CAA: Time India wakes up to the mistakes of other nations

The protests against the latest amendment to the Citizenship Act, 1955, stand out for their spontaneity, the absence of any identifiable leadership and mark the first time that a decision of the Modi government has met with popular resistance of this magnitude.

The protests against the latest amendment to the Citizenship Act, 1955, stand out for their spontaneity, the absence of any identifiable leadership and mark the first time that a decision of the Modi government has met with popular resistance of this magnitude.

There was hardly any opposition when Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced demonetization in November 2016 despite all the troubles it caused to people across various economic strata, or when GST was implemented in the most ham-handed manner in July 2017 — the effect of which the industry is still barely recovering from — and in the second term, the suspension of special status to Kashmir in a manner that was controversial and open to legal challenge.

While all these decisions have been contentious, the near-absence of any opposition was probably interpreted as a blank cheque to the government to take any decision, however controversial. But, that has been brought to a halt by the sustained opposition to its move to amend the Citizenship Act (CAA). The reason is obvious. This time around the government appears to have hit where it hurts – differentiating people based on religion, an anti-secular move that directly affects the basic structure of the Constitution.

Supporters and apologists for the amendment point out that there are just around 30,000 non-Muslim migrants who stand to benefit from the amendment; that it does not come in the way of Muslims who might want citizenship on the grounds of religious persecution – only that they would need to wait for 11 years for it; and, that the CAA has nothing to do with the National Register of Citizens (NRC) exercise.

Also read: CAA-NRC: The ‘ploy’ to divide masses is actually uniting India

But the point that is being missed, conveniently or not, is that a law has been enacted which centres around the religion that a person belongs to. The law, as per the CAA, will treat you differently if you are a non-Muslim and if you are a Muslim. This is untenable under Article 14 of the Constitution which stands for equality irrespective of one’s belief, religion etc.

Another argument by the CAA supporters is that Article 14 applies only to Indian citizens. Since those asking for citizenship are illegal migrants Article 14 does not apply to them. In reality, this is not the case, as Article 14 clearly states all individuals will be treated equally within India. It does not matter whether a person is a citizen or not.

The CAA has effectively touched a raw nerve. If this law is allowed to stand in the current form, it implies a significant dilution of India’s secular credentials and could be quoted as a precedent in future legislations to the detriment of minority communities.

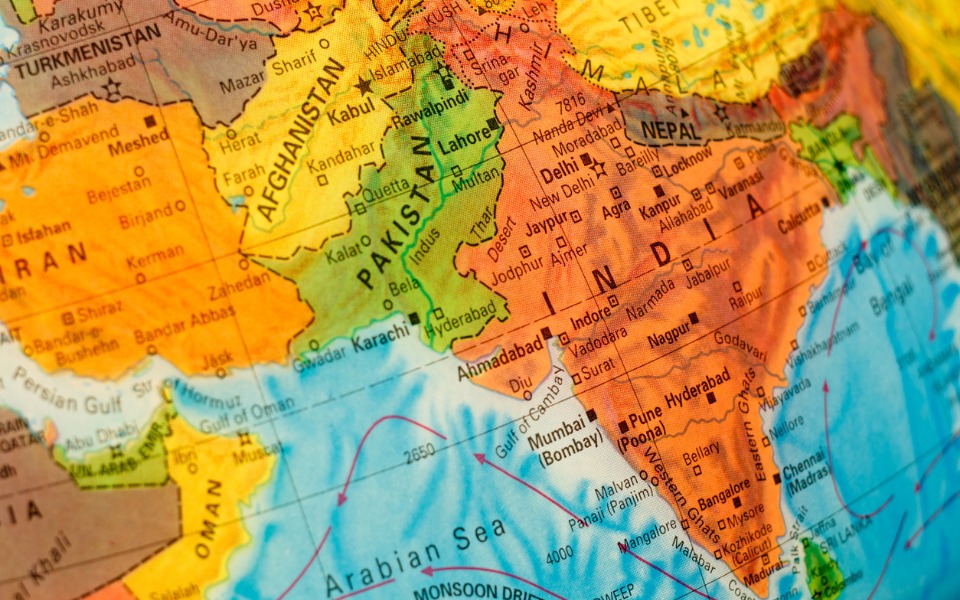

World over, nations have come to grief by meddling with basic tenets of their governance or Constitutions. The closest example is Pakistan where the Punjabis attempted to browbeat the Bengalis in the process opening up ethnic and linguistic fault lines between the West and East of the country leading to its eventual dismemberment in 1971. The fact that they shared a common religion – Islam – did not help.

Also read: On India’s streets, youth push back BJP’s politics of hate, fear

In Rwanda, in 1994, the minority Tutsi community was the target of a genocide by the majority Hutus over long-standing resentments that boiled over following the assassination of President Juvenal Habyarimana. On the face of it, the Tutsi and the Hutus looked the same and there would have been no way of picking out one from the other. But, a system of national identity cards which specified which community they belonged to made it easy for the Tutsis to be singled out. In 100 days, from April 7 to July 15, an estimated 800,000 people, mostly Tutsis were decimated.

Sri Lanka, which became independent in 1948, opened up a historic fault line between the ethnic Tamils and Sinhalese eight years later. In 1956, the Sinhala Only Act was passed which turned Tamils overnight into second class citizens. Teaching jobs, top positions in the administration and in the military were taken over by the Sinhalese triggering widespread anger among indigenous Tamils.

It was this legislation that eventually led to a section of the Tamils grouping together to fight for a separate Eelam. For the next 53 years, the nation was wrought by separatist violence, assassinations and turmoil that almost tore apart the nation. Attempts were made to alter some provisions later to make the law more inclusive, but the damage was done and a violent civil war wrought havoc on Sri Lanka until the defeat of the LTTE in 2009.

In the Balkans, Yugoslavia under Marshal Josip Tito was a powerful nation and part of the socialist bloc until 1980 when he died. Over a decade later, the rise of nationalist politics symbolised by leaders like Slobodan Milosevic opened up ancient ethno-religious fault lines completely breaking up the six republics that once formed a united nation. Christians against Muslim, Serbs against Bosnians, Croats against Serbs… so on and so forth. The break up spread over a decade starting in the early 1990s was bloody, gruesome and threw up incidents like the Srebrenica massacre that reverberate the world over even now.

Also read: Resistance to CAA shows how to deal with BJP’s Gujarat model of conflict

These are examples that no nation would wish on itself. It would be worthwhile to remember that these have happened over the last 50 years to countries that would have never had an inkling of the fate that was in store for them. The commonality among the reasons lies either in the realm of religion or ethnicity, which clearly show these are emotional areas that need to be handled delicately.

India’s Constitution makers and leaders in the aftermath of Independence and the lessons learnt from the experience of Partition were far-sighted to understand the importance of the concept of “live and let live”.

The Constitution, as one can see, therefore allows all communities, religions and ethnic groups equal breathing space under the umbrella of an inclusive framework. This has won admiration from the rest of the world which in 1947 had doubts over the survival of the nation given the turmoil that accompanied independence.

India, incontrovertibly, stands for a secular democracy even if some sections within India have a problem with it. It is in this context that the CAA needs to be looked at – as a legislation that seems to threaten a fundamental tenet of the nation, and hence the sustained protests.