- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Madurai and the making of the Mahatma and his Khadi revolution

Khadi to me is the symbol of unity of Indian humanity, of its economic freedom and equality and, therefore, ultimately, in the poetic expression of Jawaharlal Nehru, ‘the livery of India’s freedom’ – Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Who doesn’t know the story of a frail man in a loincloth sitting behind the charkha, spinning a revolution. Yet many may still not know in...

Khadi to me is the symbol of unity of Indian humanity, of its economic freedom and equality and, therefore, ultimately, in the poetic expression of Jawaharlal Nehru, ‘the livery of India’s freedom’ – Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

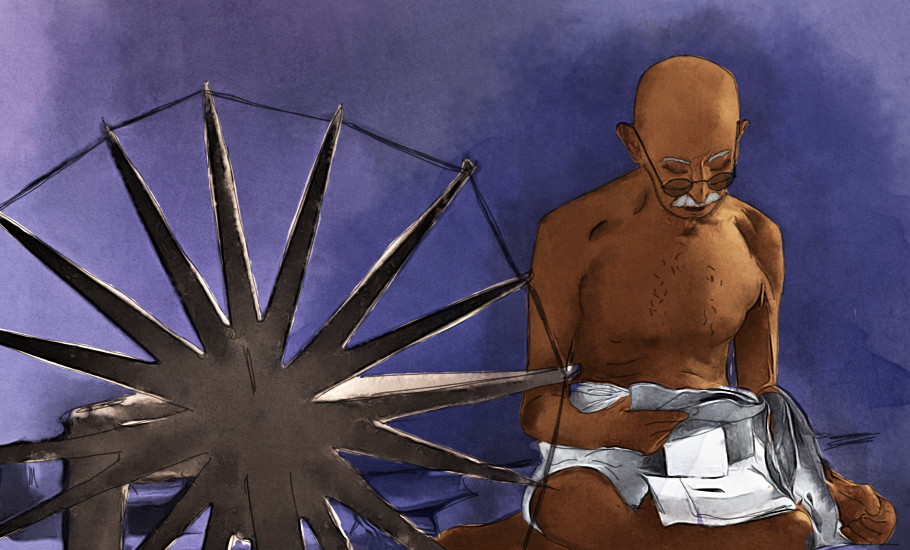

Who doesn’t know the story of a frail man in a loincloth sitting behind the charkha, spinning a revolution. Yet many may still not know in today’s India the reasons that made him dress the way he did or when and where Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi changed into a ‘half-naked fakir’.

It was in 1921 that Gandhi decided to switch from his full dhoti to a handspun loincloth. The change of dress code not only brought a change in how people started looking at the Mahatma but also in the history of India’s freedom struggle itself.

His seditious heart

Gandhi’s sartorial revolution amply demonstrated that seditious clothing could have a far greater impact on public opinion than seditious words, says Peter Gonsalves, professor, Sciences of Social Communication, Salesian Pontifical University, Rome.

“Thanks to the international publicity through photographs and reports, the thousands of satyagrahis who suffered violence at the hands of the British in khadi attire and Gandhi topis provided exceptionally dramatic effect to India’s demand for freedom on the stage of the world,” Gonsalves writes in his book Clothing for Liberation: A Communication Analyses of Gandhi’s Swadeshi Revolution.

His choice gave to clothing — a conventional form of non-verbal communication — a historical, political, economic, social, psychological, cultural and moral significance that had no precedence and has no parallel, adds Gonsalves.

Gandhi believed that though the spinning wheel couldn’t fulfill each and every need of the people, it would at least provide them the means to achieve two basic needs – food and clothing.

“If we want to give these people a sense of freedom we shall have to provide them with work which they can easily do in their desolate homes and which would give them at least the barest living. This can only be done by the spinning wheel. And when they have become self-reliant and are able to support themselves, we are in a position to talk to them about freedom, about Congress, etc,” Gandhi wrote in the Young India.

But has the country achieved what Gandhi dreamt of? Can Khadi be a lifeline to the masses? Is it even profitable? Has Khadi reached the new generation? The answer to all these questions, unfortunately, is no.

Search for pan-Indian attire

When we look at Gandhi’s life, it is clear that he did not take the decision of changing his attire overnight. His autobiography, My Experiments with Truth, elucidates his constant search for a ‘pan-Indian attire’.

From the time he left South Africa for India in 1915, Gandhi started to distance himself from the English style of dressing. At first, he started wearing the traditional Kathiawadi dress – a long coat with strings instead of buttons, a full dhoti, a shawl and a turban, which he later replaced with the now famous Gandhi topi. However, even before embracing the Kathiawadi dress, Gandhi wore a white kurta and dhoti in South Africa as a symbol of mourning, when violence was unleashed against Indian indentured labourers.

“In 1917 he started out on his new quest for a pan-Indian alternative, one that would symbolise his inclusive aspirations for an India that was one, despite her differences in caste, culture, class and creed,” writes Gonsalves.

Because for the British, Gonsalves writes, their attire was not merely a manifestation of superior quality fashion. “It was more importantly a symbol of their self-perception as a superior race. Clothing was their second skin, non-transferable without their consent.”

Gandhi also believed that these foreign clothes were the primary reason why the country’s second-largest occupation – weaving – after agriculture, started to suffer. He called the people to get rid of foreign clothes by burning them. He then urged the people to buy khadi. But he soon realised that most people could not afford to burn their foreign clothes and replace that with khadi.

Khadi’s Tamil connection

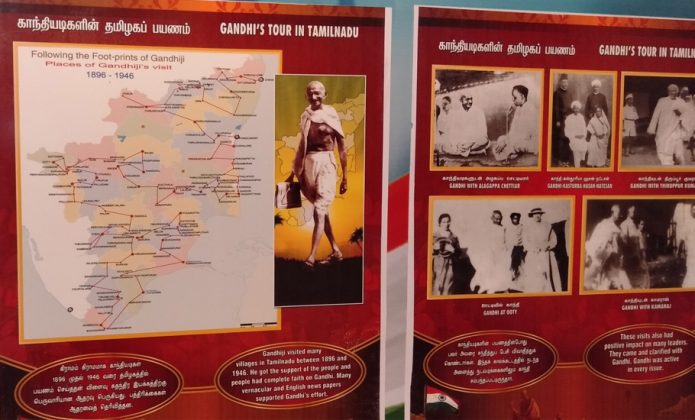

Between 1896 and 1946, Gandhi visited Tamil Nadu 20 times. Five of those visits were to Madurai.

On its part, Madurai has a distinct place in the country’s freedom struggle. The first district committee of the Indian National Congress was launched in Madurai. Again, the state’s first agitation against toddy shops was organised in the temple city where 19 people were arrested. It was here that the Indian flag was hoisted at a temple gopuram, for the first time in the state.

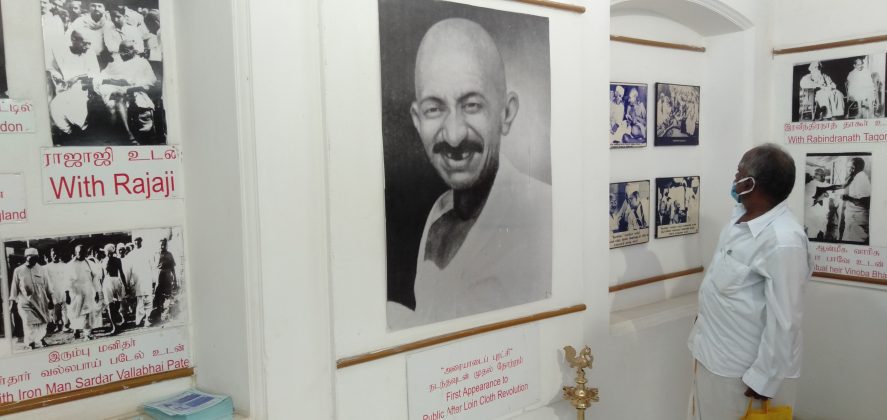

When Gandhi made his second visit to Madurai on September 21, 1921, he stayed in the house of his followers Ramji and Kalyanji. The house, bearing the door number 251-A located in West Masi street, has two floors and Gandhi stayed on the first floor.

It is said that it was during a train trip to Johannesburg that Gandhi read the Unto This Last by John Ruskin and conceived the concept of ‘Sarvodaya’. Similarly, traveling from New Delhi to Madurai, Gandhi was struck by the poverty that made him a “half-naked fakir”.

“On the way [to Madurai] I saw in our [train] compartment crowds that were wholly unconcerned with what had happened. Almost everyone without exception were bedecked in foreign fineries. I entered into conversation with some of them and pleaded for khadi. They shook their heads as they said: ‘We are too poor to buy khadi, it is so dear.’ I realised the substratum of truth behind the remark. I had my vest, cap and full dhoti on.”

After a whole night’s thinking about the the attire of the poor peasant who could afford to wear only a loincloth, Gandhi announced this decision on September 22, 1921:

“I give the advice under a full sense of my responsibility. In order to therefore set the example, I propose to discard at least up to the October 31 [1921] my topi and vest and to content myself with only a loincloth and a khaddar whenever found necessary for the protection of the body. I adopt the change because I have always hesitated to advise anything I may not myself be prepared to follow, also because I am anxious, by leading the way, to make it easy for those who cannot afford to change by discarding their foreign garments (The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi).”

The historic event where Gandhi changed into a loincloth later became a Khadi Kraft showroom.

The aftermath

Despite opposition from some Indian leaders – Dr BR Ambedkar (who said khadi was a ‘symbol of retrogression’), AK Jinnah (who viewed khadi as a ‘symbol of uneducated’) and VD Savarkar (who saw khadi as ‘impotent’) – by and large, it was well-received by other leaders.

“By 1921, all Congressmen were dressed in khadi. The governor of Bombay Presidency, Chittaranjan Das, made khadi the uniform of civic employees, fulfilling in a prophetic manner the desire Queen Victoria had expressed 45 years before – to orientalise the dress of Indian civil servants. The boycott and burning of foreign cloth and the growing network of handspun khadi across India gave a visible face to the Civil Disobedience Movement and altered representations of civility: the civilised person was no longer one who dressed in English clothes, but the one who refused to cooperate with a government that ruled through unjust laws,” Gonsalves says in his book.

Gandhi was so convinced about the uniting potential of the charkha and khadi that he wanted the national flag to epitomise it – ‘for it is through coarse cloth alone that we can make India independent of foreign markets for her cloth’, writes Gonsalves.

Khadi’s relevance today

‘Sarvodaya’ means welfare for all – the Hindi term ‘Sarva’ (for all) and ‘Udaya’ meaning evolution. Thus, ‘Sarvodaya’ is the movement for everyone’s welfare, says Dr R Devadoss, principal and research officer, Institute of Gandhian Studies and Research, Madurai.

“If there is a joint family, there will be a ‘Sarvodaya’. A whole family would be involved in ‘Sarvodaya’ activities like spinning and weaving. But gone are the days. Now, there are no joint families and hence, the ‘Sarvodaya’ philosophy, too, is losing its meaning,” he adds.

According to Devadoss, if 100 students come to learn about Gandhian thoughts, at least two or three of them go back as a changed person. “But that 3 per cent is not multiplying enough. That’s where the problem lies.”

According to Gandhi, Devadoss adds, our duty is more important than our rights. “But it has changed now. The youth is no longer attracted to Gandhian ideology.”

However, it is not only the ideology. Drawing the youth towards Khadi products is equally difficult, says Senthilnathan, secretary, Tamil Nadu Sarvodaya Sangh, Tiruppur.

The Tiruppur wing of the Sarvodaya Sangh once operated as a head office for all the 77 centres across the state. About 15,000 artisans are employed in these sanghs and each centre takes care of its own operations. It was in one such centre in the country where Gandhi came up with the Sarvodaya philosophy. The Sarvodaya Sangh is run by Khadi and Village Industries (KVIC), which operates under the Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

“In order to attract the youth towards Khadi, we are bringing out kurtas and pants. Since these are handwoven, they are expensive as well. Quality-wise too, these clothings look uneven and require additional care while washing such as it may need starch, etc., to maintain its stiffness. Compared to dresses woven on the powerlooms, these materials are quite durable,” says Senthilnathan.

To keep the KVICs running, the Centre and state governments provide 15 per cent commission to them for each product. “So, if a hand-woven towel costs Rs 200, we sell it for Rs 140. Since it is handwoven, per day only two towels can be made. The labour charges come to around Rs 50 per towel. Whereas, in powerloom, 500 towels can be made every day with a labour cost of Rs 5 per towel. So, the price of the towel will be less and since the quality is also good, people do go for it,” says Pandian, a Khadi showroom manager.

On a shaky ground already, the KVIC has been further affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in the last two years. The data by KVIC is worrying. In 2019-2020, the overall production was Rs 2,292.44 crore. In 2020-2021, it came down to Rs 1,904.49 crore. Similarly the sales number stood at Rs 4,211.26 crore in 2019-2020, which came down to Rs 3,527.71 crore in 2020-2021.

However, there is a silver lining in the gross annual turnover. In the previous fiscal it was Rs 88,887 crore but has increased to Rs 95,741.74 crore in 2020-2021.

But that’s not all which is ailing the khadi sector.

To modernise or not

While Khadi focuses on dress materials, bedsheets, pillows, carpets, screens, etc, the village industries are focusing on food products, soaps, incense sticks, furniture and footwear.

Gandhi believed that through Khadi, many can get employment. But that’s no longer the case, laments Senthilnathan.

“We provide training, equipment, raw materials, free maintenance of equipment and labour charges. But even then today’s youth are not coming forward to learn the trade – spinning or weaving.”

In state-run schools, a decade or two ago, there was a course on weaving technology. Students showed interest to learn the trade and there was a constant inflow of artisans. But after the arrival of the IT and ITES courses, the weaving course became obsolete.

Senthilnathan firmly believes the KVIC badly needs an overhaul and should be modernised. But it seems quite impossible.

“Gandhi himself was an opponent to big mills and automation. He believed that modernisation will bring down employment opportunities. But if we don’t modernise (like using new tools in production and adopting new marketing strategies), we cannot stop the attrition rate.”

It’s a Gandhian dilemma and no one knows how to go about it, he adds.

Politically speaking, a senior journalist recently posted on social media that since the Congress has forgotten Gandhi and does not come forward to celebrate such centenary happenings, the leader who dreamt of a ‘Ramrajya’ is literally appropriated by dhoti companies like Ramraj Cotton in Tamil Nadu. It has become one of the leading dhoti brands in the state.

When former IAS officer U Sagayam was the managing director of the state-run Co-optex, Tamil Nadu introduced ‘Dhoti Day’ (January 13, a day before Pongal festival) in 2014, to encourage government employees to wear dhoti. The sale of dhoti increased noticeably that year.

However, such special days mostly continued because of private players like Ramraj Cotton. It came up with a wide range of dhotis for different occasions – temple dhoti, festival dhoti, ‘rough use’ dhoti, marriage dhoti, formal dhoti for office-goers, dhotis for children, etc. It even introduced the ‘Gen Next Velcro Pocket Dhoti’ for youths. As a result, today many, including the highly fashion conscious youths, have embraced dhoti as a fashion statement in Tamil Nadu. It’s true for neighbouring Kerala as well. From politicians to celebs and ordinary citizens, everybody has wrapped their minds around the idea of donning the handloom veshti (Tamil Nadu) and mundu (Kerala).

Many among the Khadi proponents believe that unless the KVIC gets into such robust brand management, there is little hope for khadi, especially outside Tamil Nadu. To put it in Gandhi’s words: “If the Congressmen will put their heart into the work, they will make improvements in the tools and make many discoveries. In our country there has been a divorce between labour and intelligence. The result has been stagnation.”

If there is an indissoluble marriage between the two, the Mahatma had said, the resultant good will be inestimable.