Hrishikesh Mukherjee, master storyteller who made us love all things simple

They were characters you would meet every day – the film-obsessed teenage girl, the aspiring youngster in his 20s, or even the family, whose members are at loggerheads. These were the protagonists that the legendary Hrishikesh Mukherjee had in his films, and the ones filmgoers fell in love with.

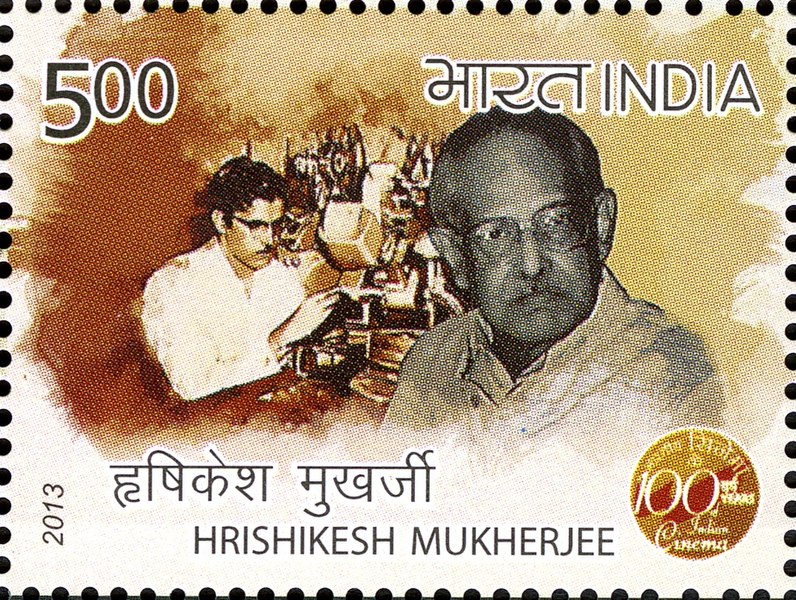

The film editor and filmmaker, who passed away on August 27, 2006, branded his stories with the realistic portrayal of the middle class, peppering it with pure comedy and pioneering an altogether different genre called the ‘middle of the road’ movies.

The beginning

Born on September 30, 1922, Mukherjee began his career as a cameraman and then continued as a film editor in the 1940s. He soon joined the legendary Bimal Roy and worked with him in his masterpieces like Do Bigha Zameen and Devdas. The first film he directed was Musafir (1957), starring Suchitra Sen, Dilip Kumar, and Kishore Kumar. He met with little success.

However, in 1959, Anari, a musical drama, which had Raj Kapoor and Nutan playing the lead roles, catapulted him to fame. His type of work could be divided into two parts—drama and humour. He was probably the most versatile filmmaker in the industry.

At a time when his contemporaries like Nasir Hussain were dabbling in the musical romance genre with Shammi Kapoor or the romantic heroes like Joy Mukherjee and Shashi Kapoor, or when Vijay Anand was alternating between drama and dance grandeurs like Kala Bazar, Guide, and Jewel Thief, Mukherjee introduced women-powered storylines.

Be it Anuradha (1960), starring a lissome Leela Naidu alongside the towering Balraj Sahni in the story of a lonely wife, who yearns for her husband’s attention and love, or Anupama (1966), where a quiet Sharmila Tagore is pitted against the idealistic and poetic hero played by Dharmendra, Mukherjee broke the mould of the quintessential Hindi heroine.

In Aashirwad (1968), he teamed up with the aging Ashok Kumar in the saga of a father yearning to meet the daughter he got separated from when the latter was a child. There is a possibility that this was an extension of the father-daughter relationship he discussed in Anupama. However, the best was yet to come and it was Satyakaam that gave the macho Dharmendra the much-needed artistic break he was looking for. Set in post-Independence India, it depicted how ideals dissipated due to corruption and the euphoria over freedom made way for despair.

Memorable collaborations

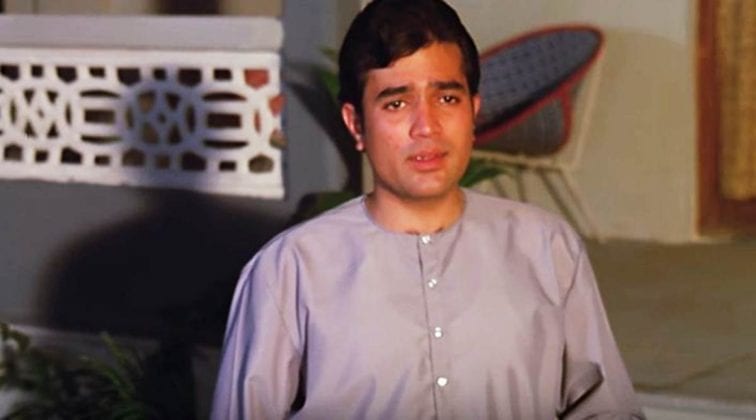

The 1970s marked collaborations with not just actors, but also producers and technicians. Anand (1971) gave the role of a lifetime for Rajesh Khanna, who had already made it to the top and was still basking in the success of Aradhana. The story is about a dying young man who wants to spread happiness and his bond with a brooding doctor whom he inspires to live life to its fullest—a story poignant yet with its own moments of laughter. That was the first of his many successful projects with both Khanna and Amitabh Bachchan, who was just finding his feet in the industry.

The same year, in Guddi, that introduced a fresh and comely Jaya Bhaduri to the Hindi audience, Mukherjee spoofed the film world. The film revolves round an innocent teenage girl who is smitten by a film star and how her uncle makes her realize the difference between true love and infatuation. Guddi was also a rare tribute to the film industry, which takes the audience through the real lives of reel heroes and villains and shows how the industry feeds the innumerable people dependent on it.

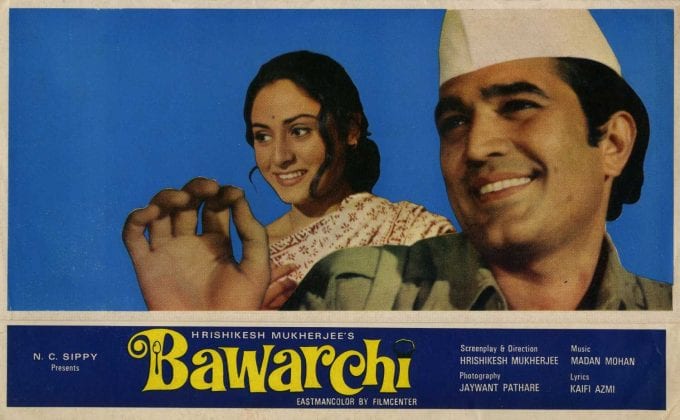

Perhaps the Mukherjee-Gulzar combo was the best among all teams that the industry has seen for several decades in screenplay and dialogue, even as Gulzar was making his own movies around the same time. Never scared of experimenting with stars, he made Khanna play a cook in the 1972 classic Bawarchi, the tale of a squabbling joint family that is united by the cook who connives for their good.

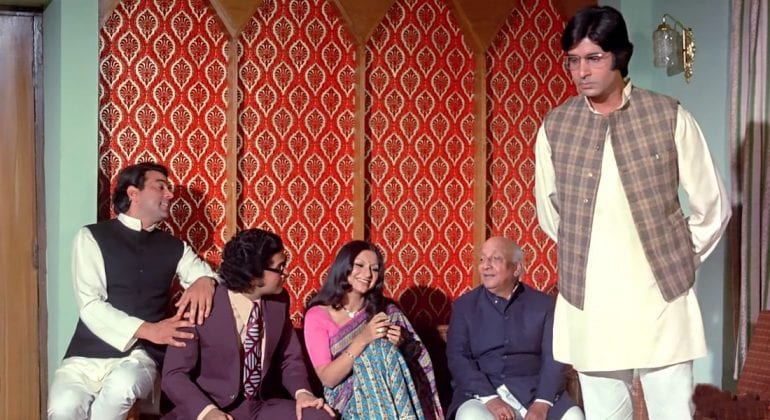

In the multi-starrer Chupke Chupke, Mukherjee perhaps set a new definition for comedy in Hindi cinema. When comedy was either stereotypical or over the top, Mukherjee introduced pure comedy. The 1975 flick had Dharmendra leaving the audience in splits as he went on a shuddh-Hindi spree to impress the condescending Jijaji (brother-in-law) played by Om Prakash. Bachchan took over the second half of the film with his dilemma over wooing the girl who mistakes him for a botany professor, even as he wants to romance her in Shakespearean English.

Chupke Chupke offered a fresh take on the Bachchan-Dharmendra duo which was yet again seen in an action-packed plot of Sholay that released just four months later.

Close on the heels of its success, Mukherjee followed up with Golmaal and Khubsoorat – all of which delved deep into emotions of friendship, family, and love. Golmaal made Amol Palekar’s twin-act and Utpal Dutt’s Bengali-laden Hindi a household favourite, while Khubsoorat reinvented Rekha in a glamorous and endearing avatar as the bubbly beautiful woman who wants to bring in joy to a home run like a military camp by its strict matriarch.

While it was also the decade of filmmakers like Basu Chatterjee, who had his own take on middle-class ambitions in the backdrop of the teeming city of Bombay, Mukherjee’s films had his trademark. They were stories of trust and relationships that ought to be sustained, albeit through a few harmless conning acts.

A master editor himself, he believed in tightly packed sequences and quick cuts. He was ably supported by cinematographer Jaywant Pathare who worked with him for more than four decades and sometimes making a brief appearance like in Abhiman, or finding a mention in Chupke Chupke— in both donning the role of a doctor.

Even as the 1980s saw him make fewer films like the laugh riots Kisise Na Kehna and Rang Birangi, Mukherjee displayed immense variety in his set format of family comedies.

Mukherjee’s brand of cinema or comedy may not strike a chord with the current generation of viewers and his stories may appear banal in the age of adventurous filmmaking. Yet, the current vast body of works probably cannot make up for the largesse of heart his stories had for the subtle and simple. As Anand says, “Zindagi badi honi chahiye, lambi nahi” (life should be big, not long). Neither can they match with his eye for humour hidden in routine acts – much like what Rajesh Khanna says in Bawarchi, “It is very simple to be happy, but it is very difficult to be simple.”