s birth marked. But what Cusk offers is companionship to mothers everywhere and she breaks the silence around the grief of pregnancy and motherhood.