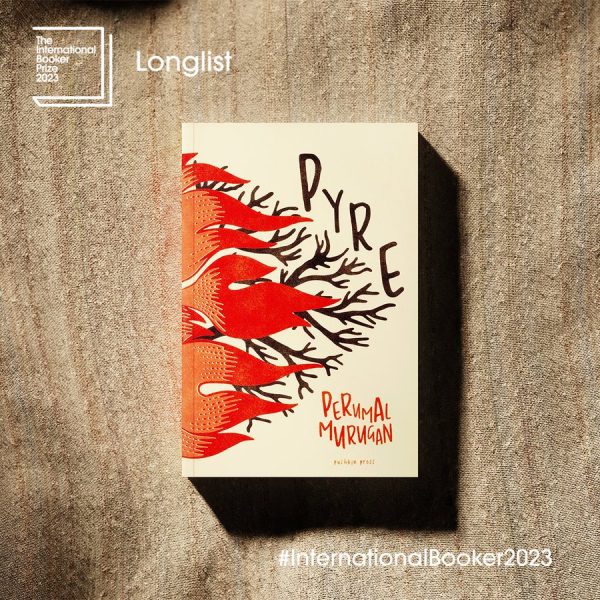

Perumal Murugan's Pyre, the Booker longlist, and global caste dialogues

How far is the Booker selection a reflection of Western curiosity on the caste system?

“What is a village but a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow mindedness, caste and communalism,” remarked Dr BR Ambedkar, the great social reformer, about life in Indian villages.

Well-known Tamil writer Perumal Murugan’s Pyre, the English translation of his 2013 Pookkuzhi, which figures in the 2023 International Booker Prize longlist, seems to aptly reflect Ambedkar’s view on villages being trapped in a ‘den of ignorance’.

Also read: The arid, defiant world of International Booker-longlisted Tamil writer Perumal Murugan

In Pyre, Murugan drives home the prevailing ‘narrow-minded’ culture in a village with these succinct lines: “At first glance, this village looked like it was made of a few houses surrounded by a large expanse of land, and that anything could easily enter and get around. But that was an illusion. In truth, not even the wind from elsewhere could enter this space. The air in these parts had circulated within the confines of this place and had turned poisonous. The space would not allow anything to enter.”

Caste dialogues across globe

It does seem to the literary community in Tamil Nadu that Murugan’s book, based on caste hatred and violence, has made it to the Booker longlist at the right time.

For many years now, Dalits in western countries like the US have been complaining that NRIs are casteist and practise caste discrimination with fellow Indians abroad. Major rows have periodically broken out over this issue, especially in the US. For example, there was a big ruckus when Google cancelled a talk on caste bias last year by Thenmozhi Soundararajan, a Dalit activist and executive director of Equality Labs. In 2020, a group of 30 Dalit women had published a letter in the The Washington Post, over rampant caste discrimination in Silicon Valley.

This February, Seattle became the first city in the United States to ban discrimination based on caste. In March, the Toronto District School Board became the first school in Canada to recognise the caste discrimination existing in the city’s schools.

Also read: How a Sri Lankan Tamil novel ‘foretold’ Vengaivasal caste atrocity

It seems the western world too has been compelled to listen to the marginal voices because of the seminal works of Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste (2020), and a Harvard academic Suraj Yengde’s Caste Matters (2019).

Copious work on caste discrimination

According to Azhagiya Periyavan, a Tamil writer known for his incisive writing on caste issues, problems like caste and racial discrimination in Asian and African communities, respectively, have produced a copious amount of literary work all these years. “The western society finds the caste problem particularly interesting because it seems different and unusual,” he said.

“I think the Western society tries to understand the Indian caste system from the racial apartheid experience faced by Africans. They think caste discrimination is something like racial bias. But, the problem is much deeper and rather different,” he added.

Explained: How Indians took caste to the US that was already in the grip of ‘casteist’ bias

“Today, westerners see talented Afro-Americans as an asset but this cannot happen in a society where there is a caste hierarchy. The recent incidents over caste bias possibly kindled interest among the westerners to know about caste in a much broader sense,” he pointed out, adding that Perumal Murugan’s book on caste, love and inter-caste marriage would give them greater understanding on how caste works in its everydayness.

Selective representation

However, Periyavan said the caste issue was not being presented to the world in its entirety. Most of the translations from Tamil to English are done by translators from upper castes, who only pick up literary pieces that ‘suit’ them, he said.

“The publishers are also a part of this neglect. They should have taken the works of other popular Tamil writers on caste, such as Imayam and Bama, much earlier to English and other languages,” he argued. “But it is happening at least now and we are hoping Pyre will fetch this award.”

Caste and love are the two recurring themes which figure in most of Perumal Murugan’s works. His 2010 novel Madhorubagan (translated in English as One Part Woman), which landed in a huge controversy triggered by right-wing groups and even led to the writer announcing his ‘literary suicide’ in 2015, went on to win a Sahitya Akademi award for its translator Aniruddhan Vasudevan in 2016. In 2018, the book also made it to the US National Book Award longlist.

Also read: For poverty-struck, caste-oppressed individual, does religion matter?

A year after, Murugan published a new novel titled Poonachi (The Story of a Black Goat) in 2017. Translated by N Kalyanaraman, the English edition figured in the US National Book Award longlist in 2020. It also won Sahitya Akademi for translation in 2022. Despite receiving rave reviews in the media including in The New York Times, Poonachi did not make it to the shortlist. Now, for the third time, Murugan’s work has got an opportunity to win him international recognition.

A counter view

A well-known Chennai-based translator, who preferred to remain anonymous, had a counter view. The dialogues on caste discrimination are certainly happening in Western countries, but it is still not a pressing issue for them, he said.

“They view a Tamil book just like any other creative fiction from a lesser known society. Compared to the number of translations happening in western countries, where English, French, Chinese and Japanese translations dominate, translations from South Asian languages are a marginal number. In this backdrop, even if Murugan’s book gets shortlisted it is enough reason for us to celebrate,” he said.

Further, the translator said, Pyre got into the Booker longlist probably because of Parul Sehgal, an American literary critic who had reviewed the English translation of Poonachi for The New York Times’ She is currently a member of the International Booker Prize longlist jury.

Simple, yet straightforward

The story of Pyre is a simple one. It revolves around the love affair of Kumaresan and Saroja. Working in a soda factory in Tholur city, Kumaresan, a native of Kattuppatti, an arid village, falls in love with city-bred Saroja. After marrying, they return to Kumaresan’s hometown, where they are ostracised by the villagers.

Facing the heat from villagers and her relatives, Marayi, Kumaresan’s mother, is driven to try and kill Saroja. Whether the young woman becomes a victim of hate-killing forms the rest of the story.

Though the author claims in his preface that the story is fictional, Pyre reminds the readers of many hate-killings that have happened in Tamil Nadu in the recent past. It is interesting to note that the Tamil edition of the book, published in 2013, has been dedicated to R Ilavarasan, a Dalit youth whose body was discovered on the railway tracks in Dharmapuri district, after he eloped with Divya, a Vanniyar girl, and married her.

“This is a novel about caste and the resilient force that it is, but it is also about how strangely vulnerable caste and its guardians seem to feel in the face of love, and how it often seems to assert itself both in everyday acts of discrimination as well as in moments of most unimaginable violence,” said the translator quoted above. An observation that hits home when it comes to the horrific issue of honour killings.