Asteroid City and the artistry behind Wes Anderson’s quirky, whimsical cinematic universe

‘The secret, I don’t know … I guess you’ve just gotta find something you love to do and then … do it for the rest of your life,’ says Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman), the charismatic and eccentric protagonist of Wes Anderson’s 1998 oddball multi-generational love triangle Rushmore, his breakthrough film.

This serves as a guiding principle for Anderson’s own trajectory as a filmmaker, from his debut feature Bottle Rocket (1996) to his latest sci-fi Asteroid City, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival this year, and had a wider release on June 23.

The Texan-born filmmaker’s fleet of 11 orderly, scrupulously composed and idiosyncratic films have remained rooted rigidly to the terrain of formalism, marked by distinctive stylisation, where fact mingles with fable, and reality is enhanced by imagination.

A ferment of storytelling

Set in diverse landscapes — from downtown Dallas to Northern India to rural England to dystopian Japan — and revolving around different subjects — from oceanography to fascism to foxes to dogs — his films not just feel intimately connected (cut with the same cloth of creativity and collaboration), but are a self-contained universe unto themselves.

Also read: Wes Anderson-inspired reels: Whimsy, melancholy beneath the candy-floss world

A ferment of storytelling and world-building, Anderson’s films boast a visual vocabulary unmistakably his own: each frame is steeped in the made-to-measure whimsy, and the unique vision of the individualist auteur, who turned 45 this year. At once immersive and introspective, they evoke a potent sense of nostalgia, capturing the essence of bygone eras with meticulous attention to detail and a wistful longing for the past.

In his explorations of loss, unrequited love, and the bittersweet nature of human existence — laced with a melancholic undertone (yet another Anderson-esque touch) — he strikes a balance between sentimentality and poignant reflection.

A symbolic framework

Though Anderson is frequently associated with American auteurs like Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, Steven Soderbergh, and David Fincher, his cinematic sensibilities align more closely with the quirkier lot: Coen brothers, Sofia Coppola, Spike Jonze, Terrence Malick, and Anderson’s close friend and collaborator Noah Baumbach, who has explored the complex threads of life, love and relationship in films like Marriage Story (2019).

Like his last film, The French Dispatch (2021), which is structured like an anthology, with multiple interconnected stories unfolding within the offices of a fictional American magazine (his ode to New Yorker, which has remained a personal favourite since his school days), Asteroid City unravels within a symbolic framework. This time, it’s a play-within-a-TV-show.

The creation of the new play, Asteroid City, by Conrad Earp (Edward Norton) is the centrepiece of the film, set in the American Southwest of the 1950s. As a theatre troupe on the East Coast prepares for their production named after the desert town, we meet an ensemble of characters, portrayed by a stellar cast — Tom Hanks, Margot Robbie, Scarlett Johansson and Bryan Cranston et al — against the backdrop of a junior stargazer convention in Nevada, where they all converge.

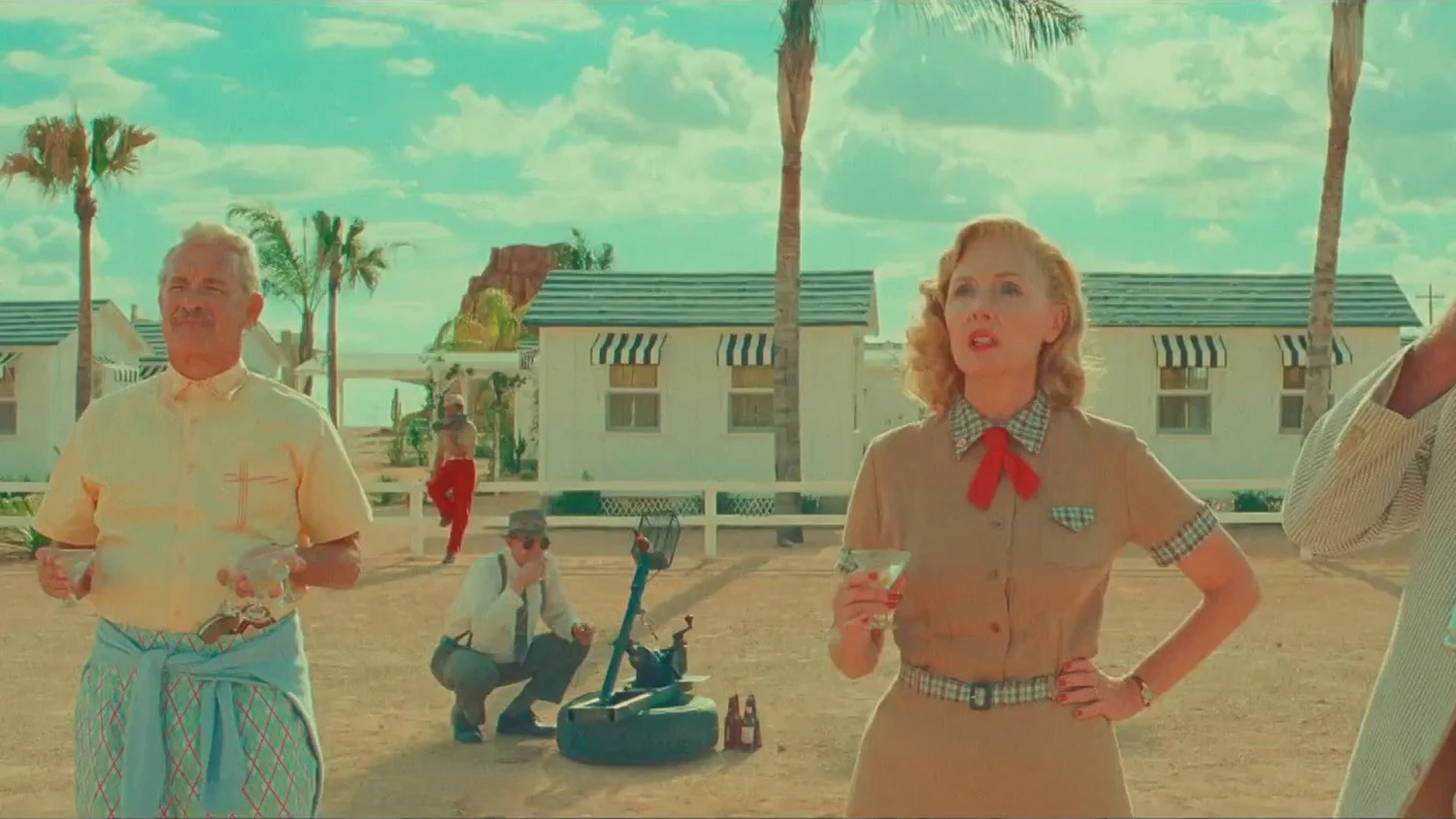

There is Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), a star who reminds us of the allure of yesteryear icons like Ava Gardner and Marilyn Monroe; she arrives in town with her gifted teenage daughter, Dinah Campbell (Grace Edwards), who is receiving an award at the astronomy convention.

Also read: Sneha Khanwalkar: Musician, traveller, storyteller — a story in three acts

Augie Steenbeck (played by Jason Schwartzman), a father grieving the loss of his wife, brings his four children to the town, where he breaks the news of their loss to them, leaving them grappling with their individual ways of coping — seeking answers about the afterlife.

The human connect

The story takes an unexpected turn during the ceremony to award the coveted $5000 prize for the best invention. An alien swoops down, taking away the asteroid decoration and vanishing into the night. In response, the government imposes a quarantine on the families to safeguard the secret of the encounter.

Asteroid City touches upon themes of grief and the afterlife, underlining the parallel creative impulses that drive both the pursuit of unravelling the mysteries of the universe and the desire to create meaningful works of art. The larger point that can be construed from the film is this: Amidst monumental scientific achievements, the most remarkable human achievement lies in the simple act of forging genuine human connections.

A meditation on the search for meaning, it exhorts us to ponder over existential questions, and reflect on life’s mysteries in our own ways. Like most of Anderson’s films, it’s preoccupied with the act of artistic creation itself. The film — no surprises here — is soaked in Anderson’s all-too-familiar artistic vision: his signature quirkiness, studiously designed retro-inspired costumes and sets, methodically conceived shots, nostalgic soundtrack, excessive focus on symmetry, and a vibrant colour palette.

Knots of family connections

The foundation stone of Anderson’s distinctive style and storytelling approach was laid with Bottle Rocket (1996), an indie crime-comedy film, which follows a trio of aspiring but inept criminals: Anthony (Luke Wilson), Dignan (Owen Wilson), and Bob (Robert Musgrave), as they embark on a series of small-scale heists and misadventures.

The film, which explores themes of friendship, loyalty, and the pursuit of unconventional dreams, has everything that came to constitute Anderson’s technique, including his trademark blend of deadpan humour, and endearing yet flawed characters — lovable underdogs.

The intricate knots of family connections, whether they are bound by blood, friendship, dysfunction, or deep-sea exploration, serve as the cornerstone of Anderson’s storytelling. These relationships provide the emotional and thematic foundation that runs through his films.

Anderson’s films spring from the well of his personal life and distinctive personality, evident in his corduroy suits, alphabetized bookshelves, and arty film references. They often reflect aspects of his own experiences, such as the inclusion of a literal film crew in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou or M. Gustave’s attempts to maintain civility amidst chaos in The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Also read: How artist Françoise Gilot, who has died at 101, fell in and out of love with Picasso

Tormented artists frequently feature in his films, showcasing Anderson’s soft spot for their struggles. Anderson’s approach to filmmaking goes beyond the surface level; he creates worlds that operate on a molecular level, with hidden depths and underlying currents beneath their visually enchanting exteriors. It is for this reason that they require multiple viewings to truly appreciate their richness and depth.

In his own handwriting

There are few directors in deft control of their process as Anderson. His scripts are in perfect sync with his directorial strategies and mood boards, which reveal colour schemes, fabric choices, and precisely planned camera movements. In his films, the clothing and adornments of each character, as well as the set design, play a crucial role in defining their identities.

The art direction and costume design, thus, become inseparable elements intertwined with plot twists and character backstories. “One of the things I like to dramatise, and what is sometimes funny, is someone coming unglued,” Anderson, who revels in unravelling characters, said once.

Similarly, Anderson takes great pleasure in constructing frames that exude his imprint. Every shot becomes an opportunity for him to infuse his visual style and aesthetic choices. “I have a way of filming things and staging them and designing sets. There were times when I thought I should change my approach, but in fact this is what I like to do. It’s sort of like my handwriting as a movie director. And somewhere along the way, I think I’ve made the decision: I’m going to write in my own handwriting,” Anderson said in an interview. It Asteroid City, he signs each frame with his cinematic penmanship.