What Air India’s deal to buy 470 aircraft tells free-market fundamentalists

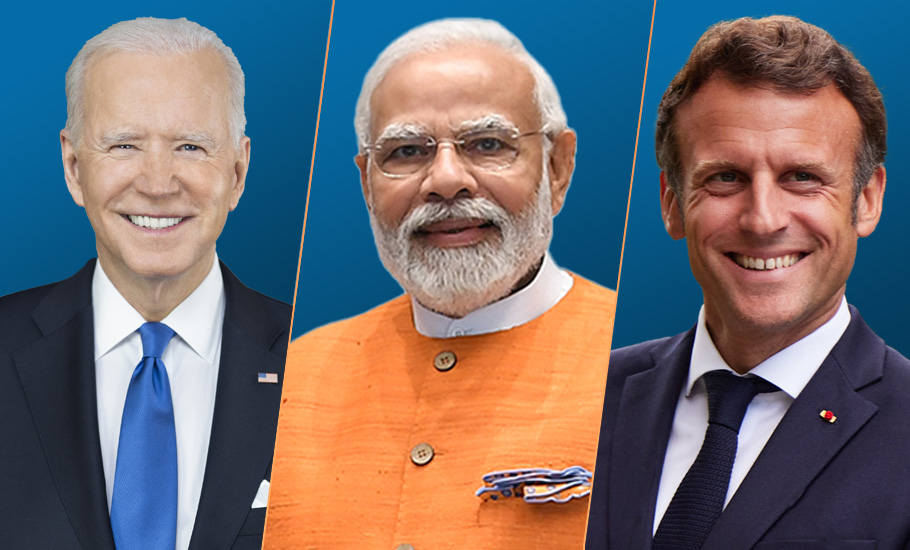

Three heads of government made excited announcements in the wake of the deal’s announcement, demolishing the claim of Chinese walls between the state and business

Aeroplanes make noise when they fly, they transport people and goods fast across vast distances, they make money or lose the stuff, when part of an airline. They are marvels of technology and, at present, account for about 2 per cent of global emissions of climate-change-inducing greenhouse gases.

They are, and perform, very many things. Providing ideological clarity is not one of the functions one counts among these flying machines’ versatile roles. But with the announcement of Air India’s fleet expansion plans, in which the airline proposes to acquire 470 aircraft, 250 from Airbus and 220 from Boeing, the proposed deal has become a lens through which to view the nature of the relationship between the state and business.

Opinion: Budget will boost growth, provided budgeted capex materialises

The government has no business to be in business. The Indian information technology industry grew to be what it is only because the government was absent in the sector. Market forces should decide where capital should go and how companies are run, governments should just focus on infrastructure, law and order and macroeconomic stability.

Soft-pedalling economic reform

The absence of big bang privatisation announcements in the Budget means the government is soft-pedalling economic reform. We hear such assertions and their variants on a regular basis from assorted pundits and political commentators on TV and in print. These pundits also gleefully scorn Nehru for his alleged socialist proclivities and praise the Modi government for its supposed pro-market stance of economic policy, never mind the production-linked subsidy schemes, selective protectionism and liberal servings of a Pradhan -Mantri-seasoned alphabet soup of ever-proliferating schemes, each ladleful meant to nourish citizen life in some aspect that had been deprive of state support hitherto.

Also read: Air India-Boeing deal to create 1 million jobs in US: Biden tells Modi

The deal is to buy 220 planes from Boeing and 250 planes from Airbus, engines from British Rolls Royce, American GE and Franco-American CFM International, a 50-50 partnership between GE and France’s Safran Aircraft Engines. Air India is also acquiring an option to buy 70 more aircraft from Boeing, which would raise the value of the Boeing deal from $34 billion to $45.9 billion. The planes being bought from Airbus would cost a total of $39 billion.

Air India is a commercial airline, albeit newly privatised. Boeing, Airbus, GE, Rolls Royce and CFM International are all commercial operations. Yet this commercial deal among commercial entities has excited three heads of states, of the US, France and India, to make joyous announcements, video presentations and long-distance phone calls attesting to mutual cooperation. Business, after all, does seem to be the business of governments, especially when it is big enough.

The Boeing deal, said US President Joe Biden, would create a million jobs across 44 American states. All the jobs would not call for four-year degrees, he added. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Biden cooed to each other on the phone, in the afterglow of the Air India announcement. The deal would create jobs in India, too, as Boeing procures assorted parts from Indian companies, as well. French President Emmanuel Macron also waxed eloquent on Indo-French cooperation, following the deal’s announcement.

People want well-paying jobs. When jobs become scarce, they blame ruling politicians. It is only natural that politicians want to take credit when large business deals occur that create a good many jobs.

Also read: Air India to buy 470 planes from Airbus, Boeing; Modi hails ‘landmark deal’

But isn’t hailing business success of private companies different from the government trying to own and run companies? It is. When V Krishnamuthy built up Maruti, Steel Authority of India and Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd, these were owned by the government but were run as efficient commercial operations. Ditto for DV Kapur and NTPC. Government ownership does not necessarily mean government meddling in operations.

State-driven marketing

But the dictum, ‘it is not the government’s business to be in business’, is a sweeping rejection of any role for the government in the conduct of business, not just of ownership. Governments routinely lobby for deals for their national champions, and carry their representative around in high-level delegations to foreign countries. If that is not state-driven marketing, what else is it?

In the land of the free and home of the brave, which supposedly exemplifies business untainted by government interference, defence procurement led to the setting up of the most lucrative segment of business known to mankind. Silicon Valley came up essentially through the activities of professors, graduates and graduate students of Stanford University setting up companies to supply the high-tech gear specified by America’s defence establishment, with liberal upfront funding out of the defence budget.

The Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has a fair claim to having funded and triggered the invention of the Internet. Moderna, which, along with Biontech, the small biotech company in Germany founded and run by Turkish immigrants, created the messenger-RNA vaccines, is a creature of DARPA.

In India, we treat universities as teaching shops, with a few honourable exceptions, sticking to the tradition created by the colonial government. In the US, Britain and most advanced nations, universities receive a sizeable share of state funding for research and development, and universities serve as centres of production of new knowledge.

Commercialising knowledge

Some of the knowledge is amenable to immediate commercialisation, with a little bit of tweaking. The tweaking is done by companies, who file patents and make money milking the intellectual property they claim as their own. The technology of the touchscreen all of us are familiar with and smear with sweat, food and drink left over on our hands after we wipe our mouth, face and other parts of the anatomy was developed in a university department. A gadget maker only had to figure out how to make use of it on a phone.

Of course, this is not to deny that private companies make huge investments in R&D. AT&T’s erstwhile subsidiary Bell Labs has produced nine Nobel prizes and four Turing prizes for research leading up to things like the transistor and laser. Some companies invest as much as a fifth of their turnover in R&D. In India, of course, companies invest in market research and pass it off as R&D eligible for a tax concession.

But that does not mean that governments do not play an active role in business. In the run-up to and during the Second World War, the US government set up or took over countless companies to produce arms and armament, and later privatised them. During the global financial crisis, the US government took over General Motors, to rescue the company from oblivion, took over or part-funded banks. So did governments of other rich countries. Once things stabilised, the government sold its stake to investors and made good profits.

When Oracle found it difficult to take its acquisition in India, i-Flex, private, the US government lobbied the Indian government to change the rules to prevent a handful of holdouts from obstructing the will of the majority of shareholders, and enable delisting of a company after a threshold proportion of shareholders have sold their shares to the acquirer.

It is not just when a foreign government makes a fatal corporate transgression, such as nationalisation, that a rich-country government, to which the erstwhile owners of the nationalised company go crying, takes decisive action, such as when the Central Intelligence Agency initiated a coup against the democratically elected government of Iran that had nationalised the Anglo Iranian Oil Company.

Government’s business

Such defence of corporate interests, followed up with diligent efforts to stamp out, including by physical elimination, the burgeoning influence of Communists among Iran’s democrats, arguably aborted democratic modernization in the most advanced part of the Islamic world and gave birth to the Islamic theocracy of Iran.

Boeing found the confidence to do largescale sourcing from India only after the Indo-US nuclear deal was signed, once again underlining the nexus between politics and commerce. Business, it appears, figures quite prominently in the government’s business.

The short point is that simpleminded ideological prescriptions of untouchability between the state and business deserve to be rejected with contempt, while maintaining healthy scepticism of government meddling in corporate affairs.

(TK Arun is a senior journalist based in Delhi)

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal)