From a sleepy town to thriving city, the gripping story of Karur's transformation

Karur may not be as popular as Coimbatore, Madurai or even Salem, but this centrally located district in Tamil Nadu is significant and unique in its own way.

One of the oldest towns in Tamil Nadu, the history of Karur dates back to the Sangam period. The Tamil epic ‘Silapathikaram’ says that it was from here, Cheran Chenguttuvan, a Chera king, ruled the Tamil land for many years.

The Chera king was followed by the Pandyas, Pallavas, later day Cholas, Naickers and Tipu Sultan. This district shot into limelight after the infamous sand mining controversy near the Amaravathi river, a Cauvery tributary, in 2006.

To drive home how the district came under the grip of sand mining, in 2008, the late Professor S Neelakantan, an economist from Karur, published a book titled ‘Oru Nagaramum Oru Gramamum’ (A City and A Village), in which he quotes his 1996 Working Paper, where he had observed:

To drive home how the district came under the grip of sand mining, in 2008, the late Professor S Neelakantan, an economist from Karur, published a book titled ‘Oru Nagaramum Oru Gramamum’ (A City and A Village), in which he quotes his 1996 Working Paper, where he had observed:

“The Amaravathi sand became a “valuable” economic commodity with increasing construction activities in Karur and Coimbatore. Large-scale sand mining started in the 80s. Sand was exported to all towns from Karur to Coimbatore in the late 80s. Since it affected the percolation of water to their pipelines, the neighbouring hamlets joined together to prevent its mining in Chettipalayam-Appipalayam- Karuppambalayam belt in the late 1980s.”

Further, he wrote, “Now political pressure is at work to break this co-operative move. How long this unity would remain in the face of high monetary inducements collectively to the hamlets and individually to influential persons in the hamlets is a matter of surmise. Already a group has started arguing that the co-operative ban, cannot be ‘enforced’ because any big flood would wash away the top sand in river to the lower riparian hamlets, which have already lost it by excessive sand mining. So, they prefer the hamlets to reap the monetary benefits now rather than to lose both the sand and money rewards simultaneously in the next floods. There is an element of truth in their argument”.

Also read: Temple land recovery: TN makes inroads despite documentation challenges, tenant resistance

KR Athiyaman, an entrepreneur-turned-journalist, who hails from Karur, observed, “Fifteen years later, Neelakantan’s fears have come true. Due to rampant sand mining, his native village Chettipalayam has become a ghost village, since most of the villagers have migrated to Karur town in search of livelihood. Agricultural activities too have literally come to a standstill there.”

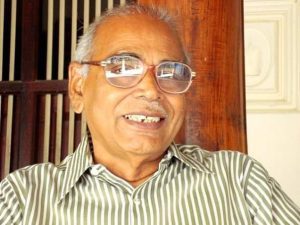

Neelakantan did witness the transformation and the death of his village. At the age of 88, he passed away on March 19 in his village, due to an age-related illness.

A Tamil economist

Born on 19 December 1935 in Chettipalayam, a village in Karur, Neelakantan worked as an economics professor at University of Madras and Bharathidasan University. As a Fullbright scholar from 1986-1987, he went to Washington University, where he learnt new institutional economics from Douglass C North, who later went on to win the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1993.

In 1990, he joined the Madras Institute of Development Studies as its director and served there till 1995. Post his retirement, he started publishing books on economics in Tamil and introduced the ideas of various economists across the globe, starting from Adam Smith to Karl Marx, by writing in an easy-to-understand style that attracted many readers.

In his book, he compares his native hamlet Chettipalayam with Karur town, and analyses the developments unfolding in both places in the last 100 years.

The rise of Kongu Vellalars

Neelakantan’s book helps us to understand how the Karur region grew from its glorious historic past until 2006. It gives us a glimpse of how the rural and urban parts of a district in Tamil Nadu gradually developed over the years.

The Kongu region has always been grateful to the Kongu Vellalars or Gounders, a dominant community, for their significant role in its growth. So, one would assume the same happened in Karur. But, Neelakantan provides a different history.

The district started to develop between 1930 and 1940, when it gradually embraced textile industries. At the same time, Coimbatore had more than 40 textile mills, out of which only four were founded by Gounders. In Karur, it was the Mudaliar community that first established textile mills. And, the bus body manufacturing industry was started by the Naidu community.

“Until the 1950s, the Kongu Vellalars missed the bus. But once they hopped on to it, there was no turning back,” the author said in the book.

Also read: Perumal Murugan’s Pyre, the Booker longlist, and global caste dialogues

Progress across sectors

The textile industry in Karur became a household name for its carpets across the globe only in the 1950s. Until then, the finished product from the mills would be taken across the country and stored in the godowns of their distributors. They would replace the stocks once it was cleared but this process took a long time.

In the 1950s, Amarjothi, an entity, started a novel initiative. Instead of storing its stocks in godowns, the firm started to showcase its samples to the textile fraternity in other states through their representatives. And, it would only send the exact product and the quantity demanded by its customers after receiving a firm order. In this way, the companies were able to save a lot of their money and energy. Later, the method was picked by other companies.

This resulted in a chain of reactions such as mushrooming of dyeing industries, the entry of private finance companies that lent loans only based on trust in the 1960s, private bus companies and the business of renting marriage halls in the 1980s, the arrival of real estate boom in the 2000s, which were all instrumental in the region’s growth.

By 1927, Chettipalayam had a progressive side as girl students were admitted to an elementary school. “Not only that. The then Karur Taluk Board president Pasupathipalayam Kaliyanna Gounder, also built a well, where the girls could learn swimming from early morning to afternoon,” wrote Neelakantan.

Not a rosy picture

In his book, Neelakantan, however, does not just paint the rosy side of the growth story of Karur. In the 1940s, consuming toddy was shameful and he reminisces about an incident when two hardcore alcoholics Rathina Sabapathy Gounder and Nadana Sabapathy Gounder, became Gandhians on the advice of the then Congress leader C Rajagopalachari. They were the sons of a zamindar.

The ‘tex’ and real estate industry’s growth has also come at a cost. They have caused the river Amaravathi, a tributary of the Cauvery river, to become polluted. Unchecked sand mining is another problem that the district constantly tussles with.

Similar to the 2015 Chennai floods, the Chettipalayam village also suffered from floods caused by Kodaganar river, a tributary of the Amaravathi river, in 1977. Seventeen inches of rain were recorded on a single day. The floods happened due to the lack of proper maintenance work in the Kodaganar dam.

Until the 1970s, agriculture was practised during the day. After free power was given to farmers in the 1990s, the farmers were pushed to carry out most of the agri works at night, including watering their lands.

“It was because the government provided only six hours of free power in the daytime for three-phase motor pumps. Whereas in the nighttime, the two-phase power can be used between 10 pm and 6 am. So most of the farmers, despite knowing it is illegal to use two-phase power to run three-phase motor pumps, continued to do so. This resulted in a lot of farmers dying of snake bites in the nighttime,” pointed out Neelakantan.

The author ends the book on a positive note stating that villages like Chettipalayam, despite all the odds, made progress with the help of systems that are in place like Panchayat Raj.

Also read: The arid, defiant world of International Booker-longlisted Tamil writer Perumal Murugan

Karur between 2008 and 2023

In journalist Athiyaman’s view, even as the economic growth picked up pace in Karur town, the village side started to perish in the last 15 years.

“In his book, Neelakantan makes a passing remark on mosquito net manufacturing in Karur. Fifteen years later, the district started exporting nets across the globe. Similarly, the district has also witnessed thousands of people who were once labourers who have become entrepreneurs. Most of them were basically farmers who were pushed to poverty due to the polluted water caused by the dyeing industries, groundwater depletion and rampant sand mining,” he said.

The landlords of Chettipalayam, who had hundreds of acres of land, sold them over the years for different reasons. Their descendants, too, looked to the urban areas to build their lives.

Karur’s political relevance today

For many years, Karur was not remotely connected to any major political turn of events in the state.

However, today the situation is different due to the presence of two prominent politicians, V Senthil Balaji, the minister for electricity, prohibition and excise and K Annamalai. The district has now come under the radar of journalists.

Senthil Balaji was with the AIADMK earlier and had served as a minister for transport between 2011 and 2015. The latter is a former IPS officer, who worked in Karnataka and now heads the state BJP unit.

Both leaders contested in the 2021 Assembly elections from Karur district. While Senthil Balaji contested from Karur constituency and defeated AIADMK’s MR Vijayabhaskar, Annamalai fought from Aravakurichi and lost to DMK’s R Elango.

It seems Senthil Balaji has joined the DMK at a crucial time, when the party literally has no charismatic leader from the Kongu belt, an AIADMK stronghold. Balaji’s capacity to organise mega party conferences in Karur and other parts of the Kongu region has not gone unnoticed by party leaders.

On the other hand, Annamalai, who went against the advice of his party men to contest from Aravakurichi, dug his own grave. He lost largely due to his support for the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in Pallapatti village in the constituency, where a significant number of Muslims live.

Both politicians belong to the Kongu Vellalar (Gounder) community. The DMK is in need of a leader from the community in the Kongu belt, and is grooming Balaji with an eye on this particular vote bank.

Neelakantan’s book provides an insider’s perspective on how Karur slowly morphed over the years into this thriving district. Though the book is narrated from the view of a Kongu Vellalar, the author’s solid research on entrepreneurship, caste customs, women’s education, agriculture, exploitation of river sand, etc., gives us a sense of how the district managed to push itself forward, despite all odds.