Curbing inflation is RBI’s job; 2022 rate hikes are too little, too late

The central bank should have raised the repo rate when inflation crossed the 4% mark in 2021, but it remained inert until inflation zoomed to 7.79% in April 2022

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) website proudly proclaims the following as its preamble: “…to regulate the issue of bank notes and keeping of reserves with a view to securing monetary stability in India and generally to operate the currency and credit system of the country to its advantage; to have a modern monetary policy framework to meet the challenge of an increasingly complex economy to maintain price stability while keeping in mind the objective of growth.”

It has been precisely adopted from the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. So, no one can have any doubt about the primary objective of the RBI — it is to maintain price stability. Also, no one else can be responsible if price stability is not maintained in the country.

Analysis | Bank privatisation: The key parameters the RBI did not talk about

In a free economy, there cannot be any fixed price for any goods or services, and the price cannot be static. Hence, it becomes necessary also to define what price stability or monetary stability means. Therein comes the responsibility of the central bank in maintaining inflation within a particular band.

A grave error

The RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is mandated to keep CPI (consumer price index) inflation at 4 per cent, with a variation of plus/minus 2 per cent.

So, why has a plus or minus variation of 2 per cent been permitted instead of fixing a definite upper limit? That is because while various micro- and macro-economic factors operate, including cross-border inflow and outflow, some action time may be required to bring the inflation rate back to the permitted level. Hence, some elbow room has been provided with a plus or minus 2 per cent variation.

It means that when inflation crosses the 4 per cent threshold, it is time for policy measures. That is where the central bank’s responsibility comes in.

Opinion: Rate rise by sleight of hand: Monetary Policy says bye to easy money

But the RBI did not act in time to contain inflation, as the following analysis will demonstrate. Instead, it has been accommodative for an unduly long time and made a grave error in its anticipation of inflationary pressure.

RBI and the repo rate

The annual retail inflation rate for 2019 was only 3.73 per cent. But, in 2020, it climbed to 6.62 per cent. In 2021, it dropped slightly to 5.13 per cent. Hence, in 2021 itself, it had crossed the limit set for the RBI.

When we analyse month-wise inflation for 2020, it was as follows from January to December: 7.6%, 6.6%, 5.8%, 7.2%, 6.3%, 6.2%, 6.7%, 6.7%, 7.3%, 7.6%, 6.9%, and 4.6%, respectively.

In 2021, it was as follows: 4.1%, 5.0%, 5.5%, 4.2%, 6.3%, 6.3%, 5.6%, 5.3%, 4.3%, 4.5%, 4.9%, and 5.7%.

When the inflation rate crossed 6 per cent for 10 months in 2020, the RBI should have adopted policy measures. And raising the repo rate is a standard measure to contain inflation. Let us see how the RBI was tinkering with the repo rate during this time.

The above chart makes it clear that the RBI was reducing the repo rate for nearly two years since 2018. On May 4, 2022, it reversed the trend by increasing the repo rate marginally by 40 basis points.

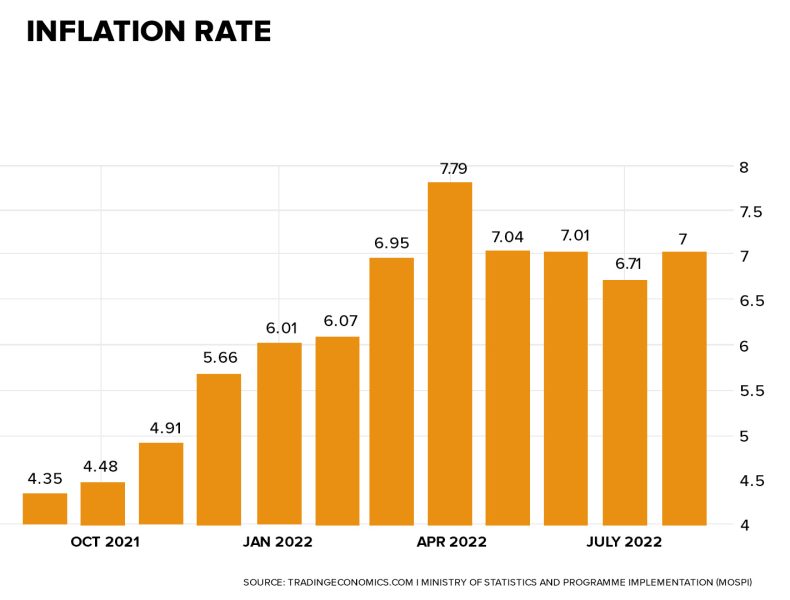

Now, the question arises, why did the RBI fail to act in 2021, when the inflation rate was above the 4 per cent limit through the year? The RBI woke up from its slumber only after seeing the inflation rate rise to 7.79 per cent in April 2022. (See graph below)

Too little too late

Milton Friedman famously said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

The RBI increased the repo rate by 50 basis points on September 30. While doing so, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das said that even though the nominal-policy repo rate had been raised by 190 bps by then, the policy rate adjusted for inflation trailed 2019 levels.

Also read: After Covid and Ukraine war, economy in eye of a new storm: RBI Governor Das

This mindset reveals that the RBI considers borrowers’ interest more important than performing its mandatory role. We may also be tempted to ask the RBI Governor why bank depositors are not compensated for inflation and how they are allowed to forego their purchasing power.

More trouble ahead

The problem is not yet over, as the RBI has made the following projection of inflation: FY23: 6.7 per cent; Q2 F23: 7.1 per cent; Q3 F23: 6.5 per cent; Q4 F23: 5.8 per cent, and Q1 F24: 5.0 per cent.

Opinion: Bad bank is a bad idea; it’s brushing balance sheets under the carpet

Das has tried to wriggle out of his responsibility by making the following statement: “In the last two-and-a-half years, the world has witnessed two major shocks — the Covid-19 pandemic, and the conflict in Ukraine. Now, we are in the middle of a third major shock, a storm arising from aggressive monetary policy actions and even more aggressive communications from advanced-economy central banks.”

As said earlier, inflation is a monetary phenomenon, and citizens expect monetary response from the RBI. Yes, only monetary response and not political response.

(The writer is a retired banker)

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal)