- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Men in zenana to wonder water balloons: All that happens in the otherworlds of women sci-fi writers

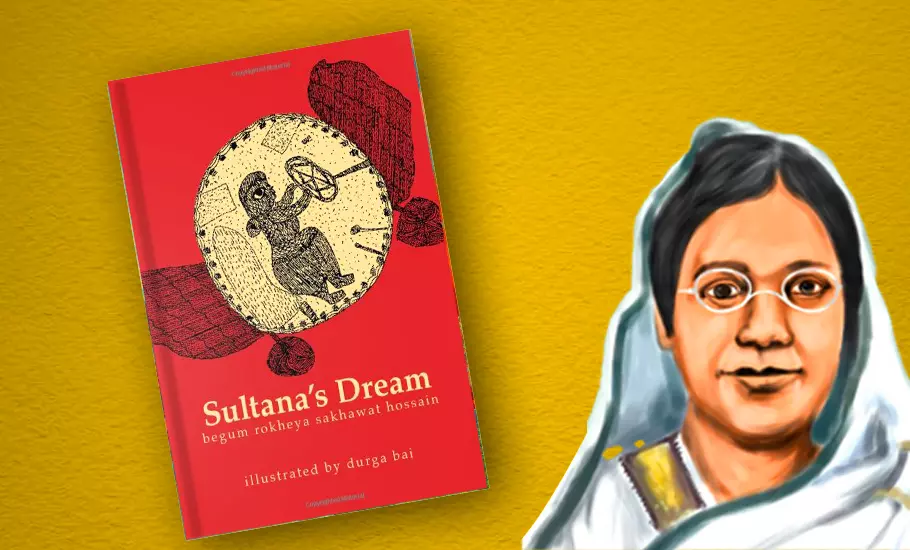

In the feminist utopia of Ladyland in Sultana’s Dream, a short story by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880-1932), widely considered to be the first work of science fiction in the subcontinent, men are shut indoors in the zenana (a place for women) — the tables have turned, and it’s referred to as mardana (a place for men) — while the fairer sex walk freely in the street, having vowed never...

In the feminist utopia of Ladyland in Sultana’s Dream, a short story by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880-1932), widely considered to be the first work of science fiction in the subcontinent, men are shut indoors in the zenana (a place for women) — the tables have turned, and it’s referred to as mardana (a place for men) — while the fairer sex walk freely in the street, having vowed never to allow themselves to be enslaved. It’s a land which the women have claimed after overpowering aggressive men in a battle through the power of their intellect — a land free from sin and harm, a land where virtue reigns supreme. Here, an epidemic is an alien thing, and no one dies in his youth. A land that resembles a well-manicured garden, where every plant is an ornament.

A wonder balloon, with pipes attached to it, is kept afloat above the cloud-land, and everyone is free to draw as much water as they please from the atmosphere. Ruled by a kind and compassionate Queen, who is fond of botany, its denizens “dive deep into the ocean of knowledge, and try to find out the precious gems that Nature has kept in store for us”. Women do not have time to quarrel because they never sit idle. And there is only religion — the one based on love and truth; a woman is considered religious if she is truthful.

Sultana's Dream creates a land which the women have claimed after overpowering aggressive men in a battle through the power of their intellect.

A dialogue — across time, space and cultures — between its narrator, Sultana, and Sister Sara, a stranger the former takes to be her friend, the story by the Bengali social reformer imagines a world beyond the social constraints of her time, when child marriage and purdah system were predominant. Rokeya, who was married at the age of 16, began her literary journey with the publication of her essay ‘Pipasha’ in the Calcutta-based magazine Navaprabha in 1902, but it was her ground-breaking short story — first published in 1905 in the Indian Ladies Magazine in Madras in 1905 — that made her a trailblazer of Indian science fiction.

However, it was only in 1973, 41 years after her death, that her work received critical attention. It was largely due to the publication of Rokeya Rachanabali (Complete Works of Rokeya), compiled by poet and critic Abdul Quadir (1906-1984), and published by the Bangla academy in Dhaka. Before Rokeya, it was another woman, English novelist Mary Shelley, who had written what is believed to the world’s first science fiction novel: Frankenstein (1818), the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist, who creates a sapient monster from pieces of the corpses.

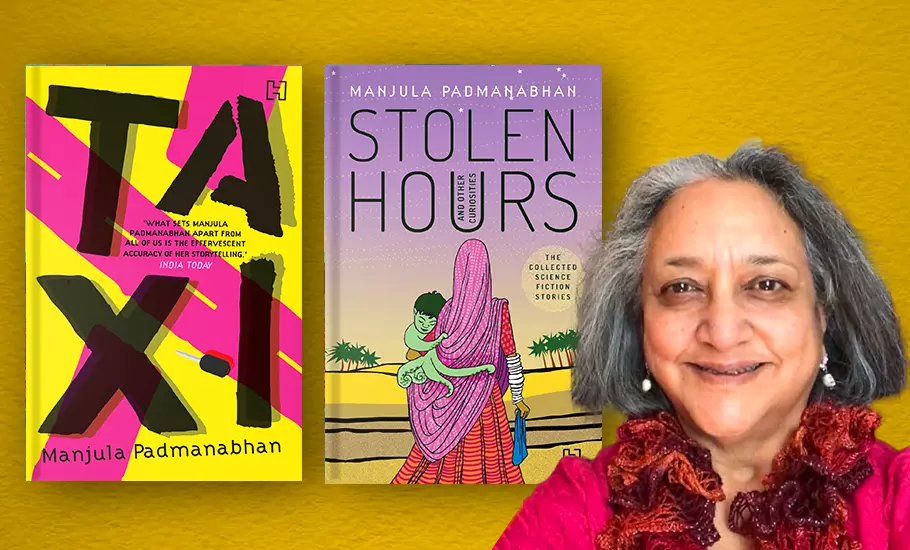

Fast forward to now, and we have scores of women writers who champion the genre of speculative fiction, referred to as sci-fi or SF, which includes both science fiction and fantasy — from Manjula Padmanabhan, Vandana Singh, Priya Sarukkai Chabria and Kalpana Swaminathan to SB Divya (pen name of Divya Srinivasan Breed), Lavanya Lakshminarayan, Tashan Mehta and many others. Their works are set in imaginary worlds — often a dystopia — where the fantastical gives us a glimpse of the shape of our collective future. Born in Delhi in a family of diplomats, Padmanabhan grew up in several countries around the world, including Pakistan, Sweden, and Thailand. When she returned to India as a teenager, she had become, by her own admission, “a naturalized outsider, and a foreigner to everywhere”.

Manjula Padmanabhan finds sci-fi writing a way of celebrating the ‘other-ing’ that she experienced as a young person.

“Writing SF is a way of celebrating the ‘other-ing’ that I experienced as a young person. Instead of travelling to other countries, I can explore alternate states of consciousness, timelines, body types, species, genders, dimensions,” writes Padmanabhan — also an artist, cartoonist and playwright — in the preface to Stolen Hours and Other Curiosities (Hachette India), which brings together all her SF works. Curiosity, she writes, is her guide but it also sometimes acts as her saboteur: “adventures in otherness can just as easily end with a snap of unfriendly jaws and an alien burp, as with a shower of stars and a flight of glittering hummingbirds.” She underlines: “The uncertainty is what makes SF fun or scary, irritating or entertaining.”

In her SF works, Padmanabhan takes us to a technologically advanced future that awaits modern nation-states like India. Using an eco-feminist perspective, sometimes she equates women to the nation-state. There is a strong undercurrent of social and environmental issues in her works. She draws our attention to what is alarming around us: illegal trade of organs and rape or female foeticide, for instance. Her novel, Escape, a post-modern dystopia, foresees a dark future for the nation if the curbs on individual liberty are not ameliorated. “The underlying message in her works is that reality can be fashioned out of dreams and that hope is not an empty fantasy. She conveys the idea that there is a lot of power in imagination; it has the ability to propose and bring about a change,” writes Urvashi Kuhad in Science Fiction and Indian Women Writers: Exploring Radical Potentials.

Born and raised in Delhi, Vandana Singh, a professor of physics who lives in the United States, writes both in English and Hindi. In her debut collection, The Woman Who Thought She Was a Planet and Other Stories (2008), she shows us how the SF genre gives us a “chance to find ourselves part of a larger whole; to step out of the claustrophobia of the exclusively human and discover joy, terror, wonder, and meaning in the greater universe.” In the title story, we meet a woman, who is inhabited by ‘small alien creatures’. In another story, a young college student stumbles upon a mysterious tetrahedron in the streets of Delhi. There is no way of knowing whether it is a spaceship or a secret weapon. The stories in Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories (2018) are equally fascinating. In a Kafkaesque story, an 11th century poet wakes up to find he has been transformed into an artificially intelligent companion on a starship.

As an SF writer, Vandana Singh realises the need to be comfortable with moving one's coordinate systems to see the world, the universe, from multiple gazes and perspectives.

As an SF writer, Singh realises the need to be comfortable with “moving our coordinate systems around so that we can see the world, the universe, from multiple gazes and perspectives”. She said in an interview: “SF allows us to question, to challenge, to bring into visibility our belief structures, our assumptions about ourselves and the world; for writers from post-colonial nations to imagine their own futures, their own alternatives, is a deeply revolutionary, freeing act.” She added: “We need new paradigms, new ways of relating to the non-human universe, if we are to survive the climate crisis. SF gives us the tools to write those other paradigms into being. By writing speculative fiction: We can reconnect with… the oldest works in the world-in which humans interacted with rocks, trees, stars, animals, demons and tree spirits,” underscoring that modern literature’s obsession with the exclusively human is a sign of a deep malaise, apart from being utterly boring and unrealistic.

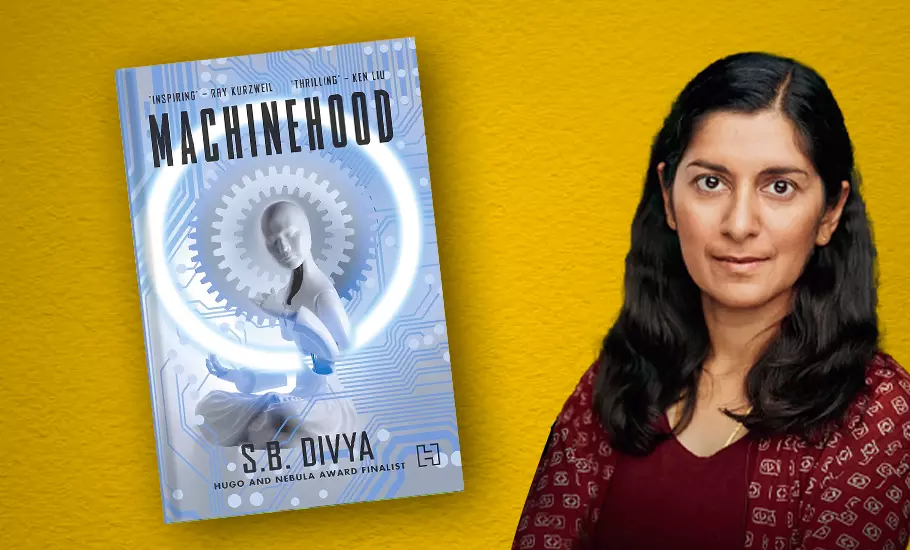

With her novels like Runtime (2016) and Machinehood (2021), SB Divya has become a huge favourite with SF readers in recent years. Through her exploration of the symbiotic relationship between technology and humanity, she bridged the gap between the present and the future. She makes us think about the ethical implications of technological advancements, and the impact of scientific progress on the human condition. In one of her stories in Contingency Plans For The Apocalypse And Other Possible Situations (2019), she delves into the “eternal conundrums of identity and love in speculative worlds.” We meet an ailing woman biologist, who researched her beloved microbiota by shutting herself off from the world and its deadly pollutants. Her latest novel, Meru, which released early this year, is centred on two women: Jayanthi, the adopted human child of Alloy parents (trans-human descendants of humans), and Vaha, her Alloy pilot, who form a bond while their time alone on Meru, an earthlike planet that is set to be colonized by the Alloys.

Through her exploration of the symbiotic relationship between technology and humanity, SB Divya has bridged the gap between the present and the future.

Both Padmanabhan and Vandana resist being labelled as women writers or a multi-cultural writer or a post-colonial writer because they want to discourage any attempt to put them in a box. The otherworlds they create in their works tell us a great deal about their unfettered imagination. In her 2015 novel Escape, the story of a girl named Meiji, a prisoner since her birth, who must escape the country of her birth to survive. Drawing on the declining sex ratio, the novel paints a horrifying portrait of a world which stands in stark contrast with the Ladyland of ‘Sultana’s Dream’, a world in which technology has overturned the natural means of production. In this Ladylessland ruled by men, everything is topsy-turvy, and women and Nature are considered to be the threats by the ruling class.

It is during her attempt to escape that Meiji realises who she really is, and how precious she is as the sole survivor of her species: “She comes to know what a ‘woman’ is. Even as she struggles to control the powerful forces within her body, she hears horrible tales of how women were killed by the Generals… the women were not allowed to survive because their minds could not be controlled. In one of the many manuals written by the Generals to guide the citizens, there is this quotation: ‘The drones are what the Vermin Tribe (women) should have been: servile, dumb and deaf.’ Meiji also comes to know that her own mother had publicly immolated herself in order to divert the attention of the Generals from little Meiji. She is angry with her mother for leaving her alone in a male world… She vows to keep on fighting for survival as a vital link in the precious chain of life.”