Oscar nominee 'Writing with Fire' turns lens on outliers in the system

Writing With Fire, the first Indian documentary to be nominated for the Oscars, failed to pick up the coveted trophy. Instead, the award went to Summer of Soul – a feature on the legendary 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, which celebrated African-American music and culture and fostered Black pride. Writing with Fire, which chronicled the rise of the all-women rural media network, Khabar Lahariya, had premiered and won the audience award in the World Cinema Documentary category at Sundance Film Festival in 2021.

Meanwhile, just a few days before the Oscar, Delhi-based filmmakers Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh found themselves caught up in an ugly controversy, as the Khabar Lahariya journalist team denounced the documentary. The team issued a statement claiming that the film portrayed the newspaper “inaccurately” by telling only their half-story and making it seem as if they were reporting on issues surrounding “one political party”. The team called the film an half-told tale and insinuated that they had a political-biased agenda.

The filmmakers, meanwhile, issued a statement saying that Khabar Lahariya has a rich legacy as a grassroots media organisation but a film must take a focus to tell a story of one aspect or another of the whole picture. “We respect that this may not be the film that they would have made about themselves, but we stand by this portrayal of Khabar Lahariya, which focuses on the range of the important work that they do — and their hopes, fears, vulnerabilities, and dreams,” said Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh, whose oeuvre include a docu on Dilli, which essentially is a visual essay on what the city is all about and Timbaktu, about a village in Andhra Pradesh which after a Green Revolution evolves itself into something completely organic.

The duo gave interviews to media outlets saying that they were “disappointed” by Khabar Lahariya’s reaction and it was an “acknowledgement of the fractured and complex times we are in”. (whatever that means!).

And, they made it quite clear that though they respect that this may not be the film that Khabar Lahariya would have made about themselves, but they stand by this portrayal of the news organisation. The film focuses on the range of the important work that they do — and their hopes, fears, vulnerabilities, and dreams,” said the directors in their statement.

“While their statement is deeply disappointing to us, we remain committed supporters of their mission, work, and onward journey,” they said.

Moreover, directors further said in their statement that they had shown the film to the Khabar Lahariya team who had loved it and had participated in their talk shows before its premiere at the Sundance Film festival. “The protagonists of the film expressed joy and support for the way the film represents their work and their lives. Soon after seeing the film, Khabar Lahariya’s Bureau Chief (Meera Devi) joined the filmmakers for a post-screening conversation at Sundance in January 2021,” said the statement.

Also read: ‘Our story more complex than one going to Oscars’: Khabar Lahariya slams documentary

What ‘Writing with Fire’ is about

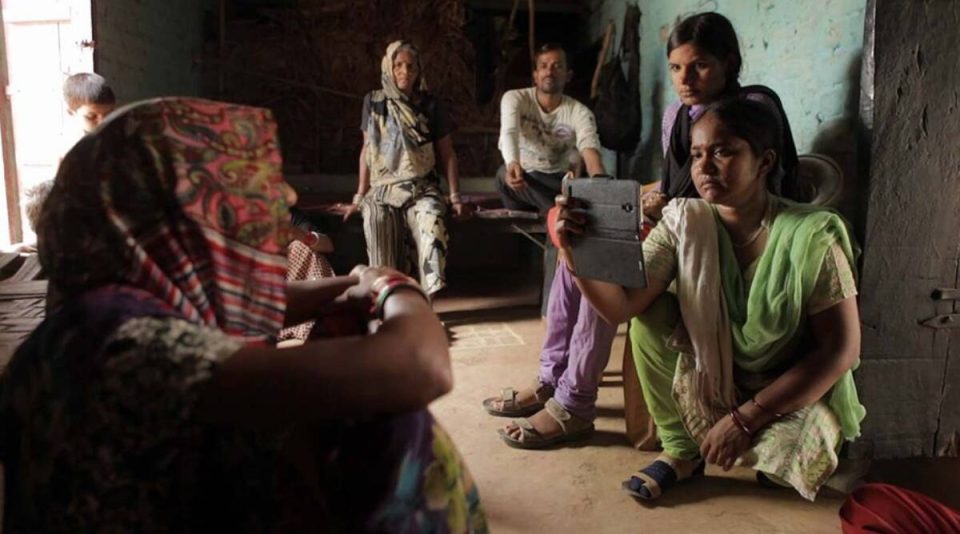

The film follows three spunky journalists — Meera Devi, Suneeta Prajapati, and Shyamkali Devi — of Khabar Lahariya newspaper in Uttar Pradesh’s Bundelkhand, covering a period of nearly four years from 2016 to 2019. Luckily for the filmmakers, the newspaper was transitioning to digital at that time and the film captures those moments when the reporters tussle with technology, having to navigate their smartphones to film news and send them across to their offices. The documentary too includes the gradual political transformations unfolding in the state of UP and the significant rise of the Hindutva forces.

The film starts with the chief reporter, a seasoned journalist Meera Devi, interviewing a Dalit woman, who is repeatedly gang-raped and the local police refuse to take any action against the rapists. It is a glimpse into how rural journalists work in tough conditions zealously tracking people who are willing to talk about the rising illegal mining mafia, on the lack of toilets and electricity and proper roads in villages.

Their stories get amplified on national media and the news outlet becomes the pride of the region. But the documentary also follows the reporters back into their homes and talks about their relationships with their husbands and fathers. In an interview with the director in one of the websites, Sushmit Ghosh said that there is a sweet relationship between Suneeta and her liberated, feminist daily wage labourer father who encourages his daughter to work and there is a scene featuring an affectionate banter between both of them at night before retiring for the night. But Ghosh said that they shot so much footage which had to be left out.

There is one scene in which Suneeta gets her passport to be able to travel to Sri Lanka for the first time to cover a conference. He is unable to comprehend her joy over acquiring a passport but he is willing to go along with it for her sake. That scene apparently did not make it to the documentary.

There are reportedly moments in the film that take you into these reporters’ homes and films their daily battle with their families. Meera’s husband, who doesn’t believe that their channel will last, considering that many big media houses are shutting down, criticises her for coming home late at midnight. But Meera is motivated by a dream – she believes that a Dalit woman in journalism is unheard off and wants to change that perception. She is personally driven to show when a Dalit woman has power, what she can do.

In Writing With Fire, the directors were very sure that it had to be an observational piece. They wanted to show how to give the viewer an experience of what it meant being a Dalit journalist in these parts of the country. Moreover, they wanted to capture the sheer physicality of the exercise of journalism in these parts. “It’s physically brutal. How do you exhaust the audience as well — the amount of walking, the travel. The counterbalance is the weird stoic nature of these women,” said the director.

The origins of Khabar Lahariya

Their roots lie in an initiative called Mahila Samakhya (MS), which began working with Dalit and Adivasi women to improve their reading skills. Eventually, MS also brought out Mahila Dakiya, a four-page broadsheet with local news and information. Published until 1995, it was the precursor to Khabar Lahariya’s newspaper, which soon became a reality when Nirantar, a gender non-profit organisation from Delhi stepped in to fulfil the journalistic aspirations of these feisty women.

Doffing your hat at grass-roots journalism

In a time, where journalists command huge salaries and enjoy the luxuries of the press clubs in different parts of the country, these women remind you of the journalist of yore – the one with a jhola (cotton bag) slung on his or her shoulder trekking miles on foot to get a story.

Writing with Fire is an inspiring story of an all-women rural media network, which is running for 14 years, and turned digital to keep up with the times. It is a deep dive into their reporting styles, navigating a male privileged landscape and balancing their homes and work at the same time. It is story needed to be told and it is unfortunate the filmmakers crossed some boundaries and shaped the narrative to focus only on their caste identities and on their reportage of the rising Hindutva forces as alleged by the Khabar Lahariya team. (this could also have been because of the changing political landscape in the region during the filming of the documentary).

In their statement, Khabar Lahariya has objected to these two elements in the documentary pointing out they have not been able to carry their caste identities on their sleeves with with bravado and humour as shown in the film. “We have had to be discreet, often fearful. And even if we have written and reported from our particular caste identities, we have upheld the right to protect our families’ privacy, especially our children’s, who will come into these battles in their own ways,” said the statement.

But the filmmakers in interviews have said that their focus was to tell stories built around models of hope, about people who have been outliers to the systems, who have created tectonic cultural shifts, and then created change. Truly, there are pockets in India, which still give hope that good work gets done, somehow.