- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Sports

- Features

- Health

- Budget 2024-25

- Business

- Series

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - India-Canada ties

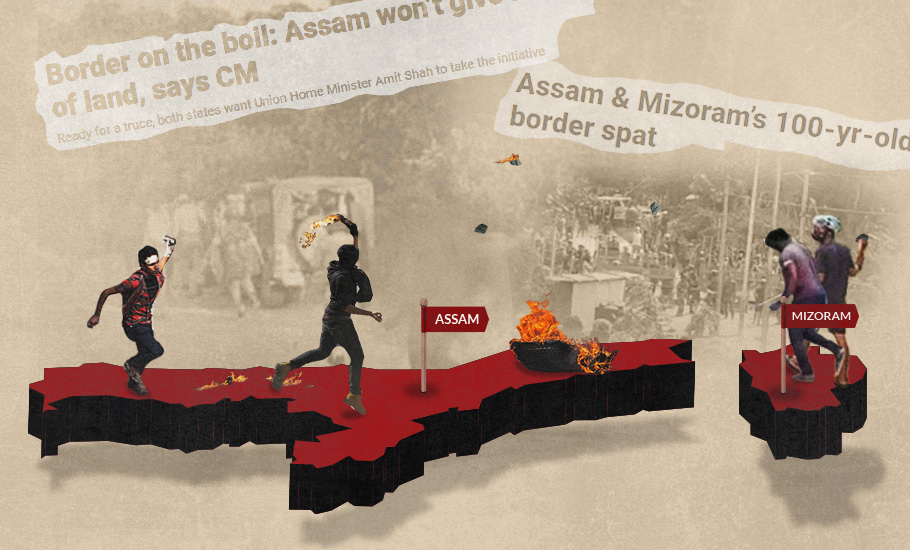

Assam-Mizoram border clash tatters BJP’s unity bid in Northeast

The Assam-Mizoram police clash was the first major test for Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma after he took over the reins of the state in May this year

Armed personnel in olive-green fatigue from Mizoram Police’s India Reserve Battalion took position on a hilltop in Vairengte on Monday evening. Their location was not very far from Indian Army’s Counter-Insurgency and Jungle Warfare School. Only that this time the men in uniform were not there for any guerrilla warfare training. They were there for real combat. “Paanch minute time deta...

Armed personnel in olive-green fatigue from Mizoram Police’s India Reserve Battalion took position on a hilltop in Vairengte on Monday evening. Their location was not very far from Indian Army’s Counter-Insurgency and Jungle Warfare School.

Only that this time the men in uniform were not there for any guerrilla warfare training. They were there for real combat.

“Paanch minute time deta hai, chala jao (Leave the place within five minutes or face the consequence,” one of the armed personnel shouted in a colloquial Hindi, training his gun on a group gathered on the foothills near Lailapur.

What followed next horrified the nation and made news headlines across the country. Six people were left dead and 41 others wounded in a rare incident of police personnel of an Indian state opening fire on their counterparts from a neighbouring state over a boundary dispute. Five of the dead were policemen from Assam. Among the wounded was superintendent of police of Assam’s Cachar district.

Himanta’s first hurdle

The incident was the first major test for Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma after he took over the reign of the state in May this year, fulfilling his long-time aspiration of grabbing the top job.

He had a long and reasonably successful stint as number two in the Tarun Gogoi-led Congress government from 2011-15 and later in Sarbananda Sonowal helmed the BJP government from 2016 until his recent elevation.

Until the firing incident, Sarma, who is also the convener of the BJP-led North East Democratic Alliance (NEDA), was on a sail pushing his party’s Hindutva agenda by restricting sale of beef, banning inter-state transportation of cattle and mulling adoption of two-child norms in Assam. His government’s Uttar Pradesh-style trigger-happy policing further raised his stock among the state’s saffron followers.

These apart, Sarma was also effectively playing the role of a political crisis manager for the BJP in the North East, endearing himself both to the party bosses at the Centre and his colleagues in the neighbouring states.

Honble @ZoramthangaCM ji , Kolasib ( Mizoram) SP is asking us to withdraw from our post until then their civilians won't listen nor stop violence. How can we run government in such circumstances? Hope you will intervene at earliest @AmitShah @PMOIndia pic.twitter.com/72CWWiJGf3

— Himanta Biswa Sarma (@himantabiswa) July 26, 2021

Only last month, he had a quiet meeting in Guwahati with Sudip Roy Barman, the leader of the dissident group in the Tripura BJP. Barman was reportedly hobnobbing with the Trinamool Congress to bring down Biplab Deb’s BJP government in the erstwhile princely state.

Sarma earned some appreciation from the non-saffron section of the populace as well for his government’s praise-worthy crackdown against drug mafia.

Then came Monday’s incident, which has laid bare chinks in his administrative as well as negotiating skills.

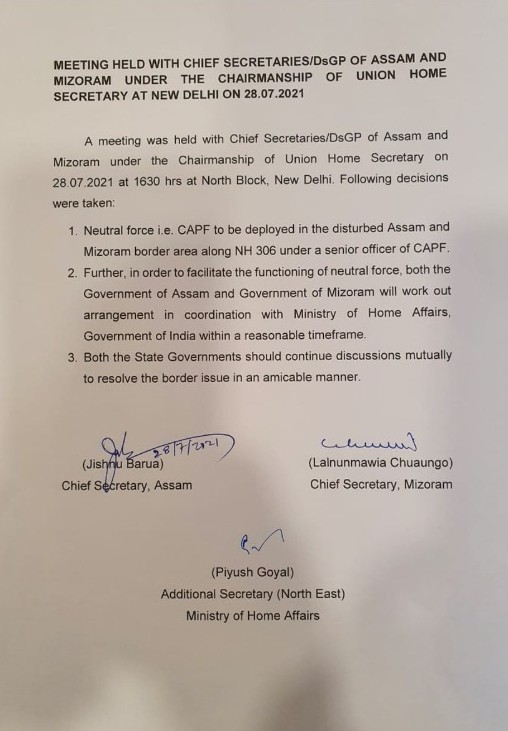

Soon after the firing incident, Sarma and his Mizoram counterpart Zoramthanga sparred on social media, resorting to blame games.

Shri @AmitShah ji….kindly look into the matter.

This needs to be stopped right now.#MizoramAssamBorderTension @PMOIndia @HMOIndia @himantabiswa @dccachar @cacharpolice pic.twitter.com/A33kWxXkhG

— Zoramthanga (@ZoramthangaCM) July 26, 2021

“The acrimonious spat in public between chief ministers of the two warring states was certainly not desirable when the tension was high on both sides of the state border,” said a former police officer of Assam, who did not wish to be quoted on the emotive issue.

Congress’s deputy leader in the Lok Sabha Gaurav Gogoi also criticised the twitter duel calling it “childish.”

Not stopping at pointing fingers at his counterpart, Sarma even shared some disturbing videos of the incident on social media, which had the potential to further provoke the situation.

“After killing 5 Assam police personnel and injuring many, this is how Mizoram police and goons are celebrating—Sad and horrific,” he tweeted on the night of the incident sharing a video that showed Mizoram Police personnel were being cheered by sticks-wielding civilians amidst back-patting, handshaking and high-fiving.

Minutes later he tweeted another video with the following comment: “Look at this video to know how personnel of Mizoram police acted and escalated the issue. Sad and horrific!”

Instead of playing a matured administrator, Sarma was clearly playing to the gallery in a knee-jerk reaction to deflect attention from the monumental failure of the two governments to de-escalate the tension which had been brewing in the disputed border area since October last year with sporadic incidents of violence and clashes.

The incident has given an opportunity to the opposition party to nail him on an issue which is very sentimental. Sarma knows more than anyone else that emotion is one card that the BJP cannot afford to lose.

The development further became embarrassing for the BJP as it came barely 48 hours after Union home minister Amit Shah went into a huddle with all the chief ministers of the north-eastern states in Meghalaya capital Shillong. One of the agenda of the meeting was resolution of border disputes among all the north eastern states by next year when the Independent India will turn 75.

“Instead of indulging in a childish Twitter duel with his NEDA counterpart, the Chief Minister of Assam should admit that the recent trip of Home Minister Amit Shah to Northeast India was a complete failure and merely a photo-op,” Gogoi had tweeted after the incident.

Instead of indulging in a childish Twitter duel with his NEDA counterpart, the Chief Minister of Assam should admit that the recent trip of Home Minister Amit Shah to Northeast India was a complete failure and merely a photo-op. https://t.co/nQ7mbElhW5

— Gaurav Gogoi (@GauravGogoiAsm) July 27, 2021

Incidentally, ruling parties of all the north-eastern states are NEDA constituents and they claim to have a great camaraderie among themselves.

Twist in the beef

Unfortunately, the border disputes and the Assam government’s overdrive to ban inter-state cattle transportation are threatening to disrupt the bonhomie, upsetting the BJP’s north-east expansion plan.

Christian-dominated north-eastern states are not very happy with the Assam government’s sensitivity over beef consumption. Meghalaya chief minister Conrad Sangma has openly raised concern over Assam’s move.

In a statement that has the potential to aggravate the relation further, Sarma even tried to link the border flare-up with his government’s decision to prevent inter-state cattle movement.

Claiming that some non-state actors were also involved in the firing incident, Sarma said “rumours” about Assam preventing beef supply to the rest of the region might have triggered resentment in a predominantly Christian state like Mizoram.

“It is a highly irresponsible remark not befitting a chief minister of a state. He knows well that border disputes have been festering for decades. The cattle transportation came only recently. So where is the link?” retorted Aizawl-based senior journalist Zodin Thanga.

Lingering colonial legacy

True, Monday’s incident was not the first such clash between two north-eastern states over a border dispute. On that very day, another major border skirmish, this time between Assam and Meghalaya was averted due to timely response by the Ri-Bhoi district administration of Meghalaya.

The tension mounted in Iongkhuli village on the border when a team of Assam government officials and senior police officials allegedly went there and prevented personnel of Meghalaya Energy Corporation Limited (MeECL) from erecting electric poles there.

The worst ever clash between the forces of the two states in the history of the region took place at Merapani in Assam’s Golaghat district in June 1985, when armed cops of Assam and Nagaland fought a fierce gun battle for about four hours, leaving 41 dead, including 28 Assam Police personnel.

Zoramthanga rightly pointed out that the present border dispute is a colonial legacy. When India attained freedom, the present states of Nagaland (barring Tuensang division which was part of the NEFA), Meghalaya and Mizoram were districts in Assam. While the state of Meghalaya was carved out of the districts of Khasi, Garo and Jaintia hills in Assam, Mizoram was Lushai Hills.

Arunachal Pradesh, comprising several frontier divisions, including Tuensang, was part of the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) administered by the governor of Assam.

Manipur and Tripura were independent princely kingdoms that merged with India only in 1949 to become ‘Part C States’, equivalent to present-day Union Territories.

At the time of reorganising Indian states and territories along linguistic lines by enacting the States Reorganisation Act, 1956, the Northeast remained untouched, undermining aspirations of ethnic communities, some of whom like the Nagas were waging armed rebellion for a sovereign independent state.

As the separatist movements started spreading from Naga hills to other parts of the region, the process of gradual administrative reorganisation of the region started with the formation of new states.

Nagaland was granted statehood in 1963 and Meghalaya in 1972. In the same year, Manipur and Tripura were elevated to full-fledged states. Mizoram too was carved out of Assam to become a Union Territory in 1972, and subsequently it became a full-fledged state in 1986.

Arunachal became a state in 1987, last among the seven sisters.

The idea behind the restructuring is to reduce conflicts by accommodating territorial aspirations of ethnic communities such as Nagas, Mizos, Khasis, Manipuris, Garos, Arunachalis and others.

The delineation of the state boundaries however failed to strictly conform to the ethnic specificity and also did not take into consideration the pre-independent era “historic boundaries” demarcated along ethnic lines, leading to the present-day festering inter-state border disputes in the region.

Assam, out of which most of the present north-eastern states have been created, insists on adhering to boundaries marked after Independence. But other states such as Nagaland, Mizoram and Meghalaya harp on “historic boundaries” as its territorial jurisdiction.

Adding communal colour

Despite these historic perspectives, attempts are often being made to give a communal angle to what is otherwise a purely territorial dispute.

Since most of the settlers on the Assam side of the disputed border areas are Bengali-speaking Muslims, a narrative is often being peddled that the contention over the boundaries was essentially a conflict between illegal-immigrants and indigenous tribals.

“The fight between the government and administration of Assam and Mizoram should not be projected as the fight between the indigenous Assamese and the Mizos. The Assamese need to understand a few things. No indigenous Assamese community resides in these border areas where the incident occurred,” wrote one Fra Seng Kham (Hemanta Madhab Gogoi) on his Facebook page.

His post was shared on his Twitter handle by a highly reputed journalist-turned-politician of Mizoram, David M Thangliana.

By adding a beef angle to the dispute, Sarma will only end up further complicating the already complicated dispute. This certainly cannot be the right neighbourly approach let aside resolution of the conflicts.