- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

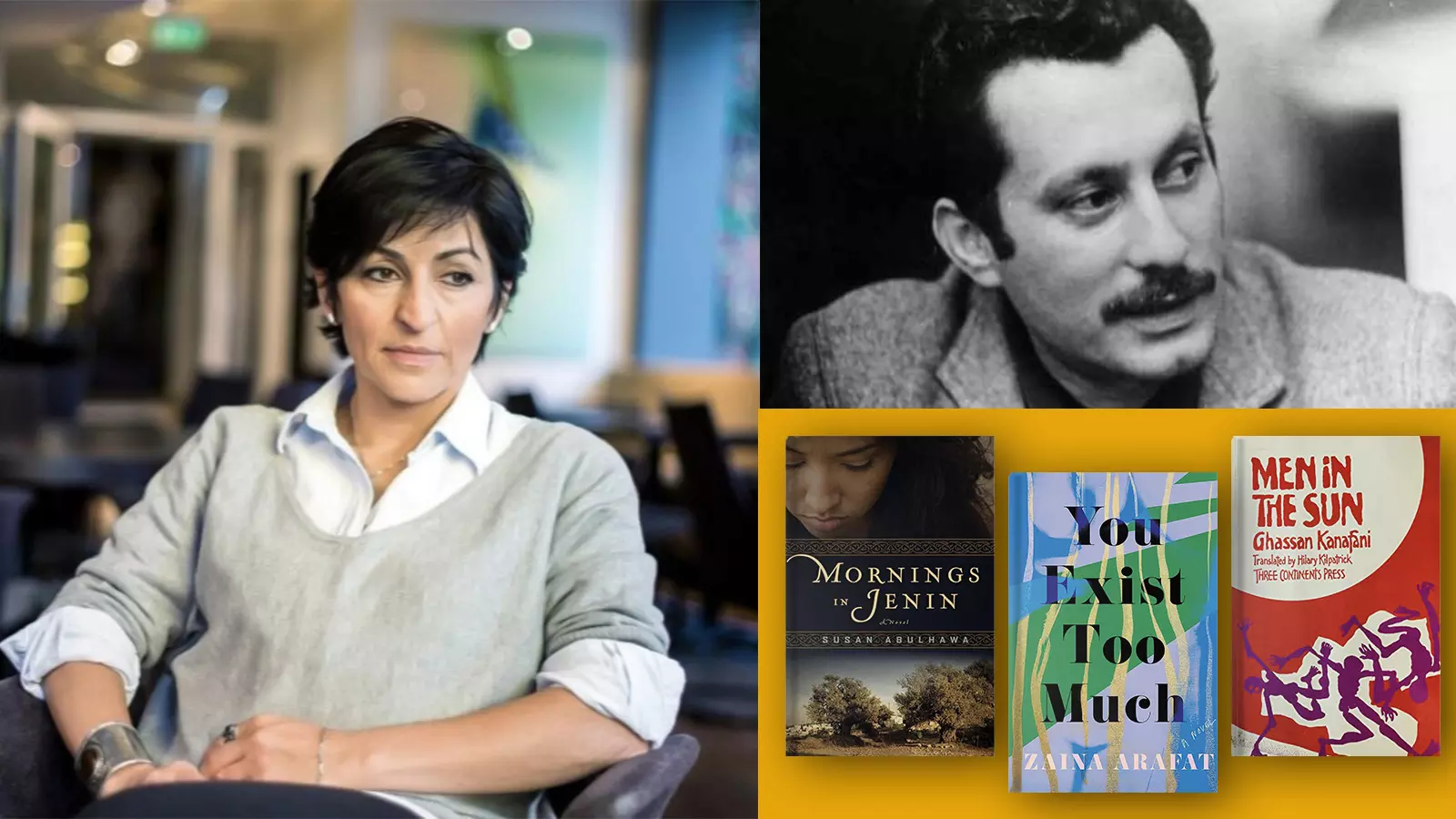

Palestinian novelist and activist Ghassan Kanafani, who was assassinated by Mossad in 1971, was the first to use the term adab al-muqawama (resistance literature) with regard to Palestinian writing. A prominent member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), he also wrote what is widely believed to be the first major work of Palestinian fiction, Men in the Sun (1962),...

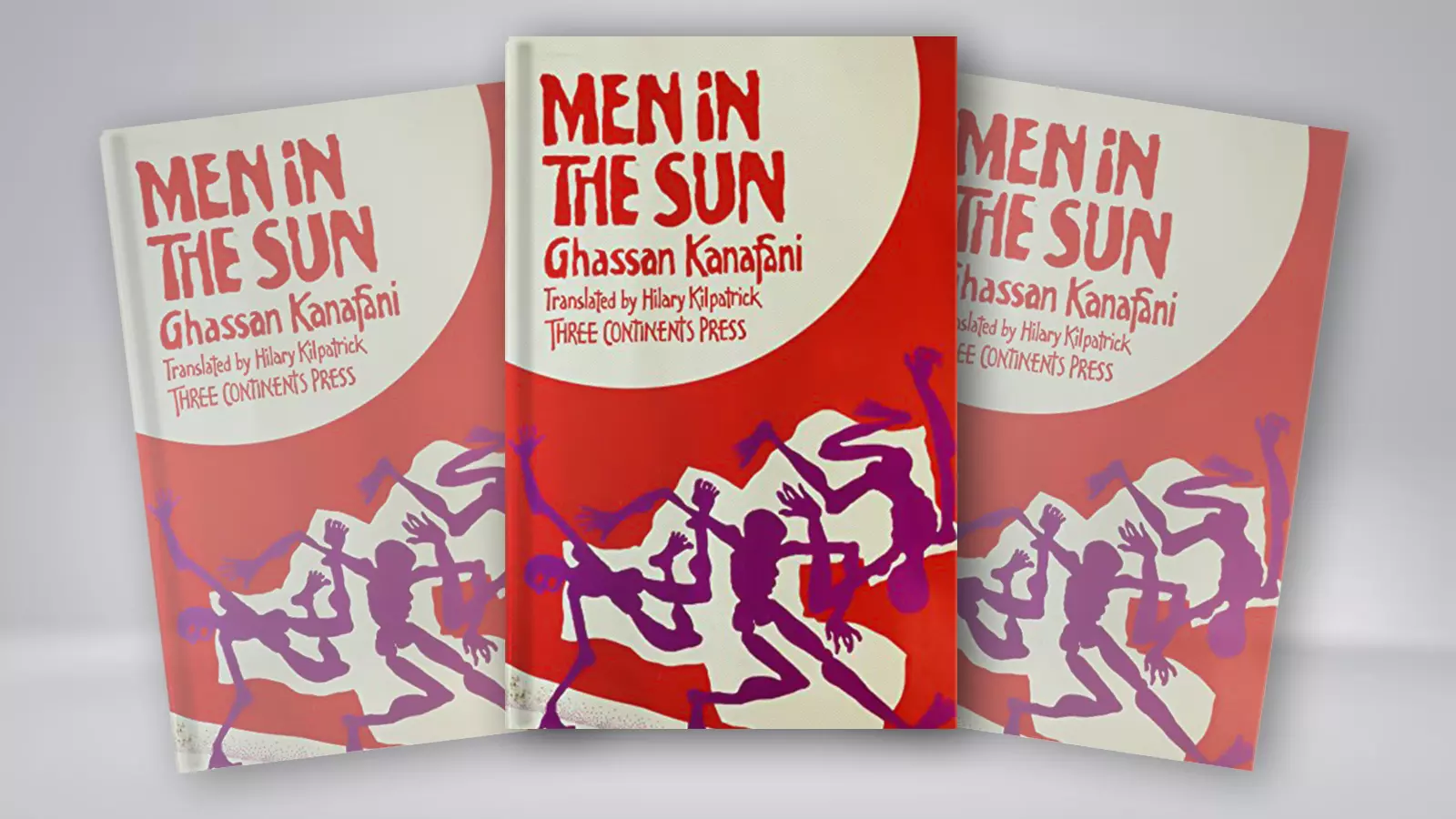

Palestinian novelist and activist Ghassan Kanafani, who was assassinated by Mossad in 1971, was the first to use the term adab al-muqawama (resistance literature) with regard to Palestinian writing. A prominent member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), he also wrote what is widely believed to be the first major work of Palestinian fiction, Men in the Sun (1962), a collection of short stories, which was translated from Arabic by Hilary Kilpatrick in 1999. He was only 36 when he was killed, along with his niece, Lamis, in the explosion of his booby-trapped car in front of his house in Beirut, the Lebanese capital. But he left behind, besides his widow and two children, an extensive body of work: five novels (two of them remained unfinished), five collections of short stories, two plays, and two studies of Palestinian literature.

In the memoir that Kanafani’s Danish wife, Annie, published after his death, she wrote: “His inspiration for writing and working unceasingly was the Palestinian-Arab struggle... He was one of those who fought sincerely for the development of the resistance movement from a nationalist Palestinian liberation movement into a pan-Arab revolutionary socialist movement of which the liberation of Palestine would be a vital component. He always stressed that the Palestine problem could not be solved in isolation from the Arab world’s whole social and political situation.”

Ghassan Kanafani, who was assassinated by Mossad in 1971, wrote what is widely believed to be the first major work of Palestinian fiction, Men in the Sun.

The stories in Men in the Sun explore the plight of Palestinian refugees, and the human cost of the Nakba, the forced expulsion of Palestinians in 1948. In the title story, we are introduced to Abu Qais, the first of the three Palestinian men who migrate to Kuwait. Qais, the oldest character, has vivid memories of Nakba, and often reminisces about the ten olive trees in Palestine. The longing for his lost homeland is evident in the very opening lines: “Abu Qais rested on the damp ground, and the earth began to throb under him with tired heartbeats, which trembled through the grains of sand and penetrated the cells of his body. Every time he threw himself down with his chest to the ground he sensed that throbbing, as though the heart of the earth had been pushing its difficult way towards the light from the utmost depths of hell, ever since the first time he had lain there….”

Men in the Sun, structured like a novella, is the story of three Palestinian men from different generations who seek the help from a clerk in Basra (Iraq) to get employed. Initially, they are set to be smuggled to Kuwait by a driver but they experience mistreatment and humiliation during the process. Disheartened by the ordeal, they opt to secure travel with a Palestinian lorry driver who had been surgically castrated during the 1948 war. The men are compelled to ride in the back of the truck, enduring a gruelling journey across the desert. At various checkpoints, they hide themselves inside an empty water tank, braving the sweltering mid-day heat while the driver manages the necessary paperwork to pass through. At the final checkpoint, tantalizingly close to their destination in Kuwait, the driver is delayed by bureaucrats who taunt him with rumours of his sexual escapades. After finally being permitted to proceed, the driver opens the tank to release the men, only to discover that they have perished during their arduous journey.

The stories in Men in the Sun explore the plight of Palestinian refugees, and the human cost of the Nakba, the forced expulsion of Palestinians in 1948.

Kanafani’s work dwells on the longing for home, and the resilience of a dispossessed people, uprooted from the places of their birth, and trying to make a home elsewhere, often paying with their lives in the quest for the same. In his 1969 novella, Returning to Haifa, a Palestinian couple travel to Haifa after the 1967 war, looking for their baby, whom they were forced to leave behind in the chaos of evacuation during the war of 1948. “His close involvement in the struggle for the recognition and restitution of Palestinian rights might lead us to expect that Kanafani’s novels and short stories would be no more than vehicles for the preaching of those principles, albeit in an indirect form. Part of his achievement, however, lies in the fact that he avoided this pitfall— for rather than transferring experience directly from reality to the printed page, he reworked it to give it a more profound, universal meaning,” Kilpatrick writes in the introduction to Men in the Sun.

The occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1967 — which triggered the second exodus of Palestinians — brought forth a new wave of literary expression, with authors like Sahar Khalifeh (82) and Emile Habiby (1922-1996) exploring its sheer impact on the Palestinian society. Khalifeh’s Wild Thorns, first published in Arabic in 1976 and translated into English in 1985, explores similar themes — of exile and longing — providing a window into social and personal interactions during the Israeli occupation. With its unvarnished depictions of daily life, the novel examines Palestinians’ quest for survival. Similarly, Habiby’s satirical novel, The Secret Life of Saeed the Pessoptimist (1974), bristling with humour and irony, is the story of a Palestinian man named Saeed, who writes a letter to an unidentified recipient, reminiscing about his life in Israel after he had to leave his home during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Later, he starts helping Israeli intelligence.

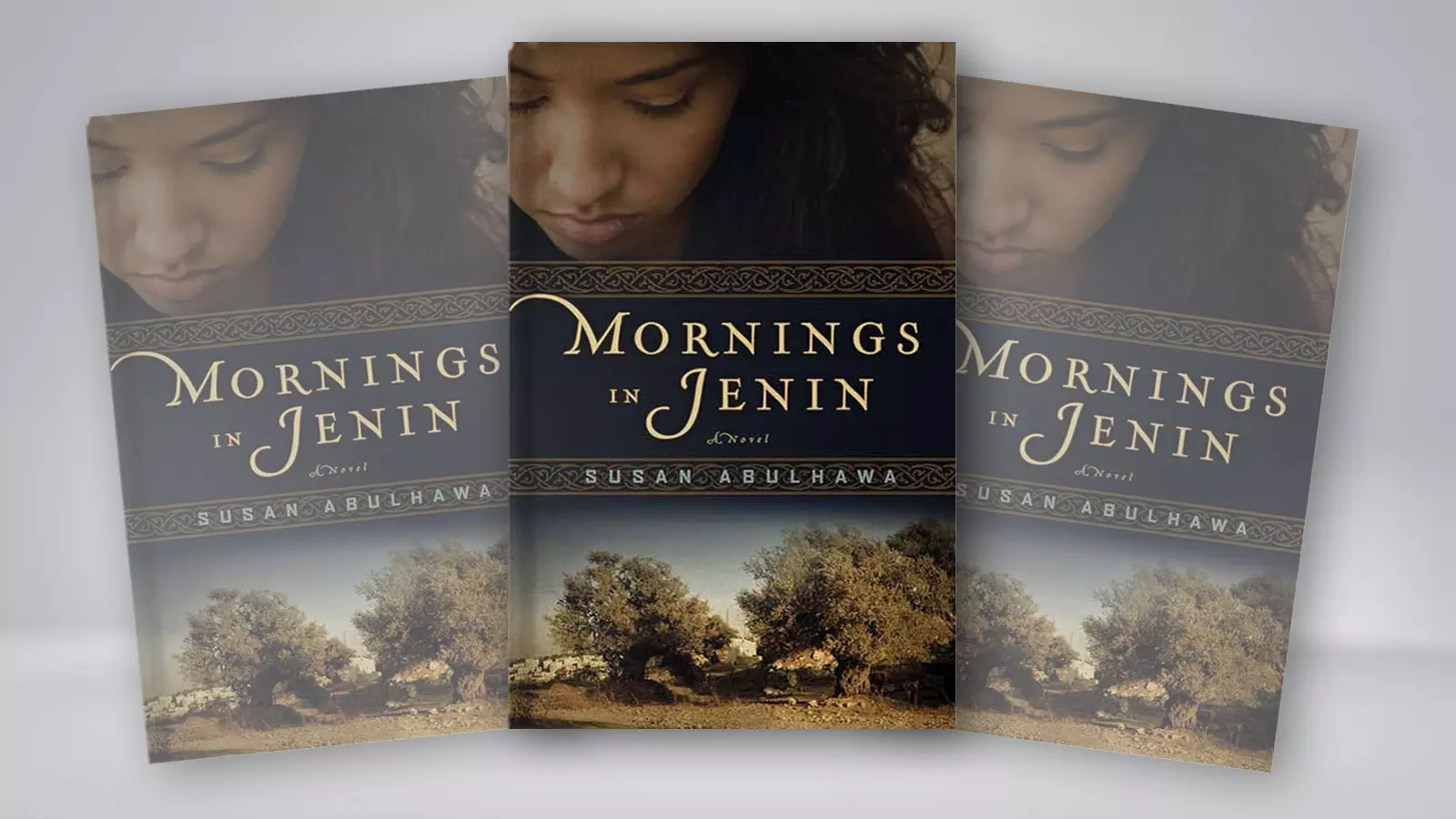

Pennsylvania-based Susan Abulhawa (53) has written three novels, and a collection of poetry on Palestinians.

Saeed and his wife Baqiyya have a son named Walaa. Unlike his father, Walaa joins a group fighting against Israel, and both he and his mother are killed by Israeli forces. Even though Saeed helps Israel, he ends up in prison multiple times, where the guards mistreat him.

Like fiction writers, Palestinian poets have also been instrumental in expressing the Palestinian experience. The poetry of Mahmoud Darwish, often referred to as the ‘national poet of Palestine’, is a striking example of the powerful connection between literature and identity. His poetry, lyrical and poignant, has a sense of longing that resonates with readers worldwide. Darwish has been hailed for using Palestine “as a metaphor for the loss of Eden, birth and resurrection, and the anguish of dispossession and exile”. Darwish’s work, such as The Olive Trees, reflect the deep-rooted relationship between the Palestinian people and their land.

Susan Abulhawa's Mornings in Jenin, originally published in the US in 2006 as The Scar of David — is the first mainstream novel in English to explore life in post-1948 Palestine.

The Palestinian literary canon is not confined to a single form; it traverses a wide range of genres, perspectives, and themes. It is a literature of protest, a literature of survival, and a literature of resilience. In recent years, a fresh crop of Palestinian writers in the diaspora have written about their people — those who left and those who stayed. Pennsylvania-based Susan Abulhawa (53) — writer as well as human/animal rights activist — is one of them. Founder of an NGO, Playgrounds for Palestine, she has written three novels, and a collection of poetry. Her novel, Mornings in Jenin, originally published in the US in 2006 as The Scar of David — the first mainstream novel in English to explore life in post-1948 Palestine, inspired by Kanafani’s Return to Haifa — is a multi-generational story about a Palestinian family, which is forcibly removed from the olive-farming village of Ein Hod by the newly-formed state.

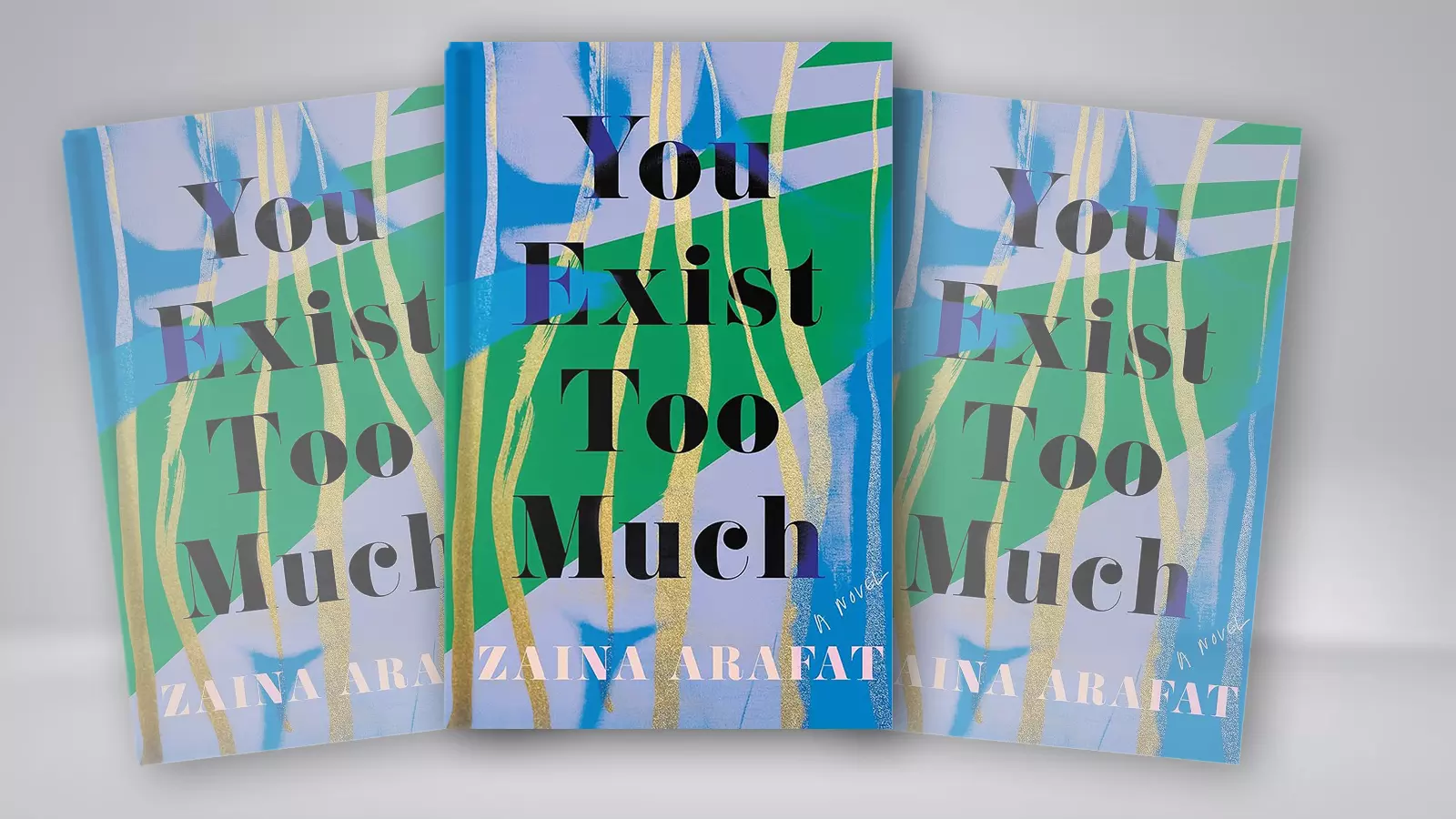

Similar strains of sorrow and displacement are found in the works of Hala Alyan (37), a Palestinian-American writer, poet, and clinical psychologist whose writing covers aspects of identity and the loss of land. Her debut novel, Salt Houses (2017), has a wide canvas: it follows the story of four generations of a fictional Palestinian middle-class family, the Yacoubs, and their journey through the Six Day War (1967), the First Intifada (1987), the Gulf War (1990), the Second Intifada (2000), 9/11 (2001), and the 2006 Lebanon War. In her debut novel, You Exist Too Much (2020), Zaina Arafat, a LGBTQ writer based in Brooklyn, tells the story of an unnamed young Palestinian-American woman — caught between cultural, religious, and sexual identities — through “a misguided and self-destructive quest for love”.

Zaina Arafat's debut novel, You Exist Too Much,tells the story of an unnamed young Palestinian-American woman — caught between cultural, religious, and sexual identities.

In her debut novel, A Woman is No Man (2019), Etaf Rum challenges the long-held code of silence within the tight-knit Palestinian American community of Brooklyn, a community in which she grew up, but later left. It revolves around two women who are subject to emotional and physical abuse: Isra, who hails from Palestine and is brought to Brooklyn for an arranged marriage with Adam, the owner of a deli in Manhattan; and Deya, their eldest daughter, who becomes the keeper of her mother’s story — which symbolises the experiences of countless Palestinian women across generations.

As Israel continues its offensive, some Palestinian writers are being targeted and cancelled. On October 20, Palestine-born novelist and essayist Adania Shibli, who divides her time between Berlin and Jerusalem, was due to be awarded the 2023 LiBeraturpreis, an annual prize given to women writers from Africa, Asia, Latin America or the Arab world.

The ceremony, which was scheduled to be held at the Frankfurt Book Fair (18-22 October) was cancelled; writers across the world have decried the “shutting down” of Palestinian voices. Shibli’s three novels depict the Palestinian experience of violence and injustice amid its scenic but troubled landscape. Her last novel, Minor Detail (2017), foregrounds the rape and murder of a young Bedouin woman by Israeli troops in 1949 and, decades later, the obsession of a Palestinian woman to investigate the stain of the crime; it shifts between past and present, third person and first person, the real and the imagined, and the borders of past- and present-day Palestine/Israel.

In an interview to this writer a few years ago, Shibli had said: “The major force that brings me to writing is language itself, and how it shapes our being on a linguistic level. This experience unfolds on multiple levels, erasure included, but it is not limited to erasure; the unfolding of the Palestinian condition on a linguistic level, but not limited to that condition. It’s about exploring whether our being can solely exist in Arabic language.”

She had added: “If we treat language as an entity that has its dynamics of collaboration rather than competition, it is only accepted that what is written is formed by what is not written. As for the form of any work, this often starts as an inescapable question related to language, to literature, to literary forms, which haunts me and haunts me until it gathers enough words and anecdotes, then it brings me to the moment where writing has to start.”

Adania Shibli's Minor Detail foregrounds the rape and murder of a young Bedouin woman by Israeli troops in 1949 and, decades later, the obsession of a Palestinian woman to investigate the stain of the crime.

Palestinian literature, which captures the essence of a people and their connection to the land, is also a repository of the historical injustices, the Palestinians’ struggle for self-determination, and, above all, storytelling as a means of catharsis. The horrifying events in the past weeks are bound to inspire many more writers to pen their narratives of pain.