- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Land swap: 5 yrs on, these people regret choosing India over Bangladesh

On July 31, 2015, as part of a historic land boundary agreement (LBA), India and Bangladesh exchanged 162 landlocked islands embedded deep inside the territory of the other country.

Usman Gani was among hundreds of people who had preferred India over Bangladesh five years ago when the two countries attempted to fix a quirk of history scripted centuries ago, ostensibly by a royal pastime. A choice they rue now, claiming their life would have been better off in Bangladesh, which has reportedly taken better care of its nascent citizens. On July 31, 2015, as part of...

Usman Gani was among hundreds of people who had preferred India over Bangladesh five years ago when the two countries attempted to fix a quirk of history scripted centuries ago, ostensibly by a royal pastime.

A choice they rue now, claiming their life would have been better off in Bangladesh, which has reportedly taken better care of its nascent citizens.

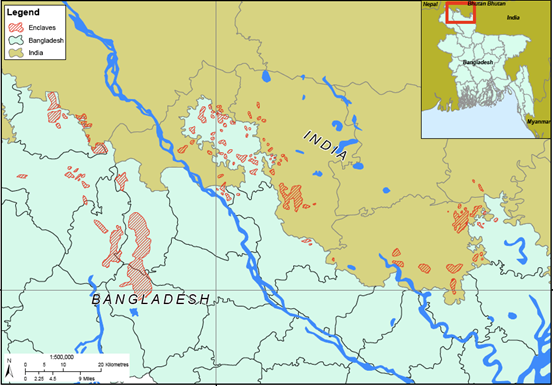

On July 31, 2015, as part of a historic land boundary agreement (LBA), India and Bangladesh exchanged 162 landlocked islands embedded deep inside the territory of the other country, ending a seven-decade-old complex land dispute.

The legend goes that this unique landmass was formed in the 18th century out of a series of chess games between the Maharajas of Cooch Behar, now in India, and Rangpur, now in Bangladesh.

They would wager villages on their chessboards and that led to the kings owning areas within each other’s territory.

What LBA did?

After India’s independence, as boundaries were drawn haphazardly, these enclaves became part of one country while remaining within the borders of the other.

The LBA provided for exchange of these enclaves and allowed the people living there to make a choice whether to be part of India or Bangladesh.

All the 14,856 people living in 51 Bangladeshi enclaves that had become part of Cooch Behar district in West Bengal opted to take Indian citizenship, while 921 people from the 111 Indian enclaves that had been handed over to Bangladesh left behind their ancestral homes to be in India.

“Leaving behind all our immovable properties, we came here to remain in India. We had complete faith that our government would suitably rehabilitate us, as was promised,” says Gani.

Five years down the line, Gani, like many in these nascent Indian territories, is completely disillusioned. According to him, most of the promises made to them are yet to be fulfilled.

“Now that the government has completely failed to rehabilitate us, at least it should send us back to Bangladesh, where we left behind our properties believing the false promises made to us,” stated Gani, who is now trying to eke a living as an Ayurvedic practitioner.

The new India

A cursory visit of the former enclaves that have become part of India such as Paschim Bakalirchara, Purba Mashaldanga, Madhya Masaldanga, etc. or settlement camps in Haldibari, Mekhliganj and Dinhata, will however belie the discontentment.

Newly laid paved roads, electricity connection, primary schools, solar-powered irrigation pumps, residential apartments that have come up in the area give it an apparent look of prosperity and progress. Beneath the veneer however lies the discontentment.

The residents often take to the streets alleging they have not yet received land rights, adequate rehabilitation packages and job opportunities.

“Almost all the residents of this former Bangladesh enclave have no other option but to solely depend on farming for their livelihood as there are not enough alternative employment avenues,” says Saddam Hossain of Madhya Mashaldanga.

His entire 8-member family depends on the 20 bighas (In West Bengal 1 bigha is equal to 14,400 square feet) of farmland for which they have no proper document.

In the absence of valid land documents, he says, people were facing a lot of hardships. “We cannot take housing or farm loans against the land. We cannot also buy or sell properties,” says Hossain, a political science graduate.

“The temporary land deed given to us is also full of errors. For instance, we own 12 bighas of land, but on paper there is only mention of three bighas,” says another former enclave dweller Jainal Abedin.

Many educated youths like Hossain and Abedin also complain about lack of job opportunities for them, pointing out that the Bangladesh government rehabilitated many young erstwhile enclave dwellers in police and other security forces.

Left everything, got little

The problem is more acute for the 921 people who had migrated from the former Indian enclaves in Bangladesh to be part of India.

Last month, after a long wait, they have each been given a key to a two-room flat, which has given them a roof over their head, but no provision has been made for their livelihood yet.

“We had 12 bighas of land in the then Indian enclave in Bangladesh’s Kurigram. We used to grow jute and paddy on nine bighas, whereas on rest three, there were betel nut plantations. The government discouraged us from selling the property, saying we would be suitably compensated,” says Mrinal Barman, now a resident of Dinhata rehabilitation camp.

“Our decision to shift to remain in India has made us destitute with no land or employment. After coming here, I was forced to do menial jobs as a daily wager. But the lockdown has taken away even that job. Now, I am completely unemployed, sustaining on the ration provided by the government,” Barman says.

He lives with his wife in the camp. “Both my parents died after coming here, failing to cope with the new lifestyle,” Barman says.

Gani, who has shifted to Cooch Behar with his five-member family, endorsed Barman’s view.

“They (government authorities) just dump us in these newly built flats without making any provision for our livelihood. On top of that they have now installed an electric sub-metre in our flats. How can we pay the electric bill when most of the residents here do not have any earnings?” Gani asks.

Several petitions to local authorities and even protests did not improve their situation, the residents say.

Issues resolved, says minister

West Bengal minister for North Bengal development Rabindra Nath Ghosh, however, claimed that most of the rehabilitation issues of the former enclave residents had been resolved.

“There had been some issues with the land documents that have been sorted out. As for the employment opportunities, we cannot give any preferential treatment to the youth from the (former) enclaves. But we are arranging skill-development training to help them get jobs,” he says, a claim strongly refuted by the residents.

As for the land demand of 921 migrants, the minister says that that could not be fulfilled. “Where is the land to give them? Not a single resident of the then Bangladeshi enclaves migrated to that country after the LBA was implemented. So there is no left over property to be disbursed among those who have migrated to India,” he says, offering no solution.

NRC threat

Kirity Roy of Masum, a civil rights organisation that has been highlighting the issue of these erstwhile enclaves, also debunked the minister’s claim.

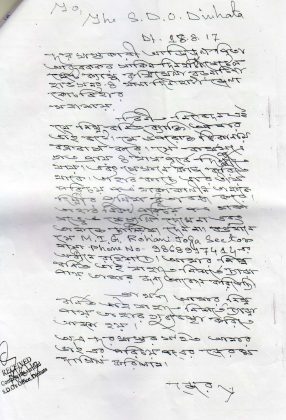

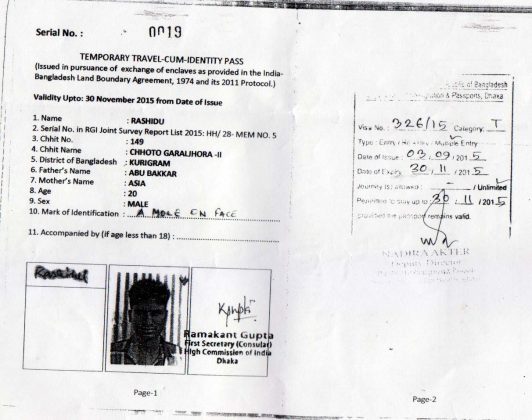

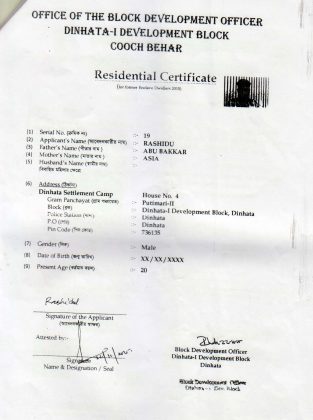

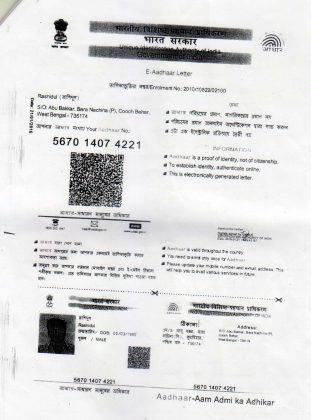

Roy says due to the government’s apathy these people have lost whatever little they had before. “They have no proper land rights and even there is no clarity on their citizenship, which leads us to question what will happen to them if the National Register of Citizenship (NRC) is implemented in the state,” he says, citing an example of Rasidul Islam.

Islam had opted for Indian citizenship although his parents decided to stay back in their ancestral village of Burungamari in Kurigram district of Bangladesh. He was issued Aadhaar and ration cards and also a voter ID, just as issued to other former enclave residents.

All these documents proved nothing three years ago when he migrated to Delhi for a job.

Delhi Police arrested him on August 18, 2017 from Dwarka area and subsequently he was imprisoned for three months. Later, Islam along with 35 other suspected illegal Bangladeshi nationals were sent back to Bangladesh.

“There is no guarantee that other former enclave dwellers will not meet the same fate in future,” Roy says.