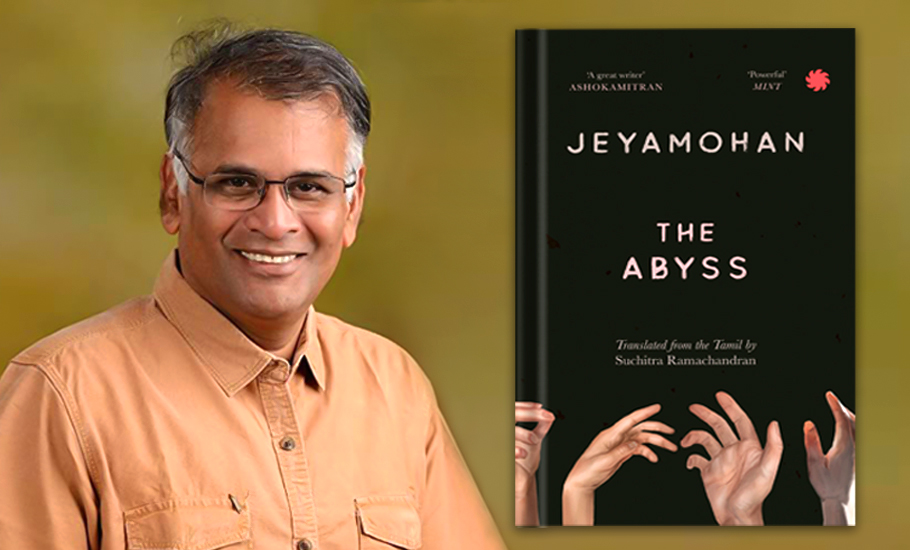

Jeyamohan interview: Ezhaam Ulagam, or The Abyss, is a spiritual inquiry into beggars’ lives

The writer and his translator talk to The Federal about the novel, modern Tamil literature, Perumal Murugan, and more

Jeyamohan, known for works that delve deep into the intricacies of the human psyche and the depths of emotion while remaining rooted in Tamil culture and tradition, lived as a beggar once, like Malayalam stalwart Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, who wrote that ‘there is an India you discover only as a beggar’. In 1981, at the age of 19, feeling the weight of the world bearing down upon him, Jeyamohan fled from home with a burning desire to renounce the world and become an ochre-robed samiyar.

Though he ultimately returned home and resumed his ordinary life, Jeyamohan’s brief time among the beggars of Tiruvannamalai and Pazhani in Tamil Nadu left an indelible mark on his soul. In the midst of despair and desolation, squalor and suffering, there had been a spark of hope, a flicker of light that refused to be extinguished.

Jeyamohan had seen the resilience and the resourcefulness of those who shared his plight, those who refused to be beaten down by the weight of their circumstances. He had witnessed the power of compassion, the generosity of spirit that could bridge the chasm that separated the haves from the have-nots. And, importantly, the importance of empathy in a world that often seemed to be defined by its cruelty and callousness.

Also read: The arid, defiant world of International Booker-longlisted Tamil writer Perumal Murugan

Jeyamohan’s days as a beggar inspired the writing of his acclaimed novel Ezhaam Ulagam (United Writers, 2003) and shaped his worldview with a deep empathy and insight into the lives of the people existing beyond the margins of society. Adapted into a critically acclaimed film — Naan Kadavul (I am God, 2009), which fetched a National Film Award for director Bala — it has been translated into English by Suchitra Ramachandran as The Abyss (Juggernaut Books).

The Abyss: A cesspit of the grotesque and the disfigured

In 2003, when Jeyamohan (60), who lives in Nagercoil, was on his way to work, he caught a fleeting glimpse of a face on the road that stirred deep emotions within him. Memories of his past as a beggar in Pazhani resurfaced, and the face that appeared in his mind was that of Ramappan, a leprosy-afflicted man he once knew and admired for his admirable qualities of kindness, love, and a strong sense of justice.

Inspired by the image of Ramappan, Jeyamohan felt an overwhelming desire to write about his life, and he immediately set out to write a novel. In just five days, he completed Ezhaam Ulagam, which was launched at the Chennai Book Fair a few days later and has since become a widely acclaimed work in Tamil literature.

Drawing from Hindu mythology’s description of seven underworlds — athalam, vithalam, nithalam, kapasthimal, mahathalam, suthalam, and padhalam — Jeyamohan named the novel Ezhaam Ulagam or ‘The Seventh Underworld’ or paatalam. “That is the unfathomable abyss the people of this novel inhabit,” he writes in the introduction.

Also read: Perumal Murugan’s Pyre, the Booker longlist, and global caste dialogues

Set in Kanyakumari, The Abyss explores the complex moral landscape of human nature through the story of Pothivelu Pandaram, a successful and pious man with a loving family, whose prosperity is built upon a despicable trade: He owns a group of physically deformed beggars whom he employs to beg outside temples, exploiting their pitiable appearance and plight for personal gain. To him, these beggars are nothing but commodities or items to be bought and sold at will.

The novel, which places the reader in the midst of the beggars’ horrifying world, poignantly explores the boundaries of human suffering and liberation. “It is not a realistic portrayal or documentation of their lives. Instead, it is a philosophical and spiritual inquiry into their existence, their value system, and the basic nature of humans,” Jeyamohan tells The Federal. “It’s a quest towards understanding what human values are and if they can be applicable to all human beings,” he adds, explaining his objective in the novel that raises a crucial inquiry: how can the compassionate and god-fearing nature of Tamil people coexist with their apathy towards the destitute?

Through Pandaram, Jeyamohan examines what drives humans to perpetrate cruelty despite their innate goodness. The beggars portrayed in the novel, despite living in abject poverty, possess their own distinct industrial and spiritual lives, and a unique sense of humor. Jeyamohan illuminates humanity’s remarkable capacity to forge its own life under any circumstance. Though the novel is dark and painful, it offers a positive vision of life, says Jeyamohan, adding that he does not see it as a critique of India’s socio-economic system.

The novel boasts of proper world-building and a large part of it flows through the dialect, and humour, says Basel-based Ramachandran, who writes fiction in Tamil and translates between Tamil and English. “Since the novel travels across Tamil and Malayalam languages, translating the wordplay was challenging, but fun to do,” she says.

‘Writing is a meditative experience’

The memory of a real person, says Jeyamohan, is always multi-layered. When the image of Ramappan flashed through his mind, the writer also arrived at several other ‘archetypes’ of the characters that found their way to the novel. One of them is Mangandi Samy, a spiritual person who finds happiness and comfort in the cesspit of suffering and cannot bear to live in the so-called civilized world. The beggars, Jeyamohan notes, have their own value system and do not like compassion, which they view as pretension or hypocrisy.

Interestingly, Jeyamohan doesn’t plan his novels in advance. He has no idea what he is going to write until he starts the first line. For The Abyss, he had the image of protagonist Pandaram looking at the stars, and started writing from there. Writing the novel was a cathartic experience. “I had some kind of spiritual rapture while writing it. It was akin to something shuffling inside. It was about misery, but after writing it, I felt like I had gained something.”

Jeyamohan believes that writing is a meditative experience, and one that cannot be remembered when one becomes very sober. He doesn’t force himself to complete novels that he loses interest in, instead choosing to throw them away. It was a matter of pure luck that The Abyss was completed easily and became one of his greatest works.

Popular vs Literary

Every society, Jeyamohan posits, possesses two layers of reality: the popular or common reality known to all and the deeper, more elusive truths that literature endeavours to capture. While some writers focus on the former, Jeyamohan asserts that great literature delves into the latter, illuminating the subtle nuances and complexities of a particular culture. “A popular work will knock at your doors. In contrast, you have to go to a literary work and knock at its doors,” he says.

In Jeyamohan’s estimation, the works of Perumal Murugan, whose novel Pyre, translated by Aniruddhan Vasudevan, has been longlisted for the 2023 International Booker Prize, tend to remain on the surface level of popular culture, appealing to outsiders through their accessible, superficial narratives. For him, a deeper appreciation for a literary work requires an attentive engagement with the culture from which it emerges. “I expect my readers everywhere to come to my work, and try to understand it,” he says.

According to Jeyamohan, the focus of Modern Tamil literature is not on creating social or political realism, but on transcending these limitations and exploring new frontiers in post-modernism. He says his writing reflects this ethos, characterized by its incoherence and lack of a centralized structure, often dismantling traditional literary conventions to create something truly new and innovative.

Ramachandran arrived at Jeyamohan’s work through Purappadu, which is “not just a travelogue, not just fiction, but a modern work in the spirit of Dante’s Inferno – a fiction-laced narrative of a personal, interior journey,” she writes in her introduction. Purappadu is the spiritual precursor to the world portrayed in The Abyss, she tells The Federal. As someone familiar with Tamil culture, she knew what to look out for as a translator. “The more open you’re to picking up influences from what you are translating, the better. You’ve got to be faithful to the feeling and sound as a translator. You have to catch them. You’ve got to be faithful to the emotional arc of the narration. There are bound to be some places where you have to make creative choices. You should not be looking at preserve the ashes, but the fire,” she says.

The arcs of loss and grief

Born in Thiruvarambu, Jeyamohan’s early life was defined by restlessness and a search for meaning. He had embarked on his life as a mendicant at 19 after the suicide of a close friend during his college years had shattered his world, propelling him to abandon his studies and embark on a journey across India in search of physical and spiritual fulfillment.

Fueled by a voracious appetite for literature and a need to support himself, Jeyamohan took up odd jobs and wrote for pulp magazines, his eyes fixed firmly on the horizon. It was during a temporary position at the Telephones department in Kasargode that he became involved with Leftist trade union circles, gaining formative insights on historiography and literary narrative that would later shape his work.

But tragedy struck once again in 1984, when both of Jeyamohan’s parents committed suicide within a month of each other. This devastating loss further unsettled the young writer’s already itinerant lifestyle, and he continued to wander in search of solace. It was not until a chance encounter with writer Sundara Ramasamy in 1985 that Jeyamohan found a new path.

Also read: Viduthalai 1 row: ‘Inspiration’ from Left, credits for Right-wing author

Ramasamy became a mentor and encouraged him to take up writing seriously, a calling that Jeyamohan would answer with fervour. Through loss and struggle, Jeyamohan’s restless spirit ultimately found a home in the written word. “There are two aspects of literature. One aspect is the craft of writing, and the other is the endeavour of living as an independent writer. In the current age divided by political factions, the challenge lies in maintaining a sense of intellectual independence. Survival is often contingent upon one’s loyalty to a particular political faction,” he says. From Ramasamy, he learnt that a writer should be apolitical and independent, free to chart his own course. This ideal of independence is a major undertaking for a writer, one that Jeyamohan embraces wholeheartedly. For him, the mantle of being a writer is a 24-hour calling that pervades every aspect of his life, regardless of circumstance. “To this day, I am following his mission. I am a 24×7 writer, throughout the year. In any situation, I place myself as a writer,” he says.

The epiphany

It was during the early years of his youth that Jeyamohan had a moment of epiphany, which saved him from suicidal thoughts. When he was 24, he found himself walking towards a railway track somewhere between Kasaragod and Kumbla with the intent of ending his life, he writes in the introduction to Stories of the True (Juggernaut, 2022) a collection of short stories translated by Priyamvada Ramkumar, which marks the first English translation of his work.

As he walked towards the railway track, he noticed a worm resting on a leaf, its body glowing as though made of light, with a soul just as radiant. This small being demonstrated how every moment in life holds immense significance, even with the inevitability of death looming. It possessed a unique purpose in the world, one that could not be fulfilled by any other. This encounter was a darisanam, a vision that later transformed into the philosophy that guides Jeyamohan’s life. From that day forward, he vowed to eliminate sadness, bitterness, and resentment from his life.

Through his stories, he says, he wants to create a philosophical universe where we are all part of the global life system, with the right to be happy and self-assured of our lives: “The global system consists of me and the beggar, me and the dog,” he says. To Jeyamohan, Samy the beggar is greater than any multi-millionaire because he is a saint, a liberated person. “A free person is far more superior. I want to create that vision,” says Jeyamohan.

As an itinerant samiyar during his youth, Jeyamohan observed that there were thousands of samiyars and sannyasis, pandarams and paradesis wandering all over India. His life as a beggar facilitated a greater understanding of the human condition, a deeper appreciation of the interconnectedness of all beings. The Abyss is a testimony to that insight. For Jeyamohan’s own spiritual teacher, Guru Nitya Chaitanya Yati, and his teacher Nataraja Guru, begging for their living was an integral part of their spiritual journey — like Adi Shankara and Swami Vivekananda. He writes in the introduction: “They were all begging. They had no identity. I now wonder if it is to them that this country truly belongs.”