Harsh Mander: ‘State’s failures during pandemic amount to crimes against humanity’

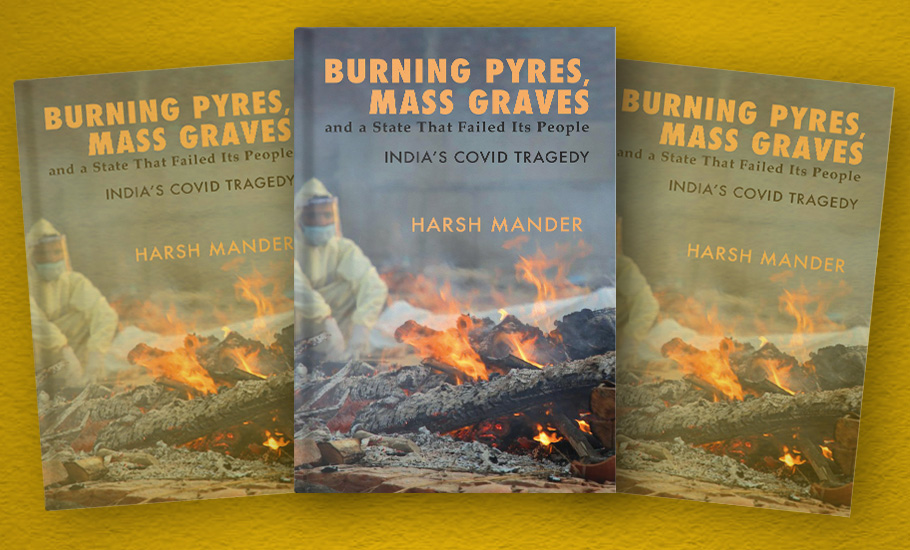

Activist-author Harsh Mander’s latest book, Burning Pyres, Mass Graves and a State That Failed Its People: India’s Covid Tragedy (Speaking Tiger Books), chronicles the devastating impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in India. Divided into two parts, it offers a vivid account of the initial months of the crisis during the summer of 2020, followed by a reflective exploration of the calamitous second wave in 2021.

In the first part, which incorporates his previous book, Locking Down the Poor: The Pandemic and India’s Moral Centre (2021), Mander delves into the heart-wrenching stories of hunger, joblessness, and the exodus of migrants during the lockdown. His ethically charged writing captures the urgency of the moment and the raw emotions experienced on the front lines.

In the second part, his voice takes on a more contemplative tone as he grapples with the horrors unleashed by the second wave. He mourns the burning pyres on city sidewalks, the mass graves, and the systemic failures that denied the people access to vaccines, oxygen, and hospital beds. It is here that he raises crucial questions about the structural deficiencies that exacerbated the crisis, challenging the very foundations of India’s healthcare system.

Mander paints a searing portrait of a nation pushed to the brink and exposes the gaping chasm between the privileged and the marginalised, unmasking the callousness with which the suffering of the working poor was disregarded. He reveals the complicity of those in power, inviting readers to confront the collective amnesia that threatens to erase the lessons learned from this profound tragedy.

Also read: How China is set to reshape global trade, assert geopolitical dominance with New Silk Routes

He also envisions a path forward — a call-to-action grounded in remembrance, accountability, and compassion — and urges us to create spaces for collective grieving and to honour the lives lost, while pushing for transformative policy reforms that address the deep-rooted inequalities plaguing the nation. Burning Pyres, Mass Graves and a State That Failed Its People, thus, serves as both a stark reminder of the perils faced by a nation and a rallying cry for change.

In an in-depth interview to The Federal, Mander shares that the most frightening aspects of India’s experience with the pandemic were the preventable suffering and loss of lives due to the state’s lack of scientific rigour and public compassion. He underlines the indifference of the government towards the working poor, the failures of the healthcare system, and the catastrophic consequences of a highly privatized economy with minimal labour rights and social protection. Excerpts from the interview:

What specific aspects of India’s experience with the pandemic did you find most frightening, and how did these aspects shape the narrative arcs of Burning Pyres, Mass Graves and a State That Failed Its People?

I think most of all it was the realisation that a great part of the monumental suffering, and literally lakhs of deaths, that we saw during the pandemic, could have been prevented had only the state acted with scientific rigour and public compassion.

It was also the evidence of how little the working poor matter to the government, how utterly dispensable their lives are. You callously impose a brutal countrywide lockdown with almost no relief package in a country in which nine out of ten workers are informal workers, most of whom can only eat what they earn each day. Then there was the accumulated consequence of one of the most highly privatised health-care systems in the world, in which eight out of ten doctors work for the private sector, and in which primary health care services are collapsed or absent.

And the catastrophic consequences of a massive labour force with nearly absent labour rights and social protection. And then of course the calamitous second wave where the state failed to ensure the vaccinations, oxygen and hospital beds that could have saved hundreds of thousands of lives. I believe that the failures of the Indian state during the pandemic — of its hubris and oppression in the first wave, and its absence in the second — qualify cumulatively into what amounts to crimes against humanity.

Could you talk about the ethical dilemmas you encountered while documenting the experiences you describe in the first half, and how they influenced your process of writing about the first wave?

When I heard on television the Prime Minister’s announcement of a total countrywide lockdown, I found it hard to believe how indifferent he was to what the consequences of this punishing lockdown would be on millions of the working and destitute poor. There was mass hunger and joblessness breaking out in cities and (more slowly) in the countryside.

I resolved at that moment that I would not obey the lockdown. I would be on the streets trying to do what I could to organise food and also health care. What I saw on the streets, of thousands of people being reduced to the humiliation of hunger and destitution by a pathologically uncaring state, led me to resolve to write the history of this watershed moment of our collective history. A young colleague of the Karwan-e-Mohabbat carried a camera and we made a series of short films of what we bore witness to. And when I came home I would write as the only way to unburden my soul.

Speaking Tiger Books,

pp. 464, Rs 599

And I wrote with the idea of a public duty to bear witness when the state and most of privileged India had looked away. We reached out to Karwan colleagues from around the country, people who came together to respond the countrywide epidemic of hate lynching now turned to the new epidemics of mass hunger, joblessness and the distress march of millions of migrants on the highways. The ethical dilemmas of my writing were less, I think, because we were telling stories of people who we were trying to help in solidarity.

Across the book’s two parts, you offer readers different perspectives and temporal distances. What message or effect were you aiming to achieve through this juxtaposition, and what challenges did you face in balancing the two narrative styles?

Ravi Singh and Nazeef Mollah, my editors at Speaking Tiger, and I discussed and decided to do precisely what you observe. This is to juxtapose the anguished first-person witnessing of the first wave with the more reflective and analytical writing about the second wave. We hoped that the enormity of the largely preventable human tragedy would remain with the reader even as she understood more precisely the specific forensics of where the state went wrong, in which ways, and what it could have done differently.

In the second part, you dwell on the cataclysmic failures of the state to address the second wave. Could you elaborate on the systemic factors or underlying causes that contributed to these failures, and what implications they have for India’s healthcare system?

To begin with, let me underline that some part of what transpired was a “tragedy foretold”. Not just the present government, but governments in the past, have allowed investments on public health to remain among the lowest in the world, with the ruinous consequences for the access of poorer people to decent health care.

Also read: The Last Courtesan review: How a tawaif built a life for herself, and her son

The government could not have changed this suddenly when the pandemic hit. But there is no way it could have risen to the public health care challenges posed by the pandemic unless it nationalised — at least for the duration of the pandemic — the private health industry. Without doing this, the only way that more beds could be “created” for covid care was by diverting beds from other health needs, ranging from childbirth to cancer and dialysis.

For vaccines, the government should have resorted to compulsory licensing well in advance of the second wave; this could have probably averted at least the severity of the second wave, and India could have supplied vaccines to poorer countries in Africa and Asia. Instead the government favoured two private companies which — by their own accounts — reaped super-profits, while delayed vaccination cost an uncounted number of preventable deaths. The story of oxygen shortage is equally culpable. The government had a long window after the first wave ebbed to prepare for expanding the country’s capacity both to manufacture and transport medical oxygen, but it squandered this, and the wages of this was people choking to death outside or within hospitals.

In the book, you emphasise the need to grieve, to create spaces for remembrance and to honour the lives lost. Do you believe this process of collective grieving can contribute to the healing of individuals and communities affected by the pandemic? What role do you envision art, literature, and other forms of creative expression playing in the process of remembrance of all that happened?

I begin my book with a prologue about why I write. I say that I write first of all to give ourselves the spaces to grieve. In the tumult of the pandemic, so many of us could not even give our loved ones a decent funeral and gather those who loved them to collectively grieve. So many corpses were cremated or buried by strangers, or thrown into rivers.

The state is also in stubborn denial of the numbers of people who died in India due to covid. The official death toll is around half a million, while experts believe that the number could be even as high as five million. We must grieve every single life lost, firstly to affirm that every single life lost was of value. And yes, in our grieving there is great space for poetry, music, storytelling and film about this landmark time in the journey of our republic. Anubhav Sinha’s Bheed was a significant effort in this direction.

In your view, what were the key factors that hindered the implementation of effective measures and resulted in such a significant loss of life? What structural changes or policy reforms do you believe are necessary to ensure that such devastating mortality crises are prevented or mitigated in future?

As I said earlier, a major driver for me to write this book was to learn lessons for building a future in which the next time a humanitarian health emergency of this kind embraces us, it should not have these devastating consequences. I speak at length in the book about more basic structural and policy reforms that are imperative to prevent the recurrence of such an immense collective tragedy the next time a new virus invades the planet.

Let me speak of a few. First, hugely raised investments in public health, with focus on primary and secondary health services and community medicine, working toward a statutory right to free, quality, public provisioned health care of all citizens. Second, comprehensive labour rights protections, for decent and secure work conditions, and social security, to all workers including women, home-based workers, circular migrants and care workers.

The government should never resort to large punishing lockdowns again; the focus instead should be on extensive testing, tracing and targeted isolations. To the extent that people are kept away from work, there should be statutory duties to pay all of them the equivalent of minimum wages. I would look at both an urban and rural employment guarantee, that is stepped up during emergencies. I would empty out prisons. Schools should be shut last and opened first. There is much else, but most of this is in the direction of a regime of universal social rights.

The pandemic not only revealed the catastrophic public costs of inequality but also witnessed a significant increase in the wealth of India’s billionaires, including Gautam Adani. How do you interpret this stark contrast between the worsening poverty experienced by a majority of the population and the exponential wealth accumulation of a few individuals?

Yes, the swelling of Gautam Adani’s wealth by ten times at a time when most in the country became poorer and the economy shrunk more alarmingly than ever since Independence, is a stark marker of much that is terribly wrong with both governance and India’s chosen economic model. Through even the greatest health emergency of a century, the government seemed to prioritise private profit over the public good. And it would spend huge public resources on projecting India’s covid management as among the best in the world, an achievement stemming directly from the supreme leader.

India has the most vulgar, indeed inhumane inequality, but it is important to observe that this swelling inequality is nurtured by an extraordinary cultural comfort with inequality, the indifference to suffering and injustice of the working poor among people of privilege. India is tearing apart by the politics of hate, but also by its galloping inequality. The neo-liberal growth model has fully grown into a vehicle for runaway crony capitalism, symbolised in the nexus of India’s richest men like Adani and Ambani with the highest rungs of political power. If this is to change, there is no pathway except to turn our backs of neo-liberalism and to tred instead the road of universal social rights in a welfare state.

The ruling establishment organised a spectacle of gratitude towards Prime Minister Narendra Modi, despite the unconscionable mistakes that led to avoidable deaths. How do you analyse this and the subsequent efforts to suppress questions and accountability for the failures? What impact does this obfuscation of the truth have on public trust, transparency, and the ability to learn from past mistakes?

The earlier government had tempered neo-liberalism with an initial infrastructure of some social rights – qualified rights to information, work, education and food. It is these that saved millions of Indians during the catastrophe of a lockdown without relief, it was because of these that India did not plunge into famine-like conditions when the country locked down without relief spending.

But under Modi — as my friend political scientist Neera Chandhoke puts so well — citizens are being transformed into subjects. Citizens are no longer rights-holders, they are beneficiaries of discretionary government largesse. Social goods like subsidised food, gas cylinders, social housing — and even vaccinations — have metamorphosed into elements of benevolence from the supreme leader.

The government is also unwilling to accept that it made any mistakes. Deaths are minimised, and government declares in Parliament, in the courts and in its public pronouncements outside that the government’s handling of the pandemic was exemplary, an example to the world; that there was no shortage of oxygen or hospital beds; that walking migrants faced no hunger; and so on. In such conditions of breathtaking public denials — actually bare-faced lying by our leadership — this obliterates even the possibility of learning from mistakes and instituting reforms for the future.

In the face of collective amnesia surrounding past tragedies, how can society cultivate a culture of remembrance that acknowledges the suffering and failures of the past while simultaneously fostering resilience and forward-thinking? What institutional mechanisms and societal frameworks can be put in place to hold governments accountable for their policy choices, ensuring that the needs and rights of marginalized communities are not disregarded during times of crisis?

We all seem seized by a collective amnesia of what was perhaps India’s largest humanitarian crisis after Partition, in which lakhs — arguably millions — of lives were lost because of a state that failed its people. Even in the state elections that followed the first and second waves, this was hardly ever a subject of political contestation. Mainstream media too has become almost entirely subservient to state power; therefore, it too did not raise difficult questions.

Also read: How Madurai writer-translator C Rajeswari became a master chronicler of MGR

It is, therefore, left to the citizen to resist this tsunami of forgetfulness. It is our highest public duty to remember — to grieve as well as to rage — about the criminal failures of a state that so profoundly failed its people, if we are to hold public officials accountable, and if we are to build back better in the future.

To what extent does the government’s complicity in perpetuating inequality and prejudice, especially after 2014, contribute to the indifference and apathy of the privileged classes towards the suffering of the working poor? How can we address this and build a sense of empathy and solidarity among different social classes?

The indifference of India’s privileged classes to the injustice and suffering of the working poor is not new. I speak of this at length in an earlier book that I titled Looking Away: Inequality, Prejudice and Indifference in New India. I argue there that India’s rich and middle classes are among the most uncaring in the world.

I search for reasons for this in their moral landscape, and find these in our inheritance of the caste system (which embodies the idea that the accident of a person’s birth legitimately determines her life chances); the British class system (which valorises old inherited wealth); and the neo-liberal idea that greed is good.

In the India of today, this moral landscape is further poisoned by the politics of hate against minorities. We are in the middle of what is no less than a civilizational crisis. There are no easy solutions. We have to build again, and this rebuilding has to begin with our collapsed moral centre.