- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Sports

- Features

- Health

- Budget 2024-25

- Business

- Series

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - India-Canada ties

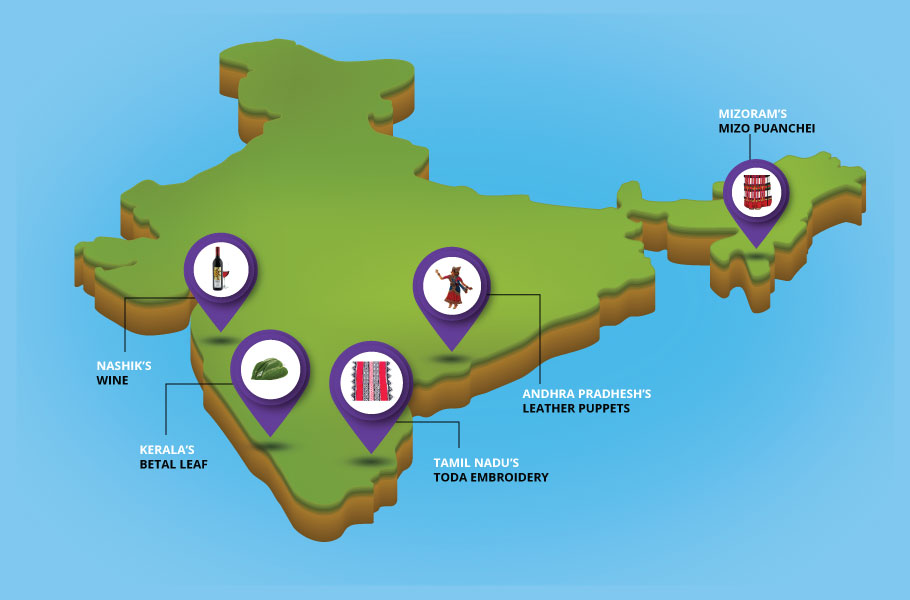

India's traditional products need more than just GI tags

Dalavai Kulayappa, a fourth-generation leather puppet maker from Nimmalakunta village in Anantapur district, is unsure about the future of the craft. Clearly, the Geographical Indication (GI) tag has not helped a lot of artistes in India, who keep centuries-old tradition alive, market their products.

When Andhra Pradesh’s leather puppetry was granted geographical indication (GI) tag in 2008, the makers thought the honour would give their vocation an impetus. But today, Dalavai Kulayappa, a fourth-generation leather puppet maker from Nimmalakunta village in Anantapur district, is unsure about the future of the craft. “I learnt making these puppets from my father, just like how he...

When Andhra Pradesh’s leather puppetry was granted geographical indication (GI) tag in 2008, the makers thought the honour would give their vocation an impetus. But today, Dalavai Kulayappa, a fourth-generation leather puppet maker from Nimmalakunta village in Anantapur district, is unsure about the future of the craft.

“I learnt making these puppets from my father, just like how he had been trained by his father,” he says. “My son who is almost eight is learning it, but I am not sure if he will continue the family vocation. I struggle to make even ₹2-3 lakh a year now.”

Leather puppetry, which uses the hide of goat skin, has its roots in the ancient art form of ‘tholu bommalatta’, a form of puppetry that dates back to the third century. The craft form is among hundreds, including lamp shades, wall hangings and paintings, made in the nondescript but bustling village in Andhra Pradesh.

While the village has produced several extraordinary artistes and Kulayappa himself is a national award winner and a UNESCO awardee, the struggle to keep the art alive is real for him and the 300 artistes in his village.

“We are not a very literate group and knowing the art form alone is not enough for us to survive in today’s age of competition,” Kulayappa rues.

In spite of training programmes organised by the Ministry of Textiles, he says there is no market for their products.

“Even within Andhra, the market is poor. So how do we boost our exports for an outside market? A traditional craftsperson will only know the craft, but very little about marketing or sales,” he points out, and hopes that the government would help them in this regard.

It is a similar case in neighbouring Tamil Nadu, where a group of tribal people in Nilgiris making Toda embroidery, known popularly as pukhoor, are struggling to find takers, a good six years after the craft got GI tag in 2013.

The embroidery form which is said to be several centuries old, has been kept alive by the Toda tribal group in the Ooty hills. From shawls, ladies’ bags to wall hangings and table mats, the embroidery is made using a combination of red, black, white and blue coloured threads on a white cloth.

Sheela Powell, founder, Shalom, a social enterprise working with around 1,000 tribal women by helping them market their work, says, “The GI tag has been like Agmark, nothing more. When we take these outside to markets like Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai, not many know how this is unique. It is really a struggle to get them a fair price for their work.”

An identity for a long standing tradition

The geographical indication (GI) tag is given for products from a specific location or region, acting as a kind of certification that the product possesses certain qualities and is made as per traditional methods. It gives the products a unique identification and aims to boost its market through uniform pricing and by improving export prospects.

India, a member of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), came up with the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act in 1999 and it came into effect in 2003. Darjeeling Tea was the first product to receive the tag in 2004-2005 and as on date, 355 products have received the tag.

Also read: Tamil Nadu’s Palani Panchamirtham, Kerala’s Tirur betel leaf get GI tag

It is given by a registry which scrutinises applications based on various parameters.

Groups or societies can apply for GI tags for products which are historical and are at least a 100 years old. The application should specify the uniqueness, along with proofs of research and gazetteer details to corroborate the historicity, expert opinions, uniqueness of its features, supported by relevant lab reports and details of the entire method of production.

An important consideration for the tag is the benefit it has to society through its utilisation — it could be the medicinal value or health benefit, like in the case of the Erode Manjal, a type of turmeric grown in Erode.

There are five categories of geographical identification — agriculture, food products, manufactured, wine and spirits and handloom and handicrafts.

“The GI Registry grants the tags after a careful scrutiny of the application,” says Chinnaraja G Naidu, deputy registrar of Geographical Indications.

On the concerns regarding the GI tags, he says that the registry is ensuring that the word about GI tags goes around for the benefit of the producers and customers.

“It is important for them to reach out to the market because GI tags provide the products an acknowledgement and certification of its historicity, cultural significance and advantage of uniform pricing and better prospects for exports,” he says.

“We are protecting the wisdom that our forefathers have passed on to us through the tag. Their trust that it will be preserved in its original form is converted into a commercial product. The tag is given to a group and not to an individual. It is applicable only for the particular place and for products made with the recognised specifications,” he explains.

Recently, GI tags were awarded to a range of products across the country — Odisha Rasagola, Dindigul locks, Kandangi sarees and Palani Panchamritham (a prasadam or religious offering) from Tamil Nadu. The Mizo Puanchei, a colourful shawl from Mizoram, and Tirur Betel leaf from Kerala too received the GI tag.

Naidu adds that in the case of the Tirupathi laddoo or the Panchamritam, the recognition has been for the food products and not for the religious aspect.

The success stories

Once upon a time, Madurai used to be famous for its Sungudi sarees, with over a 600-year-old history characterised by the knots hand-woven by around 50,000 weavers. But a census taken soon after the Sungudi saree received GI tag in 2005 revealed that there were just five weavers!

AK Ramesh, president, Madurai Sungudi Weavers Association, says, “Those who continued weaving were already in their 80s. So we began training people with the help of the Ministry of Textiles and the Craft Council of India and have managed to increase the number of weavers specialising in Sungudi to 20 now.”

Ramesh says the GI tag boosted their motivation to reboot their vocation. “At a convention held recently in Geneva too, we sent a couple of samples to be displayed. We aim to increase the number of weavers to 50 and 100 in the coming years,” he says.

The weavers are also giving insights to designers from the National Institute of Fashion Technology in the uniqueness of their weave to spread the word.

At Nashik valley in Maharashtra, wine tourism has increased two-fold after the GI tag was granted in 2010. On weekends, over 50,000 wine tourists throng the wineries — there are over 40 big players in the business. The valley also contributes almost 80 per cent of the wine production in the country.

“We wanted to use the GI tag as a unique tool to promote our product and we soon participated in international exhibitions in Thailand and in Europe, where the European Union has supported us. We have visitors from abroad and from across India every weekend on wine tasting trips, propelling the business through a steady wine tourism,” says Pradeep Pachpatil, proprietor, Soma Wine Village, Nasik.

Lack of awareness, duplication and GST defeat the purpose

The other issue is that despite getting a GI tag, the market is flooded with several duplicates that claim to be Sungudi, and these include batiks and bandhinis, hand-printed sarees.

Ramesh says pricing issues add to the loss. “A handloom Sungudi can range anywhere between Rs 2,000 and Rs 20,000 and a powerloom one is in the Rs 2,000-5,000 bracket. There are imitations priced at Rs 500 and Rs 600 in the market sold as Sungudi and many of the buyers who come to us wonder why they should buy from us when they get sarees for one-tenth of the original’s price.”

Sanjai Gandhi, nodal officer, Geographical Indications Products (registration and implementation), Tamil Nadu and president, Intellectual Property Attorney Association, says that the logo allotted to the products is grossly underutilised.

“The departments like the concerned handloom department in the state should take action against those making false claims,” he demands.

Acknowledging the threat posed by imitations, Naidu says that the responsibility of ensuring that the products with GI tag is not duplicated lies with the community.

“We understand that the significance of the tag is only understood by 1 per cent of the population. We have recommended that a chapter on GI is included in the school curriculum and the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) is considering the proposal,” he adds.

The Cell for IPR Promotions & Management (CIPAM), an arm of the department of industrial policy and promotion (DIPP), is also working on training and awareness programmes in educational institutions to identity them.

“100 such projects are being carried out and the focus is more on the upliftment of farmers and weavers, along with craftspersons,” explains Naidu.

Gandhi also says that relaxation of Goods and Services Tax for individual users of GI tag will ensure that the products thrive. “Or else, the GI tag products will be mere exhibition items, rather than ensuring continuance of tradition.”

He explains that once the group or society gets a GI tag registered, individual authorised users of the tag apply for it.

“The GST rates should be relaxed for them. Today, handicrafts like Swamimalai bronze lamp, Nachiarkoil Kuthuvilakku (Nachiarkoil Lamp), Thanjavur art plate and Thanjavur paintings — collectively known as Tanjore Swami works during the British period thrive because of their export to countries like Singapore and Malaysia. We need to come up with policies that waive off GST rates to ensure they survive,” he says.