Simranjit Singh's Sangrur victory jolts AAP's Mann in Punjab

The AAP may take solace in the fact that it did not lose out to a renascent Congress or Akali but the defeat should teach Bhagwant Mann - and Arvind Kejriwal - some urgent lessons about the difference between Delhi and Punjab.

Just over three months after it registered a historic victory in the Punjab assembly polls, the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) suffered a huge electoral blow, on Sunday (June 26), losing the by-poll for Sangrur Lok Sabha seat to hardline Sikh leader, Simranjit Singh Mann.

I am grateful to our voters of Sangrur for having elected me as your representative in parliament. I will work hard to ameliorate the sufferings of our farmers, farm-labour, traders and everyone in my constituency.

— Simranjit Singh Mann (@SimranjitSADA) June 26, 2022

The constituency had elected Bhagwant Mann to the Lok Sabha for two consecutive terms since 2014. The by-election was necessitated as Bhagwant vacated the seat in March after taking over as Punjab’s Chief Minister.

The defeat in Sangrur comes as a rude reminder to the AAP of the transient nature of electoral buoyancy, the pitfalls of ignoring socio-cultural fault lines and the misplaced belief that theatrics that work in its favour in Delhi will reap votes in Punjab too. The loss, though by a slender margin of 5,822 votes, should jolt both AAP and its Chief Minister, as the party had won all 10 assembly segments of Sangrur in March this year with Bhagwant too registering his debut assembly win from the district’s Dhuri seat.

Close contest

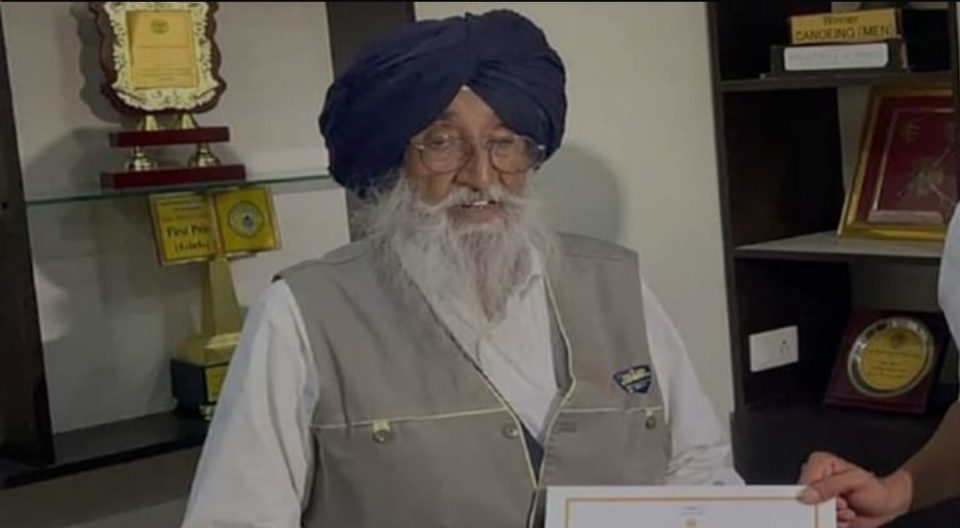

It had been clear for some time that the contest in Sangrur was a close one between AAP’s Gurmail Singh and Simranjit Singh Mann, the 77-year-old former two-term Lok Sabha MP from Sangrur and chief of the Shiromani Akali Dal (Amritsar). The AAP’s massive wins across all assembly segments of Sangrur just three months back and the fact that the seat had been won by Bhagwant Mann in the past two Lok Sabha polls had led many to believe that the party will retain the seat, albeit with a narrow margin. The results have proven otherwise.

In many ways, the AAP’s defeat is a result of its shoddy performance during the brief period that it has ruled Punjab and the fast gaining impression that Bhagwant has surrendered the interests of the state before a ‘Delhi party’ and its boss, Arvind Kejriwal.

The circumstances under which the Sangrur bypoll was contested need to be elaborated.

Fault lines in Punjab

Ever since AAP romped to power with an unprecedented 92 seat majority in the 117-member Punjab assembly this March, Kejriwal and Bhagwant have, arguably, used the win to amplify the party’s electoral prospects in poll-bound Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh while paying little heed to the growing law and order concerns, administrative lapses and voter disaffection within the state.

In the past three months under AAP’s watch, Punjab has witnessed a clueless administration and police force failing to prevent a series of daylight murders by trigger-happy gangs, including the highly publicised killing of Punjabi singer and budding Congress politician, Sidhu Moosewala that triggered an outpouring of anger against the state government.

Moosewala was gunned down a day after the Punjab government halved his security detail and went to town patting its back for reducing or withdrawing the security provided to VIPs – politicians, bureaucrats, religious leaders, etc. The state’s security apparatus had also failed to prevent communal clashes that rocked Patiala on April 29 or the grenade attack at the Punjab Police’s Intelligence headquarters in Mohali on May 9.

Also read: Big setback for AAP in Punjab as party loses Sangrur seat held by Bhagwant Mann earlier

These glaring lapses showed the AAP government’s incompetence in maintaining law and order in a state that still has painful memories from a not-so-distant violent past. Instead of addressing these as a priority, the CM was occupied either in announcing populist measures – anti-corruption helpline, free electricity, et al – or campaigning for his party alongside Kejriwal in Gujarat and Himachal, or worse, ordering the Punjab police to hound Kejriwal’s critics such as Kumar Vishwas, Alka Lamba and Tajinder Bagga.

As a result, the AAP, which came to power promising badlaav (change) in Punjab, increasingly began to look like the legacy parties, Congress and the Shiromani Akali Dal, that had previously ruled the state since its reorganisation in 1966, but with one major difference – it came across as manifestly incompetent in running a state that has complex internal security issues and even more complicated socio-cultural and religious landscape.

In a state where the regional identity of a Punjabi or the religious identity of a Sikh coupled with the historical symbolism of Punjab never bowing to Delhi are a matter of personal pride to a vast majority, the perception over Bhagwant Mann acting solely to please his Delhi counterpart has, arguably, hurt AAP more than any incident that showcased its government’s administrative lapses and incompetence.

The CM’s palpable subservience to his party boss each time Kejriwal takes centre stage at an event within Punjab or in Gujarat or Himachal and leaves Bhagwant Mann hanging from the window of his vehicle or nodding in quiet acquiescence have added to the growing litany of bad optics for the party.

It may be no exaggeration to say that AAP’s brief but bumbling performance in government and the conduct of Bhagwant Mann as CM collectively created the circumstances for Simranjit Singh Mann’s candidature from Sangrur – and eventually prepared the ground of his surprise victory. The AAP’s failure to fathom the fault lines of Punjab – political, historical, religious and cultural – created a situation where the axis of Sikh and Punjabi identity took prominence over promises of change.

Simranjit Singh’s win significant

Simranjit, described variously by commentators as a hardline Sikh leader with pro-Khalistan leanings and someone who had the backing of Punjab’s influential Panthic (Sikh clergy) leadership, came as a contrast to all the accusations and taunts that AAP and Bhagwant attracted since assuming power.

If Bhagwant was portrayed by critics as Delhi’s rubber stamp, Simranjit was seen as a veteran warhorse defending the cause of Punjab and Punjabiyat. AAP desperately sought to shed the taint of its past dalliance with Khalistani leaders by showcasing its concerns for Hindus but, in turn, came across as a party that had no understanding of Punjab’s historic syncretism.

Also read: AAP’s Durgesh Pathak defeats BJP rival in Rajinder Nagar assembly bypoll

Simranjit, on the other hand, made no apologies for his radical views that chequered his political past but asserted his conviction for preserving Punjabi ethos and identity. Though 77 years old, Simranjit reached out to Sangrur’s youth – speaking about their problems, aspirations and challenges while also tapping into the growing unrest within this electoral bloc that has had little going for itself in recent years and has been hemmed in by growing unemployment, drug addiction and crime.

In Simranjit’s victory, Sangrur and Punjab may have found a strong, even if controversial, voice in the Lok Sabha. However, his win against AAP’s Gurmail Singh and candidates fielded by other legacy parties – Shiromani Akali Dal’s Bibi Kamaldeep Rajoana (sister of Balwant Singh Rajoana, assassin of former CM Beant Singh), Congress’s Dalvir Singh Goldy and the BJP’s Kewal Singh Dhillon – may also be an ominous sign of pro-Khalistan and Sikh extremist sentiments on the upswing.

That the Congress and the SAD finished a distant third and fifth respectively show that Punjab’s key Opposition parties are far from scripting their revival. The failure of the Congress to bounce back even after its young leader Sidhu Moosewala’s murder triggered widespread uproar against the AAP government shows that the time ahead for the Grand Old Party doesn’t look too promising.

The AAP may take solace in the fact that it did not lose out to a renascent Congress or Akali but the defeat should teach Bhagwant Mann – and Arvind Kejriwal – some urgent lessons about the difference between Delhi and Punjab.