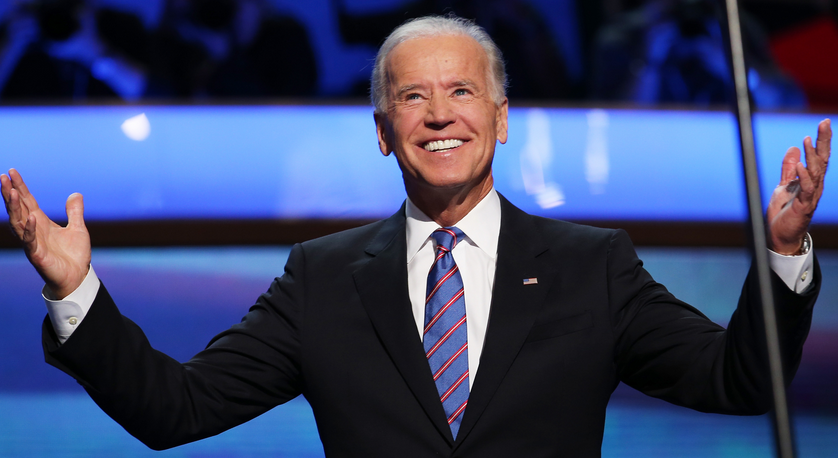

Return of Big Government under Biden good news for the world

When America sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold. That facetious expression — a 20th century adaptation of Napoleonic Europe’s “when France sneezes, all of Europe catches a cold” — not just describes the consequence of large inequality but also intones our inherent dislike of inequality. But inequality can produce occasional boons, too.

When America and Europe caught an unusual cold last year, which galvanized the fastest vaccine development in history: in one year’s time, multiple vaccine candidates against SARS Covi2 were created in multiple laboratories, run through the three stages of clinical trials to establish safety and efficacy, and granted approval for mass deployment. Vaccine development resulted from advances in biotechnology, no doubt, but also from billions of dollars of government grants and pre-purchase commitments.

Also read: Good news for Indian IT: Biden allows Trump’s visa ban to expire

Tax reform

Another pandemic after-effect is going to be tax reform. Big government is back in fashion in America. And when the world’s most powerful nation, with decisive clout in the institutional arrangements that enable the global economy, decides to spend big and tax big, all governments around the world stand to garner additional tax. That is because American efforts to squeeze out additional tax money from the giant corporations headquartered in that country cannot succeed without plugging some of the holes through which the tax liability of giant corporations escapes the grasp of national governments.

Business today is global. Advances in human understanding of the laws of nature and the properties of materials take place in universities and specialized labs in the rich nations. These are converted into business propositions in corporate R&D centres, many of them in Bangalore and Hyderabad. These are then engineered into products and services back in the home countries of the world’s multinationals, outsourced to the supply chains that straddle the world but crisscross Asia in particular, before being sold across the world. The value chain of a single product can enmesh dozens of countries.

Tax havens

Business might be global, but accounting and taxation are done at the national level. So, how much of a company’s value is generated in each country, determining how much of it is liable to taxation in that jurisdiction, is a function of where these multinationals want to report most of their income. Surprise, surprise, they choose low-tax jurisdictions, the so-called tax havens with ultra-low rates of corporate tax, the Bahamas, Ireland, the Netherlands as the sites where the bulk of their income accrues.

Of course, this calls for fancy accountants and corporate lawyers, to structure corporate ownership in different layers in different parts of the world and ownership of profit-making assets within those layers of corporate holding. For example, intellectual property might be developed in Silicon Valley, but transferred to a subsidiary in the Bahamas and licensed to production units across the world, so that the royalty will accrue to a tax haven. Such structuring calls for work. That is why the Big Four of the accounting world exist: PWC, E&Y, KPMG and Deloitte.

Tax planning

When the small guy cuts corners with the income tax he is liable to pay, that is tax evasion. He doesn’t know, or have the means to, take advantage of all the loopholes built into the tax law to shift from illegal evasion to wholly legal tax avoidance. The process of avoiding tax respectably is called tax planning.

Of course, this hurts the fiscal capacity of national governments. They try to claw back some of the tax on the value the multinationals generate in their jurisdictions, with better transfer pricing norms, more rigorous reporting norms and greater capacity in the tax department. It has been a losing battle for countries of the developing world. The academic smarts, the training and the motivation flowing from fancy remuneration of the tax planners keep them a step or two ahead of the taxman.

This would have continued merrily, but for the backlash against globalization in the rich nations. Many jobs are lost to trade with, and outsourcing to, the developing world. At the same time, rich country businesses grow ever richer, with ever-growing access to global markets, global talent and global capital. People begin to revolt against globalization. Unions and the working masses shift allegiance from their traditional political parties to populists who promise to bring their jobs back and make their nations great again. Populists have no animus towards Big Business but lack coherent policy and can destabilize the global arrangements that allow Big Business to become Bigger Business.

Paradigm shifts

Therefore, it is in the rational interest of Big Business to give globalization a human face, spend money on social safety nets, on reskilling of blue-collar workers, on community colleges and on cutting edge new businesses that would absorb some of the human detritus of the world that globalization has demolished — laying out acres of solar panels, for example, would call for a lot of screw-turning, nut-tightening muscle power — as well as generate new jobs that demand higher level skills.

Crises serve as the occasion for paradigm shifts. Ever since Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher championed the message that the government is the problem and not the solution to economic woes, the Anglophone world had espoused an ideology that made a virtue of shrinking the government.

This had not been the mainstream economic philosophy of the United States. From Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal and the government’s takeover and funding of large swathes of American industry for the war effort during World War II, through Lyndon B Johnson’s Great Society, Americans had been comfortable with the idea that the government could and should play a major role in public life. The Cold War-induced spurt in government spending on research and development, the space programme, creation of the Internet, Defence Advanced Research Program Agency (DARPA)’s role in precipitating an electronics and an information technology industry in Silicon Valley — in all this, few Americans saw the government’s hand as meddling hindrance.

It took the period of oil shocks, sustained inflation and the rise of the Chicago school led by Milton Friedman in the 1970s to lay the groundwork for budget deficits and governments that cause them to be seen as the problem.

The 1980s saw Reagan with his tax cuts, talk of shrinking the government and restraining of the government that remained to areas like defence. The collapse of the Soviet Union in the beginning of the 1990s seemed to confirm the undesirability of the big state. General government spending in the US hovered around 38% of GDP, however, close to although below the 40% of GDP threshold of European economies. In India, where Modi, too, tries to make a virtue of minimum government, government spending as a proportion of GDP struggles to reach 27%. Margaret Thatcher brought down public spending as a proportion of GDP from 44% to 40%, only to see it go up again after her time.

Financial crisis

The Global Financial Crisis saw governments step in to save the economy, bail out banks, take over large industrial giants and re-privatise them later. President Obama’s rescue package for the economy that entered crisis on his predecessor George W Bush’s watch cost well under $1 trillion of government spending. In contrast, President Trump spent $4 trillion during the pandemic, mostly on pandemic relief. Now, President Biden has already got approval for another relief package of $1.9 trillion and is negotiating an infrastructure spending package, dubbed the American Jobs Plan that would be worth $2 trillion at the least.

The need to outcompete China, the imperative to upgrade infrastructure — the US ranks 13th in the infrastructure pecking order of nations — the need to move to clean energy to combat climate change, produce more and better quality jobs, create new technologies, support hitherto deprived communities, relocate critical supply chains back to the motherland, motherhood and apple pie all are sought to be bundled into the American Jobs Plan. Biden would like to leave his mark on American history for being something more than Not Trump.

Raising tax revenues

To pay for this infrastructure splurge, the government wants to raise tax revenues from companies. It turns out that 90 of the America’s Fortune 500 pay zero tax in the US. And the average amount of tax paid by companies is 7% of profits. This is what has prompted the US government to propose that companies should pay a minimum 15% of their profits as tax.

If the US seeks to enforce such a tax unilaterally, companies would move to other jurisdictions. Therefore, all countries must agree to a minimum rate of tax on corporate profits. Hence Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s address to the gathered finance ministers at the International Monetary Fund’s Spring meet seeking global cooperation in taxation.

This melds in with the rich country club OECD’s plan to end Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) by multinational corporations. Under Trump, the US had refused to engage with such multilateral efforts. The Biden administration would be willing to play ball.

If the outcome of such efforts to end BEPS is a system of taxation in which multinational companies pay a minimum rate of tax, and apportion that amount to each jurisdiction in proportion to the value added in it, that would be a major step in making global integration work for everyone, and a boost to tax revenues for all countries, including India.

When elephants dance, it is said, the grass gets trampled. At times, when the big guys rumble, they clear the weeds and prepare the ground for wholesome shoots to grow and bear fruit. America’s readiness to shed its fear of Big, Bad Government promises to be one of those happy occasions.

Also read: Biden has ambitious plans for America, but will they really work?