- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Why India, the land of Salim Ali, should be worried about its disappearing birds

“Where have all the birds gone?” This seems to be the common refrain of the birders these days. They have been concerned over the disappearance of a wide spectrum of species of birds — sentinels of nature and the feathered custodians of our ecosystem — in recent years. According to the 2023 State of India’s Birds report, about 60 per cent of the 338 species of birds have...

“Where have all the birds gone?” This seems to be the common refrain of the birders these days. They have been concerned over the disappearance of a wide spectrum of species of birds — sentinels of nature and the feathered custodians of our ecosystem — in recent years. According to the 2023 State of India’s Birds report, about 60 per cent of the 338 species of birds have experienced decline in their numbers. The reasons are many, ranging from loss of habitat in the wake of increasing urbanisation, the steady shrinkage of prey base, the aftereffects of climate change, and the diseases they keep contracting.

According to veteran naturalist Ranjit Lal, author of over 35 books — fiction and non-fiction for both children and adults — several species of birds, including common warblers, are no longer spotted anywhere. He attributes their disappearance to factors such as construction activities and the widespread use of pesticides. “Many species of birds feed on caterpillars and insects, which are rich in protein. They are crucial for their survival, especially when it comes to feeding their chicks. However, there are hardly any insects to be found in urban areas.” The pervasive use of fertilizers and pesticides has led to the degradation of the soil, posing a threat to the entire ecosystem. As a consequence, the number of birds keeps dwindling.

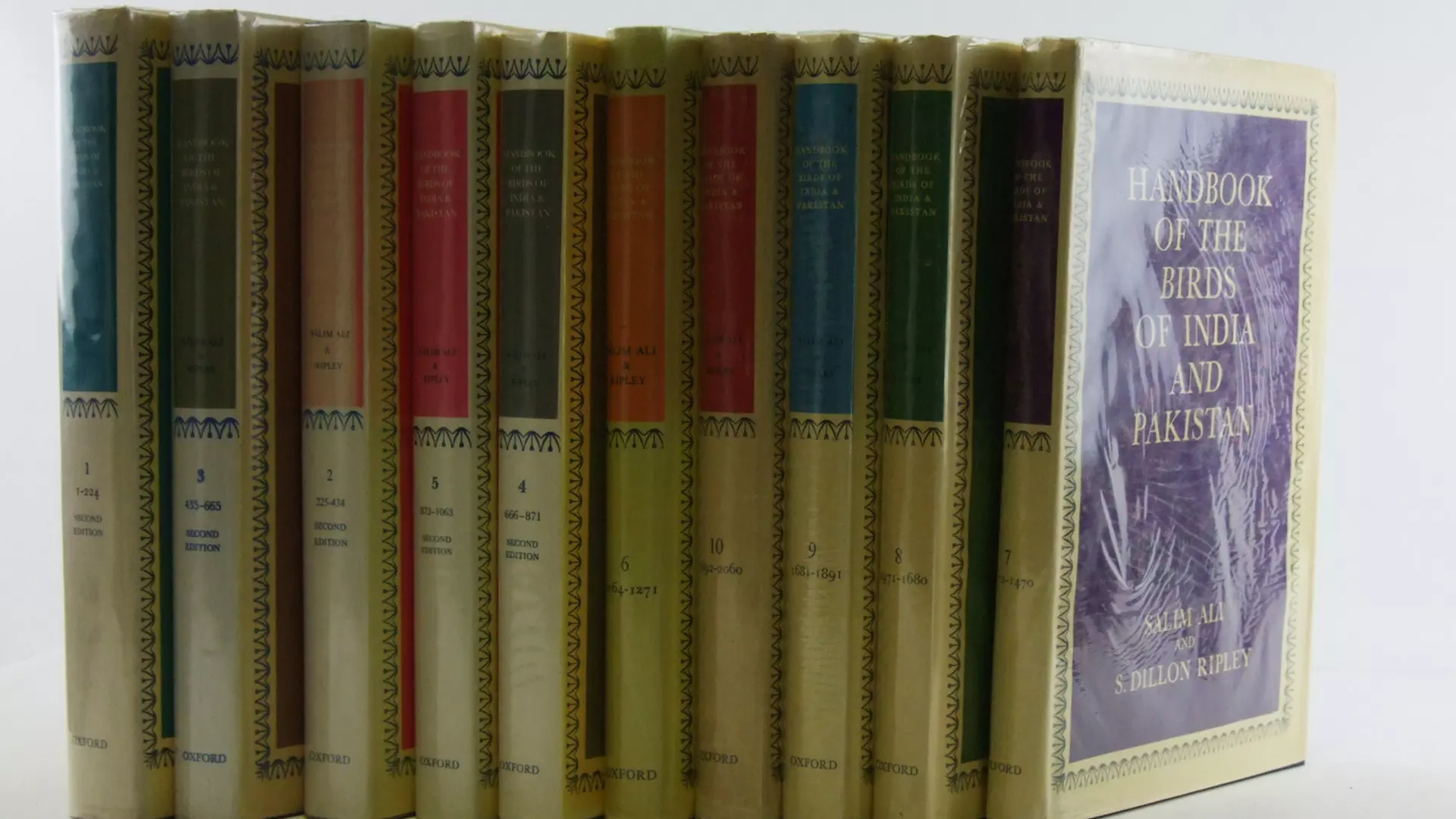

Salim Ali co-authored the colossal ten-volume Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan with S Dillon Ripley.

As we continue to focus on megafauna like lions, tigers and elephants, we continue to neglect birds. Lal underlines that in the race to develop, as we build highways, bridges and flyovers, we have little time to think about the birds. “Our children want to study Artificial Intelligence, but how many of them can say that they would want to study birds for the rest of their lives?” he wonders.

It’s tragic in the country of Salim Ali (1896-1987), the birdman of India, who made it possible for generations of birders after him to recognise/identify birds on the basis of their features and behaviours. The first Indian to conduct systematic bird surveys across the country, Ali also wrote several books that deepened Indians’ interest in ornithology, including the evergreen bestseller, The Book of Indian Birds, and the colossal ten-volume Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan, co-authored with S Dillon Ripley.

Ali had arrived at the discipline quite serendipitously. Born into a Sulaimani Bohra Muslim family in Bombay (he was the ninth and youngest child), he lost both his parents when he was an infant; his uncle Amiruddin Tyabji, who was the shikari (hunter) of the family, and his childless wife Hamida Begum raised him. Amiruddin had joined the Indian members of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) soon after it was founded in 1883. Growing up, Ali was fond of hunting sparrows in the tiny hamlet of Deonar, mainly for morsels of meat. During a hunting expedition in 1908, he stumbled upon a Yellowthroated Sparrow (Petronia xanthocollis). Still an adolescent, he could not recognise the bird, of course. It was done by the then BNHS Honorary Secretary, WS Millard, the head of Phipson & Co, Wine Merchants, upon a request from his uncle.

The meeting with Millard opened the horizon for Ali, he writes in The Fall of a Sparrow, his autobiography that he penned when he was in his late 80s. His curiosity about birds had really clicked, and it was at this point that his first ‘scientific’ interest in birds was born. In the book, he writes with great relish, and the skill of a natural raconteur, about his adventures in the outdoors, including his ‘birding’ expeditions to different regions, from Burma to Berlin, and Hyderabad to Dehradun. He also recounts his association with Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, Sarojini Naidu, S Dillon Ripley and EP Gee. When he had gone to meet Millard, it was with a bit of trepidation because in his mind, all Britishers, and especially those working for the Raj, were standoffish creatures with stiff upper lip. But, as he later discovered, Millard was anything but that. He gave Ali a few bird books from his small library to read: Edward Hamilton Aitken’s inimitable classics, Common Birds of Bombay and A Naturalist on the Prowl, which he read again and again over the six decades of his career with undiminished pleasure and admiration.

Salim Ali's The Book of Indian Birds is an evergreen bestseller.

Ali came of age at a time when ‘nature conservation’ was a phrase only rarely heard. At Khetwadi, a middle-class residential quarter of Bombay where he grew up, the spirited song of the Magpie-Robin would fill his ears day in and day out. Partridges and quails were abundant, and freely sold in the market. Birthday celebrations would entail the sacrifice of Grey Junglefowl or Red Spurfowl. Millard changed the course of his life by having Ali trained in skinning and preserving specimens and keeping proper notes about them at the BNHS. It was here that he met the Scotsman Norman Boyd Kinnear, who helped Ali gain further insight. Later, when Kinnear became the curator of the Special Providence Society and took over the reins of the British Museum, he put Ali under the training of two young assistants, SH Prater and PF Gomes. “They showed me over the entire bird collection and initiated me into the art of skinning, stuffing, preparing and labelling bird and mammal specimens for a study collection,” he writes.

Today, the birders have the luxury of travelling and shooting with 600mm bazooka lenses from inside their SUVs, equipped with GPS tracking. Ali had done all this by trawling through the length and breadth of the country on a bullock cart, armed with only binoculars. As a dilettante birder, he would devour books of natural history and adventure: George P Sanderson’s Thirteen Years among the Wild Beasts of India, Capt AIR Glasfurd’s Rifle and Romance in the Indian Jungle, Theodore Roosevelt’s African Game Trails, among others.

According to veteran naturalist Ranjit Lal, several species of birds, including common warblers, are no longer spotted anywhere.

It was a time when birdwatching was looked down upon as an amateurish, time-killing pastime of the idle rich; only morphology and taxonomy were regarded as ‘scientific’ ornithology. Ali’s interest always centred on the living bird in its natural environment. Later, when he wrote his own books, he made even the most prosaic and dry-as-dust nuggets of factual information interesting. If you read his prose, there will never be a dull moment. His felicity with the language makes his descriptions of bird-watching and surveying delightful.

As an ornithologist, Ali would take copious field notes on birds — observations of their occurrences and abundance, their habits, behaviour, associations, and other facets of their ecology and life history — in a methodical way, and indexed in a manner that made writing about them easier. “For the greater part of my bird-watching life, before the cassette type of mini tape-recorder and suchlike sophistications were born and became fashionable, the taking of detailed notes while actually working in the field was a comparatively slow and tiresome affair. A method that I had satisfactorily evolved for myself was to carry in my shirt pocket a small notebook and pencil and keep hastily jotting down on the spot. Besides making a list of the birds seen, I kept a running commentary of any interesting characteristic or unusual observation about them — of their general behaviour, calls and songs, food, nesting, social and interspecific activities or whatever, in a sort of hieroglyphic shorthand of my own,” he writes.

When he would return to his camp, he would decode these syncopated notes and transcribe into a special loose-leaf ledger, with each species under its own ‘account head’ in the style of commercial book-keeping, before the nuances were forgotten. Those were the years when the coloured printed books identifying the birds were rare. Ali made what was seen as a leisurely activity his passion and profession. As India sets for itself the target to become a $5 trillion economy, it would do well to also ensure that our rich avian heritage is protected at all costs, and the many contributions of Salim Ali are not forgotten or erased.