- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Across the barbed fences, Bengal and Bangladesh face similar challenges

The growth of communal forces besides posing threat to the growth story is also challenging the founding ethos of West Bengal and Bangladesh.

When Bangladesh was born in 1971, West Bengal was in the throes of a socio-political turmoil. Its best and brightest were leaving colleges and universities to wage a “class war”. Campuses were filled with the rallying cry of ‘Amar bari, tomar bari, Naxalbari, Naxalbari’ (Your home, my home is Naxalbari). Naxalbari, as it was even then, is a sleepy hamlet in Darjeeling district...

When Bangladesh was born in 1971, West Bengal was in the throes of a socio-political turmoil. Its best and brightest were leaving colleges and universities to wage a “class war”. Campuses were filled with the rallying cry of ‘Amar bari, tomar bari, Naxalbari, Naxalbari’ (Your home, my home is Naxalbari).

Naxalbari, as it was even then, is a sleepy hamlet in Darjeeling district in northern West Bengal. The otherwise nondescript village literally shook the entire country with a violent peasant uprising in 1967, making its place in history.

Soon the flame of revolt spiralled into a gigantic fire, leaving a trail of brutal killings and equally vicious police reprisal.

Among the noted victims of the violent lunacy carried out in the name of class battle were vice-chancellor of Jadavpur University Gopal Chandra Sen, whose throat was slit by a group of Naxalite students on the campus in 1970, and 76-year-old chairman of the All-India Forward Bloc and veteran freedom fighter Hemanta Kumar Basu.

Even a 15-year-old schoolboy, who had been trying to break his Naxalite ties, could not escape the mindless fury. He was dragged out of the classroom and stabbed.

The police responded with equal brutality, carrying out a series of extrajudicial killings, including the infamous Barasat massacre wherein 11 youths were killed in a Kolkata suburb on the night of November 19, 1970, after they were rounded up from a secret meeting in Kolkata’s Maidan area.

A top Naxal leader and ideologue Saroj Dutta, who had served as editor-in-chief of the Amrita Bazar Patrika during the 1940s, was killed in a fake encounter in Maidan early morning on August 5, 1971, after being picked up from the house of one of his friends the previous night.

Even the leader of the Naxalite movement Charu Majumdar died in a mysterious circumstance in police custody on July 28, 1972.

Even cadres of mainstream political parties took part in anti-Naxal reprisal. “Almost all political parties here have enlisted private armies of goondas (gangsters),” the New York Times had mentioned on November 26, 1970 while reporting on the tactics being used to halt the Naxalite terror.

The Naxalite turmoil thus left behind the praxis of political violence, which is still prevailing in the state. It was also the time when Bengal witnessed the rise of self-defeating militant trade unionism that led to the state’s economic downfall.

The share of West Bengal in the country’s total industrial output halved to 10.9% in 1975-76 from 22.2% in 1959, according to Central Statistical Organisation’s (CSO) old data.

Cruel birth of Bangladesh

The year 1971 in particular was very gory for Bangladesh too. After the liberation war broke out in what was then East Pakistan in March that year, the Pakistani army launched a massive crackdown codenamed ‘Operation Searchlight’.

Their prime targets were political activists, intellectuals, students and Hindu minorities who had then comprised about 20% of the province’s population. On March 25, the army stormed Dhaka University, lining up and executing students and professors.

“A total of 300 students’ deaths was estimated,” wrote Archer Blood, the then counsel general of US at Dhaka in his book The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh.

Independent researchers say between 300,000 and 500,000 people died during the mass uprising for freedom. The Bangladesh government puts the figure at three million.

The Bangladesh War of Independence lasted only nine months but it took a heavy toll on its human as well as economic resources.

“When the war ended, the economy was left prostrate. Businesses were destroyed or in despair, sweeping away fortunes pushing many well-to-do into penury,” says Biswajit Das, London-based special affairs editor of bdnews24.com, Bangladesh’s most reputed online news portal.

American politician and diplomat Henry Alfred Kissinger famously dubbed it a “basket case” at its birth in 1971.

Moving on and ahead

Both West Bengal and Bangladesh have moved ahead thereon, outliving the scar of violence. Or did they?

The story of Bangladesh is particularly worth telling. It has become one of the most startling success stories in Asia. So unexpected and outstanding was its growth story that when its GDP growth rate surpassed Pakistan’s in 2006, many pundits had dubbed it fluke.

Similar cynicism was expressed when the recent International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) World Economic Outlook report showed the per capita income of an average Bangladeshi citizen would be more than the per capita income of an average Indian in 2020.

What naysayers tend to ignore is that the IMF report also showed that from 2017 onwards when India’s GDP growth rate has been constantly declining, Bangladesh’s has been steadily growing. India’s GDP growth rate for 2017 was 7.04% whereas Bangladesh’s was 7.6%. In India, the growth shrunk to 6.12% in 2018 while Bangladesh registered a growth rate of 7.9%. In 2019, India’s GDP further slipped to 5.02% while Bangladesh’s increased to 8.2%. The IMF report said in 2020-21 India’s GDP will contract by 10.3% while Bangladesh’s GDP will increase by 3.8%.

Even in the Global Hunger Index 2020, Bangladesh outperformed India, ranking 75 whereas India occupied the 94th position among 107 countries.

In various other social indicators like life expectancy (Bangladesh’s 72.72 years as against 69.73 years in India), Bangladesh is ahead of its much bigger western neighbour.

“We are not in competition with India. India is a much bigger country with a vast and diverse economy. Bangladesh in comparison is a much smaller economy and its GDP growth is largely driven by exports of readymade garments and remittances,” says Afsan Chowdhury, a Dhaka-based political commentator and Bangla Academy Award winning research scholar.

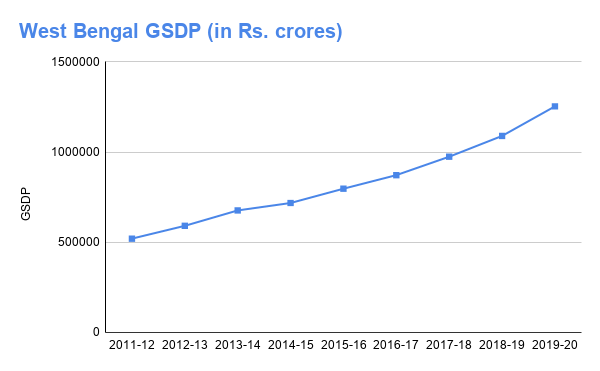

Contrary to popular perception, in the past few years West Bengal too witnessed revival of its economy. In fact, in 2018-19, at constant 2011-12 prices, West Bengal’s GSDP growth rate of 12.58% was the highest in the country.

The state’s economy is mainly propelled by agriculture, MSMEs and the service sector. It’s the largest producer of paddy and vegetables in India and second largest tea and potato producer.

It has the second highest number of MSMEs in the country, accounting for 14% of India’s total. The services sector contributes 59% of West Bengal’s GDP.

Overall West Bengal is the sixth largest economy in the country. True, it is way behind other bigger states such as Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu. But in comparison to the last decade, it performed better in the current decade in most socio-economic parameters raising hope of its economic recovery.

For instance, per capita net state domestic product (current prices) in the last one decade has more than doubled from ₹47,245 in 2010-11 to ₹1,15,748 in 2019-20, according to the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) latest data.

In the social sector, the state topped in reducing school dropout rate which came down from 3.3% to 1.5% even as it went up from 4% to 5.5% at the national level, according to the Annual State of Education Report (ASER) 2020.

In rural employment generation too, the state performed better than the national average, as per RBI data. In rural Bengal 35 in 1000 persons are unemployed whereas overall in India it is 50 in 1000 persons. Bengal’s performance is better than many industrially developed states like Tamil Nadu (64 in 1000 persons) and Maharashtra (42 in 1000 persons). It’s just marginally behind Gujarat (33 in 1000 persons).

Infant mortality rate in the state came down from 33 per 1000 in 2010 to 22 in 2018, as per the RBI’s statistical handbook released in October this year. The national average is 32 per 1000.

Sustaining the momentum

The question now is whether Bangladesh and West Bengal can sustain the upturn. For sustainability, it is essential that policy makers in both Bengals uphold secular values and check growth of religious fanaticism.

Unfortunately, both West Bengal and Bangladesh are losing their secular plot and for that, current ruling dispensations in both Dhaka and Kolkata cannot escape their share of blame.

Currently, Bangladesh is witnessing massive agitation by hardline Islamist group against the installation of a statue of the country’s founding father Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The group, Hifazat-e-Islam, mainly comprising madrasa teachers and students, wants Bangladesh to follow Shariat laws.

Junaid Babunagari, the new chief of radical Islamist group Hifazat-e Islam, has threatened to pull down “all statues, no matter which party erects them” in Bangladesh, as statues are against Sharia.

Among his other demands are to stop ISKCON’s activities in Bangladesh, to officially declare the Ahmadiyas as ‘non-Muslim’, to close the Embassy of France and expel the French ambassador.

“We are confronted with a Taliban leader in our midst. The choice before Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina is either to stop him or let the Republic become another Pakistan,” says Shahriar Kabir, leader of the Ekattorer Ghatak Dalal Nirmul Committee and the country’s strongest secular voice.

Bangladesh in the past few months also witnessed more than one incident of communal violence targeting Hindu minorities. Islamist threats last month forced the country’s biggest sporting icon cricketer Shakib Al Hasan to make a public apology for attending a Hindu ceremony in India.

“The rise of radical elements in Bangladesh is definitely a concern as it will reverse our economic growth. We cannot afford to make the same mistake that Pakistan has made,” Awami League MP and former Bangladesh minister Biren Sikder told The Federal.

In West Bengal, the central government’s data shows that the incidents of communal violence incidents have sharply increased over the past five years. This is the period when the influence of Hindu right-wing outfits, including the BJP, has witnessed an upsurge.

According to a government of India report, last year between January 1 and October 30, West Bengal witnessed 79 incidents of communal incidents as against 57 reported in the year before.

Just as Shakib Al Hasan was targeted for attending a Hindu religious event, the right-wing social media trolls continuously target West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee for a poster of her offering Namaz wearing a hijab. She is even called ‘Mamata Begum’ for her minority outreach and often being accused of Muslim appeasement.

The rise of radical Hinduism in West Bengal, negates the post-partition founding principle of the state based on political consensus on communal harmony, observes Kolkata-based political commentator Nirmalya Banerjee.

Inadvertently, the ruling dispensations in Bangladesh and West Bengal helped the rise of right-wing forces. In both the Bengali heartlands, the respective ruling parties, the Awami League and the Trinamool Congress tried to annihilate opposition space, becoming ruthlessly intolerant against any dissent.

A professor Ambikesh Mahapatra was arrested for circulating cartoons lampooning CM Mamata Banerjee in 2012, just about a year after her TMC came to power with a slogan ‘Badla noi badal chai’ (we want change, not revenge).

The same year a case was slapped on Shiladitya Chowdhury, a marginal farmer, branding him a Maoist for questioning Banerjee on rising fertiliser prices.

Attacks on workers of opposition parties are rampant.

The tipping point was the 2018 panchayat elections wherein about 34 per cent of the seats went uncontested as opposition could not field candidates there due to intimidation of the TMC. At least 13 people were killed and more than 50 were injured in political violence on the polling day alone.

This use of force to crush opposition led to massive polarisation at the grassroots-level against the TMC, with even the Left supporters turning saffron.

Similarly, in Bangladesh, Awami League’s attempt to crush its main rival, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) saw radical Hefazat-e-Islam feeling the vacuum.

(BNP chief Begum Khaleda Zia is now lodged in jail on corruption charges. Her son Tarique Rahman is in forced exile in London.)

The growth of communal forces besides posing threat to the growth story is also challenging the founding ethos of the two political entities ruled by two woman leaders on either side of the barbed fence that separates what was once the undivided Bengal.