Hindi MBBS will make sense only after ensuring English proficiency

English cannot be ignored as physicians will need a link language to update their skills; a successful propagation of Hindi in medical education will require prolific translation of works in English to the regional language and evolution of public discourse in the regional language

How sound is the move to teach the course leading to a medical degree in Hindi? That depends — just as the answer to the question whether it is sound to swim across the Yamuna. It depends on whether you have learned to swim, how wide is the stretch you plan to swim, and how polluted it is.

There is no reason why, if the Japanese, who number some 13 crore, can study and pursue research leading to a Nobel prize in the Japanese language, Hindi speakers, whose tribe is four times as large, should not be able to learn anything they want in their mother tongue. That is a legitimate aspiration. The point is to put in place the preconditions that would make that effort a success, rather than a comedy with tragic consequences.

Closing eyes to English won’t help

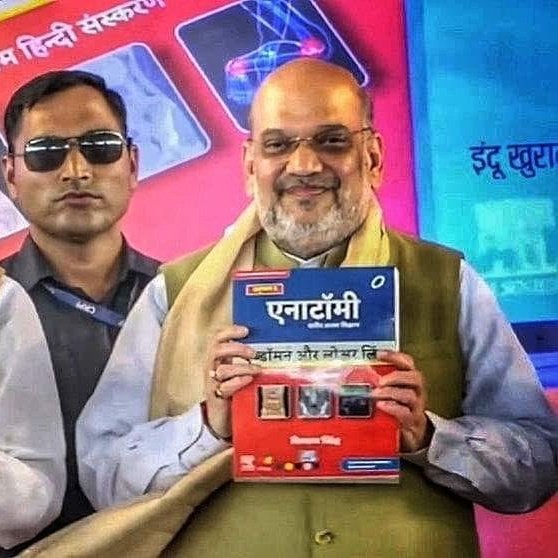

The government at the Centre and some state governments are keen to train would-be doctors in Hindi. Three Hindi textbooks have been launched for the MBBS course, with much fanfare. However, that alone cannot define the success of an Indian language in higher education.

A doctor who gets an MBBS degree might aspire to study further, acquire specialised training in surgery or a branch of medical practice. She might aspire to do her MD or PhD in a part of the country where Hindi is not the medium of instruction, or go abroad to practise. If all she knows is Hindi, she would struggle in her profession.

A doctor will turn into a danger to society if she does not update herself with the latest developments in medical knowledge and pharmacology. New side-effects for people with a particular condition might be identified, as also new drug interactions, not to speak of new therapies altogether. That means she must read medical journals on a regular basis, and follow regulatory advice. Journals and regulatory advice should also be available in Hindi or the doctor should be able to read English proficiently.

Also read: MP doctor uses ‘Shri Hari’ instead of Rx in prescription as govt bats for Hindi

English remains a link language for most of India when precision of articulation and consensual understanding of the meaning of a phrase matter. For interpreting the Constitution, for example, English remains imperative, as of now — people across the country should be able to understand what is said, and understand the same thing when they understand.

Regional languages need more translations

The prerequisites of learning courses of advanced learning in Indian languages is a paradigm shift in the teaching of English at school, so that every child, in whichever medium they study, becomes proficient in English — spoken, as well as written English — as well as in their mother tongue and, possibly, one other link language of the region.

Further, there has to be a culture of prolific translation of works in English to the regional language and vice versa. For specialist registers of medicine, the law and accountancy to be developed in Indian languages, enough of the public discourse involving these subjects must evolve in these languages.

For a student to learn medicine in Hindi, it is not enough for a mere three textbooks to be translated into Hindi. Assorted books in subjects ranging from biology to chemistry, physics and statistics would need to be available in translation, at varying levels of complexity, from the elementary to the advanced.

Translation across Indian languages and from English to Indian languages and from Indian languages to English must become routine and bountiful. This is essential for Indians to appreciate the fine literature produced in Indian languages other than their own, and to be in touch with their cultural heritage as well.

‘Caste system’ in medicine

If, without putting in such hard work, we introduce Indian language degrees in medicine and engineering, the result is likely to be counterproductive. There would be a caste system among physicians. For example: those trained in English and those trained in Indian languages, with patients inclined to treat the ones trained in English as the real doctors and the latter as state-anointed quacks, lowering the image of both the state and the medical profession.

Also read: Hindi not competitor, but a friend of all regional languages: Amit Shah

Let us understand that Isaac Newton wrote Principia Mathematica in Latin, and that all of Europe learned their medicine in Latin. Gradually, when the different European nationalities developed and their languages gained complexity and precision in their broad-based engagement with reality, education at higher levels embraced the bulk of the population, and also shifted to the common, spoken language of the region, even when many technical names were retained in Latin.

The study of Greek and Latin continued as elite persuasions, while the rest had access to the best of European learning in their own language through translation. An Englishman could study Hegel in English and a German could read Hume or Voltaire in German.

By the time quantum mechanics was developed, Paul Dirac wrote in English, and the trio of Bohr, Heisenberg and Pauli, in German. They understood each other because of their acquaintance with the others’ language and because of translations.

If we aspire to make our higher education a realm that advances knowledge, rather than one of coming to grips with pre-existing knowledge, we need not just advanced translations but also proficiency in several languages among our academics, most of all in English.

Also read: How Hindi imposition affects other Indian language speakers

If we want to teach our doctors their medical syllabus in Hindi, let us teach them, those who would translate microbiology and bioinformatics into Hindi, and these translators’ teachers, proficient English beforehand. Otherwise, the entire exercise would become a sham.

(TK Arun is a senior journalist based in Delhi)

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal)