The Quad has the ability to bark, but can it ‘bite’ China?

Seventeen years after the four countries—India, USA, Japan and Australia—came together to help victims in the aftermath of the tsunami, the Quad is again trying to get its act together to take on a tsunami of another kind—the slow but sure rise of China as a superpower and the challenges that it poses for the Asia-Pacific region.

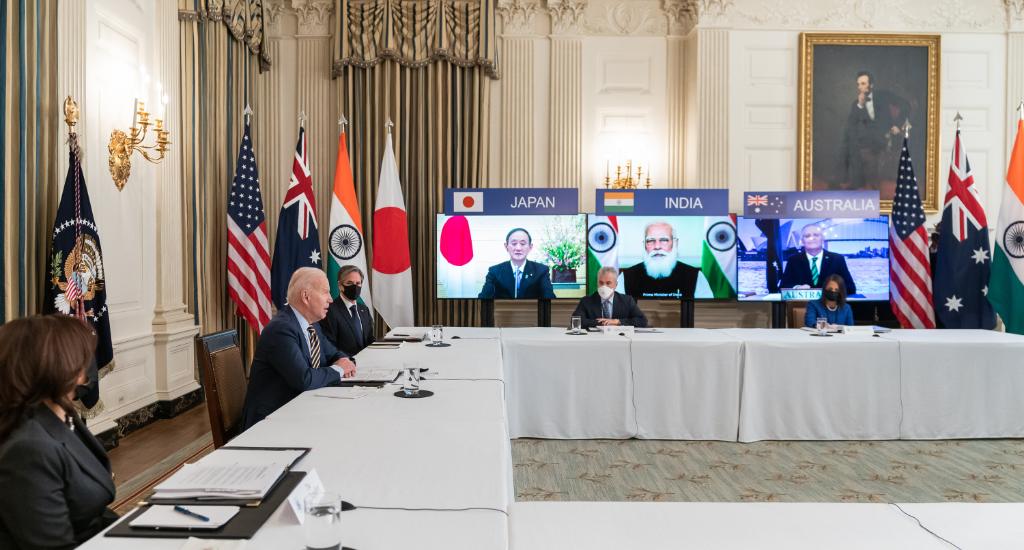

On March 12, when the heads of state of the four countries met as part of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (or, Quad), for the first time, there appeared a sense of urgency in ensuring that it would not remain just yet another grouping but something more substantial.

A statement issued at the end of the summit on Friday did not name China and instead said the Quad nations were “united in a shared vision for the free and open Indo-Pacific”.

“We strive for a region that is free, open, inclusive, healthy, anchored by democratic values, and unconstrained by coercion,” the statement said.

China focus

Reports quoting a briefing by US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said the summit did discuss China’s aggression on the Indian border, its coercion of Australia and Beijing’s harassment around the Senkaku Islands.

The decision to jointly make Covid vaccines and develop 5G and other latest technologies was an indication that together the Quad nations would attempt to make a difference on the ground in areas that may not be political but which could be equally crucial in taking on Beijing.

Also read: Quad’s summit sends warning to China: ‘Will counter threats to Indo-Pacific’

The symbolic value of the meet was not lost on China, the purported target of the new grouping. A spokesperson in Beijing said they hoped it would not turn into a political bloc that would target third-party countries.

Each of the Quad four has a deep grouse against China. India finds itself hemmed in by China on the boundary issue. Since April 2020, tensions have been high between the two across the western and eastern sectors of the Himalayas—in Ladakh and Arunachal.

The recent disengagement in Ladakh has managed to bring down the heat somewhat but there is no saying when the issue will crop up again.

In the case of Australia, since 2017 there has been a downslide in relations with China over Beijing’s suspected attempts to interfere in its internal political processes. Australia was the first to ban Huawei, in response.

Tensions took a serious turn in May last year when Australia demanded that the origins of the Coronavirus pandemic in China be investigated by an international body. This has led to China cutting down on Australia’s beef imports and levying tariffs up to 80 percent on barley imports and 200 percent on wine. For Australia which depends on China for 35 percent of its exports, it is a big hit.

An historic meeting for India, the United States, Japan and Australia – the first ever leaders’ meeting of the Quad.

For us, this meeting is about how we keep Australia and the Indo-Pacific region we live in safe, stable and secure.

🇮🇳 🇺🇸 🇯🇵 🇦🇺 pic.twitter.com/Uk40KccJTJ

— Scott Morrison (@ScottMorrisonMP) March 12, 2021

Japan, in the last few years, has found itself in the thick of a dispute over islands in the South China Sea that it long considered its own. The key Senkaku islands (or, Diaoyu in Chinese) is among the foremost and the Chinese have made no secret of their irredentist intentions vis a vis these territories.

As for the United States, the newly elected President Joe Biden who has systematically been dismantling decisions taken by his predecessor, in a rare move, followed up diligently what Donald Trump started in his tenure -— to take Quad to a higher level of engagement.

The reason is obvious: the US deep state sees China as a long-term political and economic threat, as can be seen in key sectors of the telecom sector including the massive advancements in 5G connectivity and the domination of Huawei across the world.

‘Proof of pudding’

The Quad, is therefore, poised at an interesting intersection at a time when international groupings suffer from a sense of ennui, or a state of Weltschmerz, especially since the end of the Cold War and localisation of conflicts everywhere.

In most cases various groupings have not been able to make much headway as there are disputes among the countries that make up each group, eclipsing the larger purpose.

The SAARC is mostly stagnant for all practical purposes due to the endemic rivalry between India and Pakistan. So is BRICS, in which India and China are members.

The Quad, it may be recalled, came about informally after the tsunami in 2004 and was credited with a level of cooperation amongst the four navies that reportedly proved a major help to the thousands of victims in the Indian Ocean region.

Also read: UK criticises China for violating Sino-British Declaration

Three years later, Japan’s then prime minister Shinzo Abe re-ignited the group in response to the growing threat the country faced from China over disputed islands in the South China Sea. After a joint military exercise and a round of dialogue, the group again turned dormant until Trump pushed it into activity in 2017 following rising US tensions with China.

The Quad’s Achilles Heel, or its inherent weakness, is the bilateral relationship each of the four has with China. In 2008, for example, Australia sacrificed larger interests and temporarily withdrew from the Quad to improve its bilateral relationship with Beijing.

India too has exercised great caution within the Quad and has remained circumspect in not naming China as a transgressor on its border, instead preferring to couch it in general terms around peace and asking that countries play by internationally-recognised rules.

As the cliché goes, “the proof of the pudding is in its eating”. So how well the Quad performs will entirely depend on its agility of response and its impact on any issue concerning China that is likely to come up sooner than later.

Optics and signalling of purpose, as in a summit, are important from the point of view of posturing, but may not amount to much when real action is called for. On this, the jury is out on how effective the Quad will eventually turn out to be.