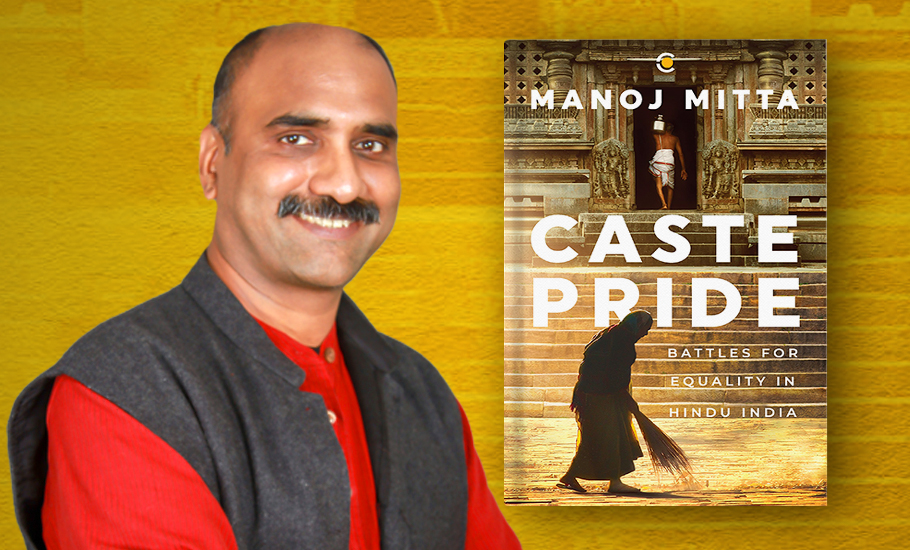

‘Caste Pride’ review: Manoj Mitta illuminates caste’s legal odyssey in post-Independent India

Caste represents the historical specificity of Indian society. There has been a fairly celebrated position among both scholars and political elite that caste will gradually lose its dominance and become a marker of less significance or no consequence with the acceleration of the process of modernity. This modernist position predicted that development, economic prosperity, expansion of literacy and urbanisation would lead to the decline of caste.

Different strands and variations of this position have existed from colonial times up to the present, advocated by eminent figures such as Jawaharlal Nehru, renowned sociologists of modern India like MN Srinivas, André Beteille, and DL Sheth, who have built their academic careers studying caste and village dynamics, and have pronounced the ‘decline’ and even ‘death’ of caste.

Caste as a hierarchical structure is not only the basis of division of labour, but also of labourers. While class differentiates society into haves and have-nots, the caste system places communities in a ritual order of higher and lower by birth and legitimizes it on the sanction of religious scriptural authority.

A ‘live’ reality

Caste has been dynamic and continuously responsive to economic, social, political, cultural, and even legal processes. However, these responses have not always been progressive, as one would hope, as regressive and even violent reactions have been significant aspects of the caste narrative.

Also read: Hospital review: Sanya Rushdi’s novel lays bare the fragile life of a woman grappling with psychosis

For instance, the colonial state could be seen as responsible for creating contradictory prospects. On one hand, it paved the way for the strengthening and consolidation of the dominant caste-based landed, business, and educated classes. On the other hand, it also opened up possibilities for anti-caste aspirations and mobilization.

Caste has been much studied, commented, and criticized by scholars, both Indian and foreign. This is understandably so because caste continues to be a ‘live’ reality. Its significance in the political sphere is most commented and analyzed for its being a conspicuous factor in electoral calculus, strategy and mobilization. Caste also figures prominently almost as an indispensable dimension of sociology of violence in India — caste atrocities being evidence of this.

A constitutional issue

Post-Independent India’s journey as a secular, democratic republic started with the promises of equality, liberty and justice. Their pronouncement in the Preamble of Indian Constitution imparts them a higher legal standing and opens up the legitimate possibility for social change. Caste as the principle basis of exploitation, discrimination, claims/ denials, exclusions becomes the major obstacle to the realisation of the constitutional idea of India.

The decisive shift in the caste-state relation — though partially attempted during the colonial period — marks a radical departure from the safeguard of varnashrama dharma being the duty (Kshatriya dharma) of the raja to ‘justice’, ‘liberty’, ‘equality’ and ‘dignity of the individual’ being the constitutional duty of the Indian state to its members who are no longer praja but citizen-subjects. This makes caste no longer a mere ‘social’ phenomenon, but a constitutional issue involving the state to eliminate caste-based injustice, inequalities and indignities.

As suggested above, caste has been under the sociological gaze for more than a century, resulting in countless theoretical and empirical-ethnographic studies. What has been conspicuously missing is the study of the legal life of caste. Even when an attempt is made, it is mostly in relation to reservations — Marc Galanter being the most well-known scholar in this respect. The recent work of Dag-Erik Berg, Dynamics of Caste and Law: Dalits, Oppression and Constitutional Democracy in India (2020), has been an important effort with a theoretical focus in this regard.

Also read: The arid, defiant world of International Booker-longlisted Tamil writer Perumal Murugan

Manoj Mitta’s Caste Pride: Battles for Equality in Hindu India (Context) is an important attempt at addressing this inadequacy. The merit of this book lies in its long durée focus. Beginning with the East India Company’s encounter with caste, moving through the British colonial interventions and abstentions to post-Independent India’s promises and challenges and performance, the book tries to map the legal trajectory of caste, as well as the veil caste casts on the resistance to law and reform.

The text is organized into five thematic sections, viz., Early Codes, Impure Majority, Access Barriers, Temple Entry and Impunity for Violence. Each section, covering a specific set of themes, collated information pertaining to the existing state of caste relations of domination, prohibitions and restrictions as well as social, political and legislative efforts for legal reforms, responses and reactions. It also highlights the obstinacy of caste, which is evident in its persistent nature, manifesting in various forms ranging from being recalcitrant to being nuanced — varying in magnitude and intensity.

It is a useful compendium of legal cases related to caste. The painstaking effort involved in the collection of factual information pertaining to these cases is evident from the dispersed sources cited. As Mitta claims, “a basic premise of this book” is to record “several milestones in combating caste [that] have gone unnoticed” and also to remember early stalwarts like Maneckji Dadabhoy, R Veerian, MC Rajah who fought for legislations against untouchability, for temple entry, opening up public places and providing public amenities to Dalits. The writer’s desire to restore them to their place in the history of struggle for caste emancipation is evident.

The anatomy of caste violence

Caste reform has two sides: Subaltern resistance is an important dimension of the anti-caste struggle. The picture of change would be incomplete without the reform efforts of savarna leaders like Madan Mohan Malaviya and Mahatma Gandhi despite their claim of being Sanatanists. Not only is their support to caste reforms and legislative initiatives important, but their active campaign among the upper castes to foster consent for these reforms holds even greater significance.

Leaders like Gandhi emphasised conciliation as the sure way of forging a sustainable change which coercion would not be able to achieve. Legal reform must go hand in hand with social reform to achieve the desired effect. Mitta’s sensitivity to this is noteworthy.

The last section documents a series of atrocities, ranging from significant to lesser-known incidents that captured national attention: Kilvenmani (1968), Belchhi (1977), Tsudur (1991), Bathani Tola (1996), and Kharlanji (2006), among others.

The anatomy of caste violence marks a shift in the post-Emergency period. The political economy of development clearly demonstrates two significant changes: One, the process of commercialization and marketization of the rural production, leading to the emergence of a market-savvy agrarian rich and their political consolidation in the regional parties and regimes. Two, increase in subaltern Dalit assertion and resistance to traditional forms of caste feudal exploitation and treatment, leading to an escalation in private caste violence, often with state connivance and even active support.

The judicial response to this, as Mitta notes, is disappointingly disproportionate to the scale and seriousness of the caste violence and crime. The judicial commissions constituted to investigate these cases, as evident from a recent survey conducted by MIDS (Chennai), have shown no discernible difference.

The Karamchedu massacre: An omission

This atrocious dynamic could be seen in its fullness in the infamous Karamchedu Dalit massacre in 1985, which curiously does not find a mention here. The Karamchedu massacre is illustrative of the changing physiognomy of caste violence. Karamchedu, a prominent village in Prakasham district in coastal Andhra, gained prominence due to a caste riot by the dominant Kammas on the Madigas, which led to the killing of six men and rape of three women, and several others wounded. This case is particularly instructive as it effectively dispels the misconception that caste violence is solely inherent in backward, semi-feudal societies.

Secondly, this village actively participated in communist-led anti-feudal struggles throughout history. Thirdly, the dominant caste Kammas, who supported the communist movement and were influenced by the rationalist atheist movement, were not typically associated with practicing untouchability or engaging in other forms of caste discrimination.

However, despite its apparent progressiveness, the village and its surrounding areas became the site of a violent caste riot, highlighting a new facet of caste dynamics. This incident illustrates that even when caste loses its significance as a ritual-based system of superiority, it can still perpetuate economic and political dominance. In this case, the Congress-supporting Madigas of Karamchedu became targets of the Kamma community’s attack due to their refusal to shift their political allegiance to the Kamma-led Telugu Desam Party.

Also read: First Tamil cli-fi novel gives glimpse of lives of global climate refugees

The Karamchedu massacre holds significant importance in the history of caste-law relations. The national-level debates that followed this incident played a pivotal role in catalyzing the enactment of the groundbreaking SC and ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.

Caste Pride, as its subtitle suggests, deals with the struggles for equality denied in Hindu religion, the dominant faith in India. This issue assumes importance and urgency as Hinduism and its caste system have further been activated and find support and legitimization in the Hindu rashtra project of the Hindutva regime.

The book is meticulous in its extensive documentation of various laws, significant legal cases, and the struggles fought in the context of caste. However, one area where it seems lacking is in its ability to draw broader conclusions or generalize the findings.

If the empirical side of the text were to be accompanied by corresponding theoretical reflection, it would have enhanced its value and relevance manifold. Caste Pride, in addition to being an important source of information, would serve as a valuable reference for future researchers seeking to explore and delve deeper into the complexities of caste relations.

Karli Srinivasulu, Senior Fellow, at ICSSR, New Delhi, retired as Professor from Department of Political Science, Osmania University, Hyderabad