- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Basavakalyan, a historic town in the Bidar district of Karnataka, witnessed a huge convention organised by the Jagatika Lingayat Mahasabha (JLM) in March, two months before the elections to the state legislative assembly. The idea of the JLM was to revive the demand for a separate religious status for the Lingayats, a community which constitutes more than 16 per cent of the population...

Basavakalyan, a historic town in the Bidar district of Karnataka, witnessed a huge convention organised by the Jagatika Lingayat Mahasabha (JLM) in March, two months before the elections to the state legislative assembly. The idea of the JLM was to revive the demand for a separate religious status for the Lingayats, a community which constitutes more than 16 per cent of the population of Karnataka.

Although the previous Congress government, led by Siddaramaiah, had forwarded a suggestion on the separate religious status of the Lingayat community to the Centre, it was rejected, mainly because the BJP-led government at the Centre wanted the Lingayats to always remain in the clutches of the Hindu tag. The decision of the Centre disturbed many in the community, which is known to be a strong support base of the BJP. The recent victory of the Congress in Karnataka, however, was a result of the huge turnaround of the Lingayats in the state assembly elections held on May 10.

The Lingayats today play a significant role in Karnataka’s political, cultural and social life. As the community’s demand for a separate religious status like the Sikhs and Jains gets stronger, we need to look at the origin of Lingayats and how relevant the 900-year-old belief system is today.

Basava is considered a representative of the whole community of poets-saints but there was equal respect for everyone among the sharanas.

Who are the Lingayats?

A journey in search of the origin of this group takes one to the Sharana community formed by a group of radical Vachanakaras during the 12th century AD. The community, which included people from cobblers to musicians to chieftains who wrote Vachana (short poetry or free verse poetry) in Kannada, came to be known as Lingayatas. About 12,000 such Vachanas, authored by more than a hundred spiritual-seekers and saints, which included 30 women, have been recovered so far.

What did these men and women express in their Vachanas? The Vachanakaras that stand out with their incisive commentary are Basava (1105–1167), a poet-statesman, and his contemporaries, Allama Prabhu and Akka Mahadevi, according to Shivanand Kanavi, adjunct faculty, NIAS, Bengaluru.

“What they advocated in words and deeds was spiritually liberating and attracted a large number of working people of all castes and even ‘untouchables’, artisans, farmers, traders, and some enlightened Brahmins. They called themselves as ‘Sharanas’. They followed equality and mutual respect and they never bothered about where one came from and who he was,” he said, while speaking as part of a lecture and discussion on ‘Lingayata’ organised by the Literary Arts and Heritage Forum of the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru recently.

The Vachanas were not written in canonical texts or sutras. They were written by ordinary people in Kannada, the language they spoke. There were boatmen, cobblers, folk singers, vendors and the list goes on. All of them freely expressed their thoughts and ideas through Vachanas. Basava is considered a representative of the whole community of poets-saints but there was equal respect for everyone among the sharanas. There was no leader or organisational hierarchy. The interesting aspect about the Sharanas is that the women Vachanakaras enjoyed the freedom like their male counterparts those days. The active participation of more than 30 women Vachanakaras shows the secular and unbiased nature of the belief system.

Kanavi said there are two major trends in the present-day Lingayat community. One is to go to the spiritual roots of the community in the radical teachings of 12th century Sharana Vachanakaras. The other trend in the community pays formal obeisance to Basava and other Sharanas but adopts various practices of older Shaivism, including temple worship. “The 12th century was a significant time for Vachanas. But then there was a deadlock for almost two centuries until some commentators introduced the radical form of poetry by writing commentaries about them. The introduction helped revive the Vachanas. And there were Vachanas written till the 18th century,” said Kanavi.

The Sharanas never believed in temple worship or rituals. Kanavi said the Sharanas lucidly expressed their views in the people’s language of the region, Kannada, on their spiritual pursuit and their devotion to their personal ‘God’ whom they primarily conceived as formless. They (the Sharanas) followed a very secular way of thinking and they criticised practices based on the Vedic and Agamic rituals and animal sacrifices. For the sharanas, everyone was equal and they were against social discrimination based on caste and profession. There was great diversity and individuality among them.

One can become a Sharana through initiation, not by birth. “The new community formed by Sharanas practised a form of personal worship and meditation using a small ‘Ishta Linga’, which they were to carry on their body so that they can worship it wherever they are without any need for temples. Thus the new community came to be known as Lingayat,” writes Shivanand Kanavi in the recently published book titled, The Indians: Histories of a Civilization.

“There was growing popularity and numbers in this new community whose membership was open and inclusive. This eventually led to royal patronage in some kingdoms like Vijayanagara. This was so particularly during the reign of Devaraya II (1422–46). Later, important royal dynasties became followers of Lingayatism,” he added.

The most significant fact about the Sharanas was that they opposed discrimination against women in the spiritual field and so on. “They broke the Brahmanical taboos regarding women as inferior and unfit for spiritual self-realisation because of natural biological functions of menstruation and childbirth. Vachanakaras not only ridiculed the Vedic Agamic rituals of Yajna, Homa, and Havana, animal sacrifice and elaborate temple worship, but they also took on all those Vedantins and Advaitins who merely spoke of the lofty ideas of everyone having the same ‘atma’ but blatantly practised caste and gender discrimination. Vachanakaras frequently called them "Vag-advaitins" (Advaita only in words),” said Kanavi.

According to a sect of Lingayats who follow the radical teachings of the 12th century Vachanakaras believe that Lingayatism is a separate religion like Sikhism and it should not be identified with Hinduism. The Lingayats bury their dead unlike the Hindus who cremate their mortal remains. Scholars, however, say the burial rituals are different from Islamic or Christian ones. MM Kalburgi, a renowned scholar of Vachana literature, had brought out two volumes comprising more than 20,000 Vachanas under his editorship before he was assassinated in 2015. He wanted to see Lingayatism as a separate region.

HS Shivaprakash, a Sahitya Akademi award-winning poet-playwright, who has translated many Vachanas of 12th century Sharanas, said the Vachanas have an independent soteriological approach different from Bhakti and mysticism. “There were many Bhakti movements developed in various parts of India. Poet-saint Andal’s ‘Thiruppavai’ is an example of complete surrender. The Bhakti movement encouraged the slave system but at the same time it proved to be a liberation. All spiritual quests in India consider the world as an illusion, or of suffering. What makes the Sharanas different from others is the fact that they transformed labour into a kind of spiritual practice, a portal of liberation,” said Shivaprakash.

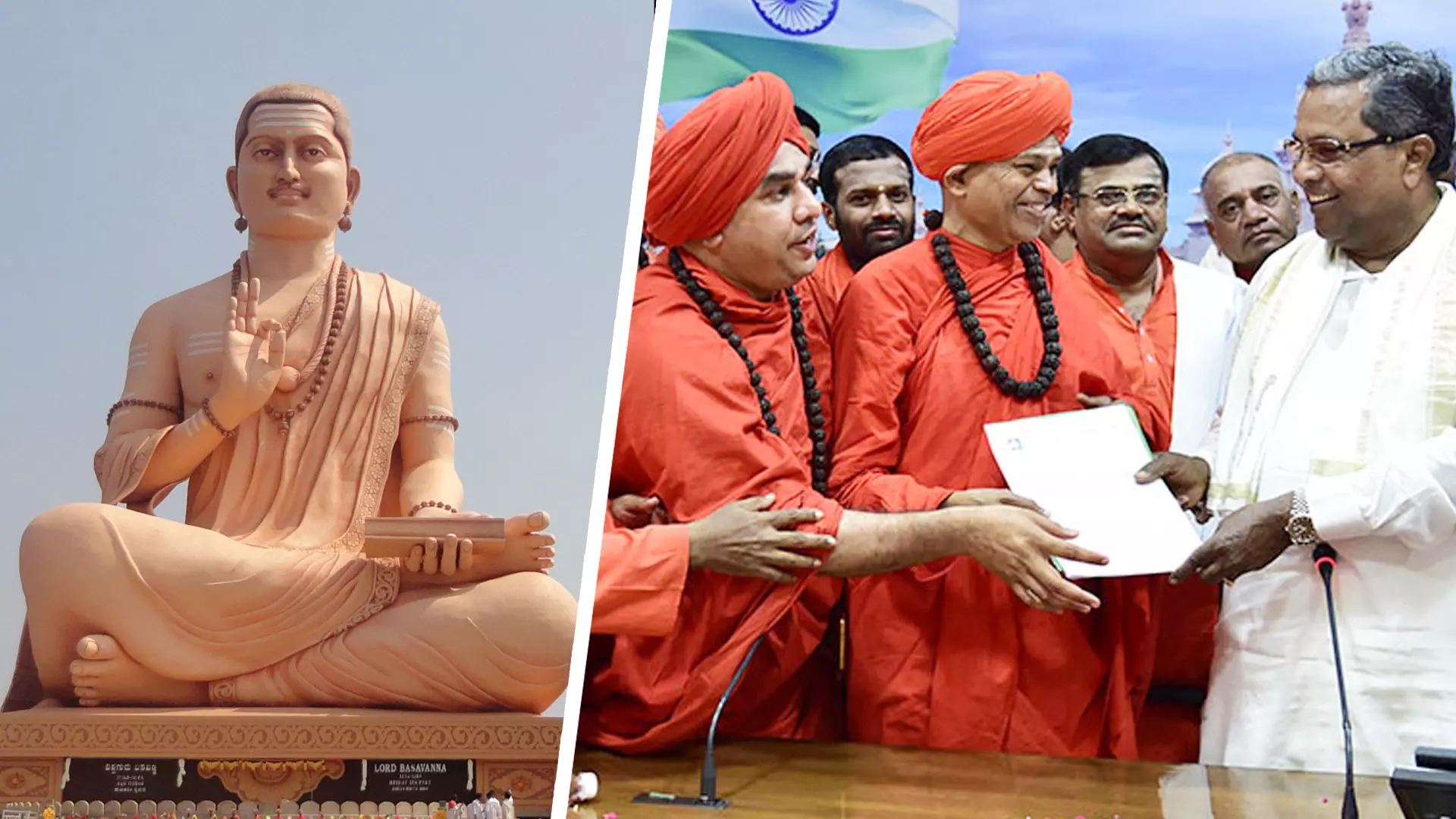

Lingayat pontiffs, demanding separate religion status, meeting Chief Minister Siddaramaiah. File Photo

“Labour is what upholds society. Without the plough and wheel, the world will come to a naught. I have never found this in any school of Indian spirituality. This is the most relevant spiritual philosophy for the world today but unfortunately only a little is written about it today,” he added.

The word ‘Lingayat’ was a later addition, as the 12th century Vachanakaras called themselves ‘Sharanas’. Today, there are hundreds of Lingayat mathas across Karnataka. The Lingayats, according to Kavavi, were able to get education during the time of the British due to the efforts of some influential people in the community. He said the ‘mathas’ (community institutions) played a major role when it came to providing education to the people in the community. “In the 20th century, many mathas made special efforts to provide free boarding and lodging for poor students in their Prasada Nilayas without discriminating on the basis of caste all over Karnataka and continue to do so,” he said. The initiative, however, helped.

Lakhs of poor students could get education in good schools and colleges. The community could produce many intellectuals and professionals in various fields, a reason why it plays a major role in Karnataka’s political and social life today.