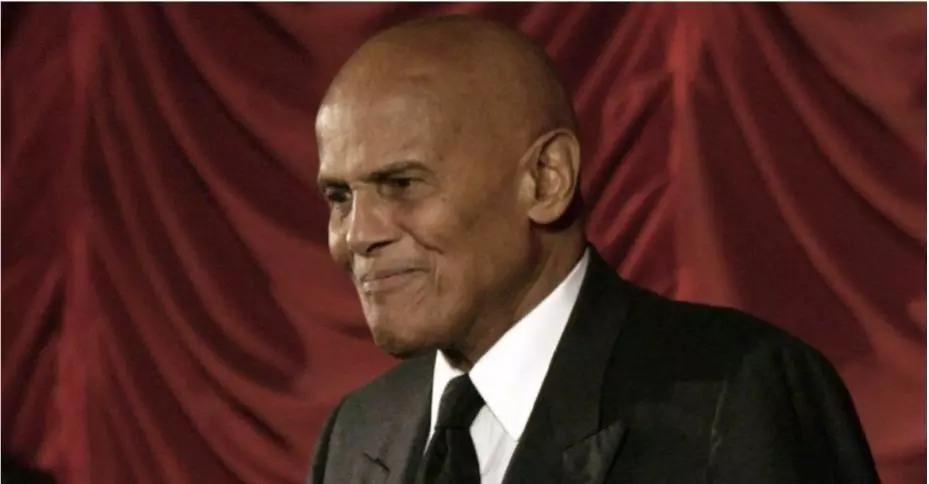

Harry Belafonte: How the singer-activist harvested his anger at being poor

The life of Harry Belafonte, the Jamaican-American singer, songwriter, actor, producer and activist, who passed away in New York on Tuesday (April 25), was not an easy one. He had occupied a lonely place, not just between West Indian and American culture, but between Black and White identities as well. He was angry at the poverty-scarred world of his childhood and the anger he felt about his circumstances only grew as he got older.

Belafonte, however, refused to let that anger consume him. Instead, he channelled it into a life-long mission to fight for civil rights and social justice —through his music, his activism, or his personal relationships. He used his fame and influence to raise awareness about the struggles of the marginalized and to fight against racism, poverty, and violence.

Throughout his life, Belafonte found guidance and inspiration from figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and the principles of nonviolence. He also sought to understand the complexities of his own anger, undergoing half a century of Freudian analysis to gain insight; it helped him. Long after he had immersed himself in the civil rights movement, he would still be trying to understand that anger, thinking of ways to make it melt away.

Also read: How International Booker Prize spotlights world’s under-represented languages

When he started his memoir, he could see the little boy he was ‘in all his complexities, angry and hurt, almost always alone.’ But it still eluded him why that boy had harnessed his anger to propel himself forward, to achieve greatness, and ultimately devote his life to tearing down racial barriers with determination. ‘Perhaps, in the end, where your anger comes from is less important than what you do with it,’ he writes early on in his autobiography, My Song: A Memoir of Art, Race & Defiance (2011), co-written with Michael Shnayerson. “I was born into poverty, grew up in poverty, and for a long time poverty was all I thought I’d know. It defined me; in the depths of my soul I think it defines me still. I felt not just angry but somewhat afraid, and vulnerable,” he writes.

Activism over art

Belafonte, who famously declared that he was “an activist who’d become an artist,” lived a life devoted to using art to advance civil rights and other important causes. Born into poverty and raised in New York City by a race-conscious mother who admired Pan-African movement leader Marcus Garvey and Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, Belafonte faced challenges early on in life, including the loss of sight in one eye as a child when he was fiddling with his white grandmother’s scissors. However, he also had influential supporters such as Eleanor Roosevelt and jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker, who backed him during his debut as a jazz singer at the Royal Roost in 1949.

Belafonte achieved early success in Las Vegas, on Broadway, and in Hollywood movies, but it was his adoption of a calypso style in the mid-1950s that propelled him to superstardom. By 1956, he was one of the most popular entertainers in America, with fans of all races connecting with his message of equality and civil rights.

Also read: What ho! With PG Wodehouse’s sensitivity makeover, we’ve gone too far in censoring classics

Despite his success, Belafonte never shied away from speaking truth to power. After meeting Martin Luther King Jr., Belafonte became an important player in the civil rights movement, using his resources and organizational skills to help advance the cause. In My Song, Belafonte vividly describes his work with such figures as John and Robert Kennedy, as well as his experiences during the March on Washington and the “We Are the World” recording session.

Belafonte’s art and activism often intersected: he used ‘We Are the World’ funds to fly to a remote corner of Ethiopia to deliver food supplies to starving residents. In his memoir, he revealed how his activism was the most important aspect of his life, not his music.

On song

In his memoir, Belafonte writes candidly about his personal and professional struggles, showing us the man behind the legend. He never lost sight of his moral purpose or creative vision, and he remained optimistic about the future until the end.

Growing up amid the gloom of the Great Depression, he had developed a passion for music at a young age and began performing in clubs and cafes around New York City, despite many challenges, including racial discrimination and segregation.

At the age of 17, Belafonte dropped out of high school and joined the US Navy during World War II. After his service, he returned to New York and continued to pursue his music career, which began in a club where he worked as a dishwasher. He soon became known for his unique style of Calypso music, a genre that originated in Trinidad and Tobago and combines African rhythms and Caribbean melodies.

Belafonte’s breakthrough came in 1956 with the release of his album Calypso, which included his signature song, Day-O (The Banana Boat Song). The song’s catchy melody and memorable chorus made it an instant hit, and it became a cultural phenomenon that launched the Calypso craze in the US.

Belafonte’s success in music opened the door to a career in television and film. He appeared in several movies, including Island in the Sun and Buck and the Preacher, and hosted his own television specials, which showcased his singing and acting talents. His albums sold in the millions, and he became a beloved figure in the world of television, winning an Emmy for Tonight with Belafonte.

The underground life

Belafonte’s parents, Millie and Harold, a cleaning lady and a ship’s cook, were illegal immigrants. The agents were forever on Millie’s trail because she had long since overstayed her visa. His parents were not legal citizens until they divorced and remarried US citizens — a process that took nearly two decades. This left the family in a constant state of flux. Till he turned 17, they lived an “underground life” as fugitives of sorts. They had very few family photos because they were too afraid of being identified.

Also read: Murakami’s latest novel has walls as metaphor for physical, emotional barriers

Belafonte’s mother taught him to never speak to strangers and, on weekends, she would leave him alone in the apartment while she worked domestic jobs with a friend. Despite being no more than four years old, he was warned never to answer the door, in fear of death. Belafonte was born as Harold George Bellanfanti, Jr. But Belafonte’s mother would change their family name and purchase forged papers when she felt that the authorities were closing in. Thus, Bellanfanti became Belanfonte, and then, after a few more variations, finally Belafonte. It’s no wonder that he felt angry about his poverty-stricken childhood and the difficult circumstances he faced.

A cultural icon

As one of the first Black leading men in Hollywood, along with his friend Sidney Poitier, who died in January last year, he paved the way for future generations of performers, proving that Black artists could not only be successful but also become cultural icons.

During his early years as a struggling actor in Harlem, Belafonte formed a close bond with Poitier, who shared his West Indian heritage and burning desire to escape grinding poverty. The two were born just eight days apart and became like brothers, with an intense competitive streak and occasional political and personal differences. Their bond was strengthened by their shared experiences of being black entertainers in a predominantly white industry. “Sidney and I were like brothers,” he writes.

My Song is an introspective look at Belafonte’s hardscrabble early life and his subsequent trysts with fame and affluence. Besides writing about his struggles, including his failed marriages and battles with depression, he also shares his insights into the people and events that shaped his life, including his friendships with King and the Kennedy brothers, and his experiences working with civil rights leaders and activists.

“I believe my time was a remarkable one,” Belafonte writes at some point in the book. “I am aware that we now live in a world overrun by cruelty and destruction, and our earth disintegrates and our spirits numb, we lose moral purpose and creative vision. But still I must believe, as I always have, that our best times lie ahead, and that in the final analysis, along the way we shall be comforted by one another. That is my song.”