- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

COVID-19 stigma: Indians have distanced themselves from rationality

A society devoid of rationalists will continue to invoke superstitious beliefs and practices. This gets amplified when top political leaders attach everything to mythology and vedas and puranas.

In the first week of April, 19-year-old Revathi’s (name changed) visit to a primary health centre (PHC) made her a target of angry neighbours and strangers in Madurai district’s Ellumalai village. Revathi was experiencing headache and cough. The PHC doctor told her it was a normal cough and gave some medicines. “But somebody took a picture of us in the PHC and circulated it...

In the first week of April, 19-year-old Revathi’s (name changed) visit to a primary health centre (PHC) made her a target of angry neighbours and strangers in Madurai district’s Ellumalai village.

Revathi was experiencing headache and cough. The PHC doctor told her it was a normal cough and gave some medicines. “But somebody took a picture of us in the PHC and circulated it among villagers saying my daughter has acquired COVID-19,” says the father of the 19-year-old.

Since the villagers made it very clear that they would not allow the family to enter the village, Revathi and her family could come home only after she tested negative for coronavirus in a government hospital in Madurai.

Somewhat similar to Revathi’s experience, a passenger travelling on Chennai-Guwahati Express recently became a victim of collective panic and vigilantism. His co-passengers raised an alarm and informed railway officials at Andal station in West Bengal when they found him coughing. The passenger was forced to get off the train as a team of doctors took him to a hospital in Asansol, only to be released later.

Police stations have been flooded with frantic phone calls from residents, seeking protection from coughing and sneezing neighbours.

Many with recent travel history found themselves at the receiving end of ostracisation by neighbours and strangers, even when they posed no actual threat or exposure to COVID-19.

“People looked at me with suspicion. Even strangers started flooding me with threat calls and messages, saying my ‘crime’ shouldn’t go unpunished,” says a young woman from Assam who was swamped by anonymous calls and WhatsApp messages after rumours spread that her number was “traced” to a list of attendees from Assam linked to a religious congregation in Delhi.

“I have not visited Delhi in more than a year now. I used to live there before moving back to Assam last year. In any case, the administration and police must answer how the list was made public,” she says.

Despite public health officials globally warning against stigmatising minority groups, Indians, especially Muslims, across cities faced severe attacks, with officials and sections of media putting the entire blame for spreading the virus on one Islamic group.

While many ruling party leaders and TV channels have consistently linked the spread of COVID-19 to imaginary “human bombs” and “corona jihad”, the number of such attacks have increased. The coronavirus pandemic has also unleashed racist attacks on people from northeastern states.

“This is extreme hate and prejudice. We have been stigmatised as carriers of coronavirus. This otherisation has no end. It doesn’t take them long to call us ‘chinkis’ and ‘Chinese’ and now ‘coronavirus’,” laments Bangalore-based Runeeta.

While many Indians see such racist attacks and religious hate as “acts of ignorance and poor knowledge of how the virus spreads”, Runeeta believes such prejudice runs deeper among the middle class and elite Indians.

“How can we expect better, rational behaviour from poor villagers and unlettered people when the educated ones spread and perpetuate such bias?”

Stigma distanced people from hospitals

Runeeta’s fears don’t seem unfounded. The fear of ostracisation has led many to either not report their travel/contact history and symptoms or evade quarantine and isolation.

“After the outbreak, villagers have stopped visiting PHCs for even headache and cough. They fear they will be tagged as coronavirus positive,” says a health worker working in a PHC near Samayanallur in Madurai.

So much so, that sanitary workers refrained from going to work in Thoothukudi government hospital, as health workers and even doctors are facing stigma and discrimination. Many frontline health and essential services’ workers across cities have faced ostracisation and eviction notices from landlords and residents’ welfare associations.

Many in quarantine, including those who haven’t tested positive, have been targeted as several state governments violated medical ethics codes by publicising their address details.

In many areas, even the dead were not spared. The cremation of Akhay Raul in Bengal’s Ghatua village (East Midnapore district) was disrupted on March 26 evening following rumours that the 23-year-old died of COVID-19. Raul, however, had committed suicide. The body could be cremated only after police intervention.

Similar public hostility was witnessed during the cremation of the state’s first COVID-19 casualty, a 57-year-old resident of Dumdum in Kolkata March 23.

In several villages across states, people are opposed the setting up of quarantine centres.

A man was killed in Talibpur village in West Bengal’s Birbhum district in a clash between two groups over the setting up of a quarantine centre at a village school nearby on April 4.

But what has left everyone shocked is the behaviour of some top government officials.

“The fact that some top bureaucrats chose to hide the travel history of their sons and daughters says a lot about the deep-seated fear and prejudices even among the educated,” points out Runeeta.

Social distancing and prejudices

While fear and stigma are intrinsically linked to any infectious disease, it is difficult to say if Indians are scared more of the disease or let go their biases.

The fear of being socially marginalised and stigmatised as a result of a disease outbreak has in the past too caused many to deny clinical symptoms. Many refrained from seeking timely medical care. This is precisely why public health experts have been urging governments and media not to attach locations or ethnicity to coronavirus.

It was common for viral diseases to be associated with places or regions where the first outbreaks occurred — such as Asian flu and Japanese encephalitis, etc. But the World Health Organization in 2015 issued guidelines to stop this practice to reduce stigma as well as fear and anger towards particular countries, regions or their people.

But it seems Indians, already living socially accepted segregated lives — based on caste and class — found a new excuse in coronavirus to justify practices like untouchability.

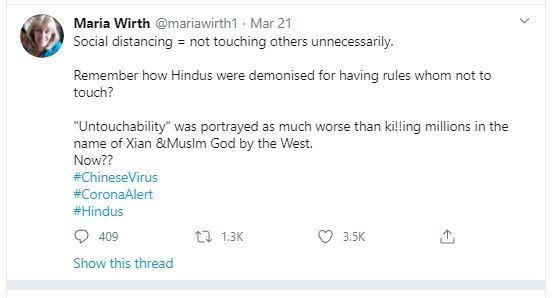

A Twitter user, Maria Wirth, who is followed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, recently linked social distancing to untouchability.

While many called out her blatant attempt at legitimising the caste system and the unjust social stratification that exists in India, staunch Hindu supporters defended her vociferously on social media.

“Ideally, she should be charged under SC/ST Act. But it’s amusing to see how Muslim-haters in India gloat in support from White Hindus like Wirth and (David) Frawley. They are not so accommodating of westerners who point out policy flaws in Indian governance besides oppressive practices,” says Namrata. The 21-year-old Delhi University student finds it amusing when “Hindu nationalists” see anyone who criticises the government as conspirators who want to discredit India.

Bring back the rationalists

Kolkata-based educationist Arundhati Roy-Chowdhury believes such prejudiced practices are steeped in our society. “Even educated people resort to superstitious practices that are related to religion.”

There are people, she adds, who still believe in hiding life-threatening diseases. “Families still talk about diseases like cancer in a hush-hush tone. Not to mention diseases like HIV/AIDS. The stigma is deep-rooted.”

Rational consciousness is yet to develop among ridiculously superstitious Indians.

“That is why when the PM urged citizens to beat pots and plates to thank healthcare workers, everybody, including government representatives, turned it into a ‘Go Corona Go’ show. They seriously believed lighting lamps and mobile phone torch will drive the coronavirus away.”

Roy was referring to WhatApp messages and videos claiming “coronavirus does not survive in hot temperatures, as per research by NASA”. Such messages started circulating on social media immediately after Modi’s 9 am video message on April 3, urging Indians to turn of lights on April 5 at 9 pm for nine minutes and light up candles, lamps or flashlights to display a collective spirit of the country to defeat the novel coronavirus.

Even cardiologist KK Aggarwal, a former national president of the Indian Medical Association, justified the PM’s call to light lamps and candles with a strange video, which Scroll described as a “cocktail of pseudoscience and so-called yogic principles”.

“There is no space for rational thinking and rationalists. We have witnessed the murders of rationalists like MM Kalburgi, Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare,” says a Bangalore-based journalist who had to face online abuse for her rational views that were considered anti-Hindu by trolls.

A society devoid of rationalists, she adds, will continue to invoke superstitious beliefs and practices. This gets amplified when top political leaders attach everything to mythology and vedas and puranas. “Like Lord Ganesha’s plastic surgery or cow urine as miraculous cure for diseases,” she sighs.

Karimganj-based physics professor Nirmal Kumar Sarkar, a member of Science and Rationalists’ Association of India, agrees that the shrinking space for scientific temper in India is worrisome.

“Recently, Barak Valley in Assam was agog with rumours that Lord Shiva had descended on earth to save everyone from coronavirus. This was spread through a video showing a pestle standing straight on flat stone mortar without support. People claimed the phallic-shaped pestle signifies Shivalingam.”

Some people, Sarkar adds, happily believed the video ignoring the physics behind the trick.

“Every educated person is literate, but every literate is not necessarily educated.”