A lyricist for all seasons: Adios, Yogesh

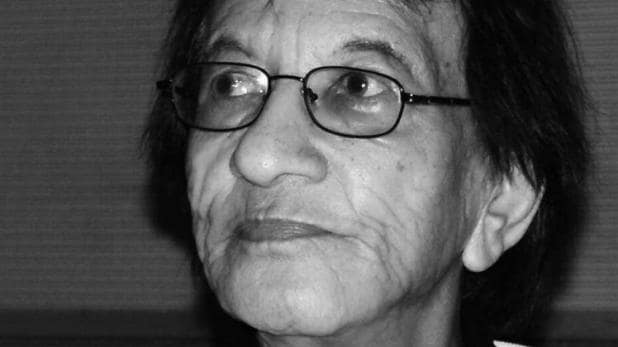

Yogesh Gaur, known by the mononym, Yogesh, who passed away at the age of 77 on May 29, was among a few lyricists, who through their words, could make listeners fall in love with commonplace things and their real lives.

Yogesh Gaur, known by the mononym, Yogesh, who passed away at the age of 77 on May 29, was among a few lyricists, who through their words, could make listeners fall in love with commonplace things and their real lives.

The rhythm of the foamy waves or the orange sun setting in a clear sky— are spectacles that one would witness on any given day. They are neither romantic nor dramatic, or even remotely alluring like the dewy moon. However, it was Yogesh, known for his paeans to commonplace events and real emotions of people, who could elevate all that is routine and mundane.

Born in Lucknow, Yogesh harboured a passion for poetry at a very young age. He began his career with the film Sakhi Robin in 1962. At a time, when lyricists and composers worked in partnerships, Yogesh had to wait longer to burst into the scene. He came under spotlight in the 70s– the revolutionary decade for Hindi cinema. Moving from the dreamy and romantic hills, in this decade, more number of movies were being set in the urban milieu. Filmmakers were willing to experiment with unconventional plots and a superstar called Rajesh Khanna was on a spree of hits.

It was at this time, editor-filmmaker Hrishikesh Mukherjee made Anand (1971), starring Rajesh Khanna opposite a four-film-old Amitabh Bachchan. For the story of a dying young man and his friendship with a brooding and idealist doctor, Mukherjee roped in music composer Salil Chowdhury and alongside, his favourite collaborator –screenplay writer and the prolific lyricist Gulzar– he brought on board Yogesh.

Mukherjee found magic in his lines—‘Kahin door jab din dhal jaaye, saanjh ki dulhan badan churaye, chhupke se aaye’–— when he heard them first. He coaxed the producer, for whom Yogesh had originally written the lyrics, to spare the song for his project. Today, it seems like those lines were penned specifically to capture Anand’s pain— who endures his sorrow with a smile—even with a turmoil in his mind that he hides from everyone. For the same film, Yogesh also penned an equally poignant ode to life ‘Zindagi kaisi hai paheli haaye, kabhi yeh hasaaye, kabhi yeh rulaaye’. Both numbers summarise the story of Anand—plumbing the different facets of his suffering.

With the songs, Yogesh, who was only 28 years old then, had arrived in Bombay and became a frequent collaborator with Mukherjee and Basu Chatterjee.

In the middle-of-the-road movies or the stories that struck a fine balance between art and commercial films, Yogesh, once noted that he wrote what he witnessed and lived, found his true calling. His words were wrought out of a vignette of relatable human emotions— sufferings, loving, losing and the disappointments in defeat. In simple and relatable Hindi, his songs breezed right into the hearts of listeners who were till then accustomed to ornate Urdu poetry.

RELATED NEWS: Irrfan Khan caught acting bug after watching his uncle perform in plays

Rajnigandha (1974) helmed by Chatterjee had just two songs and both were woven into the story. In ‘Rajnigandha phool tumhare, mehke yunhi Jeevan main’ (Lata Mangeshkar, Yogesh presented the metaphorical tuberoses (Rajnigandha) and its lingering fragrance comparing it to the blooming love in the protagonist’s heart, a woman.

The other number ‘Kai baar yunhi dekha hai, yeh jo mann ki seema rekha hai, mann todne lagta hai’ (Mukesh) is about her dilemma, after meeting an old flame and finding herself drawn towards him again. The deliberation he captures in the song is not just Deepa’s (played by Vidya Sinha), but also of most human beings who often find themselves amid such confrontations between their present and past.

Yet another memorable collaboration with Mukherjee was in Mili (1975), with a moving and soulful Badi suni suni hai (Kishore Kumar) — the last composition of SD Burman who was ailing during the recording of the album.

While Hindi cinema has fished out many memorable numbers in the rains of Bombay, ‘Rimjhim gire saawan sulag sulag jaaye mann’ for Mukherjee’s Manzil (1979) remains the most delightful of them all. The number with two different versions—male (Kishore Kumar) and female (Mangeshkar)–testifies for his wordsmithery— tailoring feminine and masculine emotions around the downpour.

In one, you see a kurta-pyjama clad Bachchan in all his simplicity singing at a wedding gathering, playing the harmonium, while in the other, a playful Moushami Chatterjee takes him through the roads of water-soaked Bombay. In the song, the man’s predicament of disclosing love in a gathering— ‘Mehfil main kaise keh de kisi se, dil bandh raha hai kisi ajnabi se’— poetically transitions to the innocent and effeminate joy of finding the routine rain suddenly romantic— ‘Pehle bhi yun toh barse the badal, pehle bhi yun toh bheega tha aanchal’.

RELATED NEWS: On board the Express called life: How trains played a role in Indian films

With some well-known movies like Chhoti Si Baat, Priyatama, Baaton Baaton Mein, Annadata, Dillagi and Apne Paraye, Yogesh’s run in the 70s continued to be successful. In the subsequent decades, he gradually moved into oblivion, even as he had his last project in 2017 with Angrezi Mein Kehte Hai. Times had changed, music and lyrics too had to.

In an interview in the last few years, Yogesh rued this fact, saying that today the only brief lyricists received was to come up with a ‘superhit number’. For someone, who shone in an era, when music and songs were integral to the plot, he could have never settled for the change.

Yogesh was not a top billed lyricist and he was never counted among the towering names of Sahir Ludhianvi, Shailendra, Hasrat Jaipuri and he was not likened with his contemporary like Gulzar. His ascent to success was gradual, moving from jhuggis to chawl and then a small flat in the ‘maximum city’. Probably, it was this contentment that gratified his thirst to find beauty in all things simple and real.