- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How Wajida Tabassum explored desire, debauchery of Hyderabad’s aristocracy

Lascivious nawabs, lustful begums and wily servants were recurring figures in the short stories by iconic Urdu writer Wajida Tabassum (1935-2011). With fearless honesty, she bared the desires and debauchery of Hyderabad’s aristocracy in the mid-twentieth century, depicting marriages fraught with unfulfillment and strange customs, and forbidden passions that stirred the soul of...

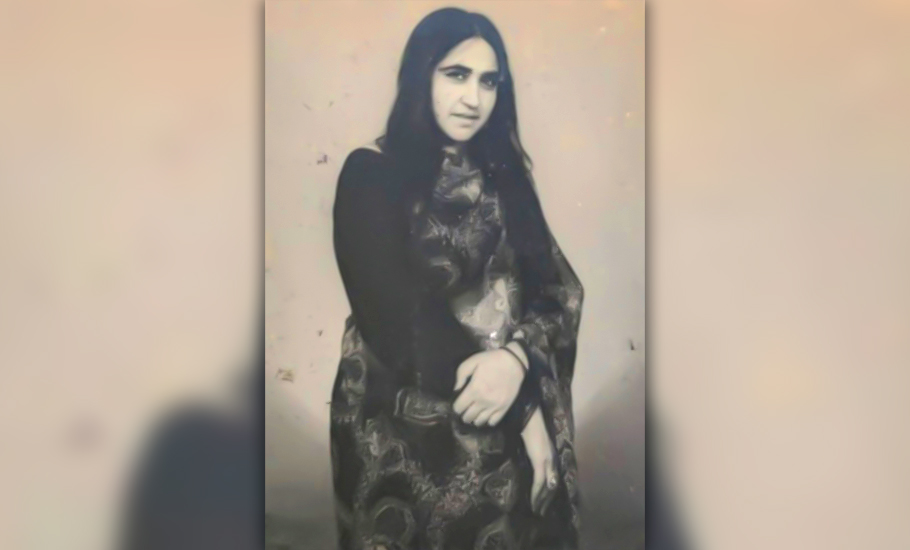

Lascivious nawabs, lustful begums and wily servants were recurring figures in the short stories by iconic Urdu writer Wajida Tabassum (1935-2011). With fearless honesty, she bared the desires and debauchery of Hyderabad’s aristocracy in the mid-twentieth century, depicting marriages fraught with unfulfillment and strange customs, and forbidden passions that stirred the soul of her characters.

Tabassum, an unsung icon whose works are not as readily available in English as those by her male counterpart Saadat Hasan Manto, was unafraid to delve into taboo subjects and challenge the social conventions of her time. Her stories, both powerful and poignant, bring to light the complex and often contradictory nature of human desire, captivating readers with their vivid depictions of forbidden passion. More importantly, they challenged patriarchal norms that sought to control, repress and shame women’s sexuality.

In the annals of Urdu literature, Tabassum remains a figure at once celebrated and controversial, like Manto, for her unflinching exploration of human sexuality and relationships — lauded and reviled in equal measure. Her frank portrayal of the realities of the society she lived in, despite facing the scathing criticism of the cultural gatekeepers of her time, had earned her the epithet of ‘female Manto.’ While her critics dismissed her as they felt that she crossed the limits of decorum and decency, others hailed her as a sahib-e-asloob, a writer with a distinct style.

Tabassum, who also penned verses and songs, wrote 27 books. Her masterful short stories, like those by avant-garde Urdu writers Ismat Chughtai (1915-1967) and Qurratulain Hyder (1927-2007), draw us into a world of complex social hierarchies, where the veneer of respectability is often shattered by the baser instincts of human nature. Her characters are crafted with a depth and nuance that is both mesmerizing and haunting, their secret longings and fears laid bare in exquisite detail.

For decades, her literary works have remained inaccessible to English readers, except for a few scattered translations here and there, creating an insurmountable barrier for those who yearn to experience the depth and beauty of her writing. In Sin: Stories by Wajida Tabassum (Hachette India, 2022), Pakistani writer Reema Abbasi takes a step towards redressing this literary injustice.

Sin features Tabassum’s 18 intrepid stories, translated by Abbasi, that revolve around the theme of the ‘deadly sins’ — lust, pride, greed, and envy. Tabassum’s writing shines light on the realities of middle-class compulsions and the depravities indulged in by the social elite, delving deep into themes of impotence, powerplay, betrayal, and abandonment that serve as haunting metaphors for the downfall of the nobility, as Abbasi underlines in her introduction to the collection.

In the traditional South Asian societies, Abbasi writes, women are expected to uphold strict standards of purity and remain trapped between societal expectations of rapture and revulsion. Tabassum’s writing seeks to break down these societal confines and give women the right to possess and indulge in their primal desires. Her work challenges the orthodox notions that imprison women, forcing them into a lifetime of self-denial. Her protagonists go against the grain, claiming and indulging in their base desires. What others view as sins, Tabassum portrays as salvation for her women characters. Tabassum’s work stands as ‘an untouched jewel of Urdu literature’ that captures the power of the subliminal and subconscious with precision and subtlety, and challenges conservative notions of purity and self-denial.

One of Tabassum’s stories, ‘Hor Upar!’ (Up, Further Up), included in Sin, faced heavy criticism for its unapologetic depiction of a Begum’s revolt against her husband’s drunken sexual escapades, with maids in the palace. The story portrays the Begum as spurned and lustful, appointing a young boy to massage her. As the story progresses, his hands move upward, causing a slow rise to the crescendo of desire, subtly resembling one in Chughtai’s ‘Lihaaf’. Despite the threat of censure, the Begum refuses to acknowledge it and continues to indulge in her desires.

In her stories, Tabassum drew a lot on her experiences, the life around her. Born in Amravati (Maharashtra) on March 16 (1935), she lost her parents as a little child. She moved to Hyderabad with other family members after the Partition, where she graduated from Osmania University with a degree in Urdu language. At the age of 20, she began writing stories in the Dakhini dialect in the backdrop of the aristocratic social life of Hyderabad in the 1940s. She married her cousin Ashfaq Ahmad, who worked in the Indian Railways, in 1960. After Ashfaq retired, he published all her books. Later, they settled in Bombay and had five children; four sons and one daughter. In her later years, Tabassum suffered from arthritis, but continued writing until she withdrew from the scene and led a secluded life till she passed away on December 7, 2011.

Also included in Sin is an essay, ‘Meri Kahaani’ (My Story), written in 1959, in which Tabassum writes about her life since the time she lost her parents. Her mother came from a royal family, and her father was a prominent lawyer in Amravati, who earned millions. But he lost all his money, and when he died, the family plunged into penury. A voracious reader since childhood, Tabassum would read every word she could find, from magazines like Shamaa, Ariyavarat and Kaambyaab, to torn pages of newspapers used to wrap groceries. Money was ‘a lofty reverie, like a gulp of the sun’ and Tabassum’s desire to go to markets, explore bookshops and buy literature ‘caved’ before the family’s meagre means. Stories, she writes, became her saviours that carried her ‘out of a murky hole to a meadow.’ They became receptacles of her ‘hushed sadness’ and the ‘storm’ of her emotions.

Some of Tabassum’s books were adapted into popular movies and TV serials. Her controversial story, ‘Utran’ (Cast-offs), was published in an eponymous collection in 1975. Adapted into a popular soap opera on Indian television in 1988, it delves into the complex dynamics of unequal female friendships and the manipulation of sexuality. The story revolves around two childhood friends, Shahzadi Pasha and Chamki, who are acutely aware of the stark difference in their social status: while Pasha comes from a wealthy family, Chamki is the daughter of Pasha’s wet-nurse.

The plot takes a dramatic turn on the eve of Pasha’s wedding when Chamki, seething with resentment over Pasha’s privileged life and treatment of her, decides to seek revenge by sleeping with Pasha’s groom. Following the wedding, Chamki relishes her retaliation, taunting Pasha with the words, “All my life, I have lived with your cast-offs, but now you too will forever live with something I have used.” The story concludes on a sombre note, with Pasha’s life forever altered by Chamki’s act of vengeance.

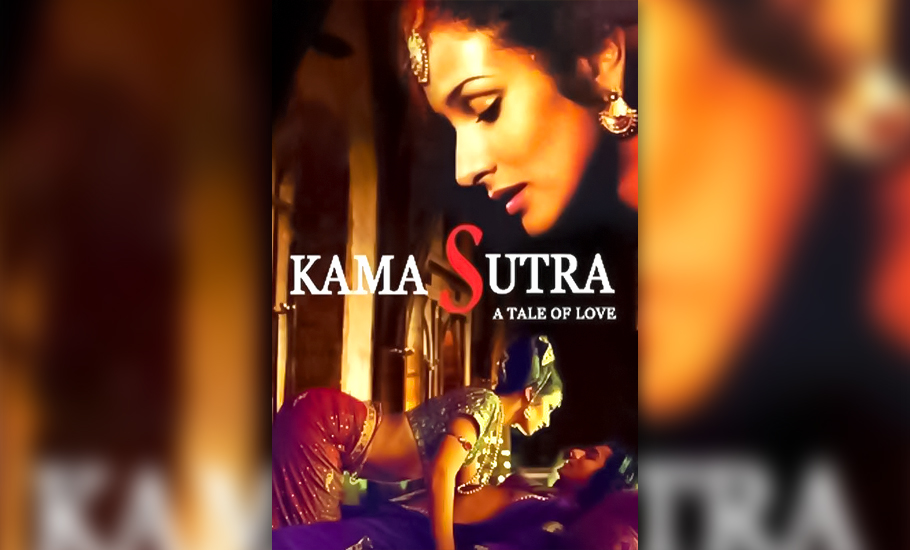

‘Utran’ has been translated into English and featured in several anthologies. It was also adapted into a popular soap opera in 1988, but it is perhaps most widely recognized for its adaptation by Mira Nair for the first half of her 1996 film Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love. The film’s characters, Indira Varma and Sarita Choudhury, are based on Chamki and Shahzadi Pasha, respectively.

The movie explores similar themes of power dynamics and sexual manipulation; the adaptation helped introduce Tabassum’s work to a broader audience. Nair had noticed the story when it was reprinted in English translation as part of an anthology of 20 short stories, Such Devoted Sisters, in 1994; she had subsequently used it for the script she co-wrote with South African playwright and screenwriter Helena Kriel.

Tabassum’s boldness and nonconformity were met with ferocity by her critics; frenzied mobs torched the offices of her publishers and she also faced tremendous opposition from her own family and community, who saw her work as semi-erotic work. When ‘Utran’ was published, the literary world was aflutter, with her critics alleging that Tabassum had committed a grave offense by misusing the Hyderabadi and Dakhini dialects in her work. They argued that her intent was not to celebrate the city’s culture but rather to sensationalize it for the sake of her stories. There were death threats, too, but she continued to write, displaying astonishing nerve and rare determination.

In the preface to a later edition of her first collection of stories, Shahr-e Mamnu (Forbidden City), Tabassum wrote: “‘Torment is universal. It does not spare a soul. Why should you worry and weep over it, or declare it to the world? When you tell the world about it, you erase everything learnt from it and gained through it?’ These lines, and Dagh Dehlvi’s verse, ‘Shirkat-e-gham bhi nahin chahti ghairat meri… (My pride does not want a consoler)’ stared at me before I wrote My Story (Meri Kahani). I spent endless hours wondering whether my circumstances should be disclosed. In doing so, do I risk a loss? Did it ever return anything? Then I thought, I must write regardless of the perils. As for ‘shirkat e gham’, my grief wore a shroud because I knew the futility of laying it bare. My sadness has become my past. I want to tell my tale because you questioned my writing. My life does not shame me.” This underscores that Tabassum recognized the potential costs of speaking out, but ultimately chose to do so in order to assert her own voice and tell her own story — and of several others.