- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

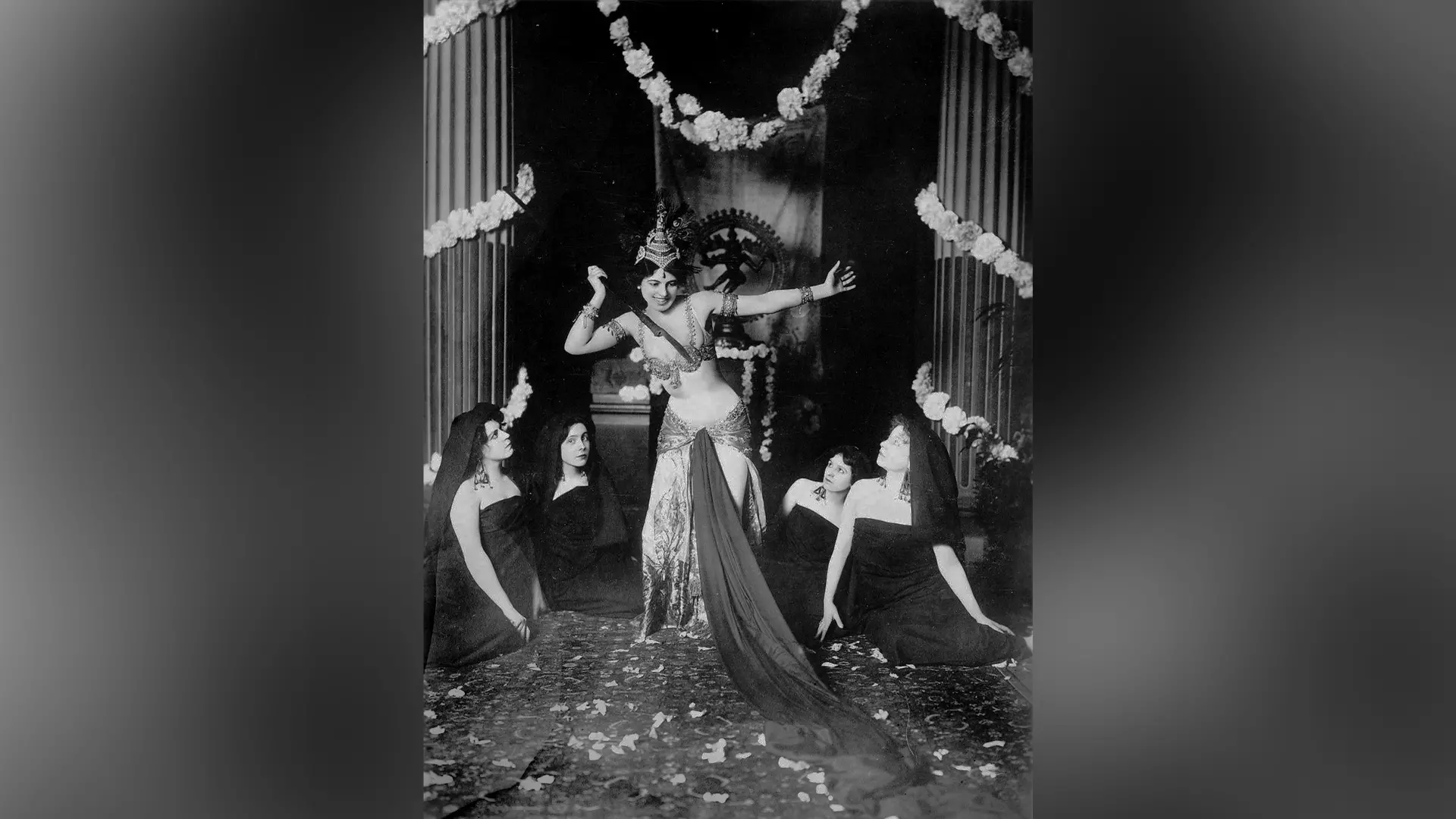

“An orchid in a field of dandelions.” That’s what one of her school friends had termed Margaretha Gertrude Zelle (1876-1917) before she came to be known as Mata Hari — an exotic dancer, a demi-monde, a seductive temptress, a femme fatale, and an international spy — whose life, steeped in allure and enigma, has been mythologised in the Western imagination; among those who have...

“An orchid in a field of dandelions.” That’s what one of her school friends had termed Margaretha Gertrude Zelle (1876-1917) before she came to be known as Mata Hari — an exotic dancer, a demi-monde, a seductive temptress, a femme fatale, and an international spy — whose life, steeped in allure and enigma, has been mythologised in the Western imagination; among those who have portrayed her on screen include Hollywood icons like Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo. In Leeuwarden, the Netherlands, where she was born, Margaretha’s friend, in all likelihood, may have chosen his metaphor unwittingly, but it came to summarise the life of the woman who was as exquisite, graceful and sensual as an orchid. But, alas, the flower also became a symbol of her vulnerability at a time when the ideal of male warrior hero had reached its zenith.

True, Mata Hari had her vices, too: the foremost was the fact that she loved men, many men. They became the damsel’s dandelions, her nemesis, who thrust her into the world of espionage, snuffing out her life barely two months after she turned 41. In the 106 years since she was summarily executed after a secret trial during World War 1, countless theories, myths and fantasies have proliferated around her. In the public imagination, she has been both venerated and desecrated, praised and pilloried. You will come across several versions of the legend of Mata Hari. But the most accurate account, if we are to believe her recent biographers, is the one that shows her as a woman who was more wronged than wrong. Thanks to a cache of trial archives as well as her personal and family letters, kept confidential by the French and published in 2017, we have more clarity now on who the real Mata Hari was.

“The most important thing to know about Margaretha Zelle is that she loved men. The most crucial thing to know about her is that she did not love truth,” writes American author-anthropologist Pat Shipman in Femme Fatale: Love, Lies, And The Unknown Life Of Mata Hari (2007), hinting that the spy may have fallen prey to the many ‘alternative truths’ or ‘lies’ she had invented; she found the truth ‘tedious’. The story of the mystery woman, who seduced scores of powerful men in Europe in the early 20th century and was subsequently maligned as a spy and a traitor, had seized Shipman in 2000. In July of that year, the archivists at the Institute of Anatomy Museum in Paris had found that the mummified head of Mata Hari, which had been kept in the museum’s collections since her execution in 1917, had vanished.

Mata Hari once told a friend that she never could dance well but people came to see her because she was the first who dared to show myself naked to the public.

A curator speculated that the seductress’ head might have been stolen by an admirer in the 1950s, the last time the collection had been shifted. “This seemed to me an extraordinary suggestion bordering on the fantastic. The thought of an ageing admirer stealing a woman’s head 30 years after her death was both ludicrous and macabre,” writes Shipman, who soon realised that when it came to Mata Hari, who had an insatiable thirst for adventure, opulence, and love, many unbelievable things were possible. Caught in a web of suspicion, when she was apprehended by the French authorities in 1917 (they accused her of being a German spy), she had hoped that she would scrape through, and reclaim the life in the high street that she had become accustomed to, even though it was marked by occasional penury.

But it was not to be. She was subjected to a trial that would seal her fate. Though truth was not her forte, she stated a truth about herself when she was in prison. The severe conditions of her imprisonment at the notorious Saint-Lazare and the catastrophic collapse of the world she had created had left her teetering on the edge of the abyss. In a letter she wrote to the man who was her captor, accuser, and interrogator, she explained:

“There is something which I wish you to take into consideration, it is that Mata Hari and Madame Zelle MacLeod are two completely different women. Today, because of the war, I am obliged to live under and to sign the name of Zelle, but this woman is unknown to the public. I consider myself to be Mata Hari. For 12 years, I have lived under this name. I am known in all the countries and I have connections everywhere. That which is permitted to Mata Hari — dancer — is certainly not permitted to Madame Zelle MacLeod. That which happens to Mata Hari, they are the events which do not happen to Madame Zelle. The people who address one do not address the other.”

It was a clear assertion of her self-understanding. By transforming herself into Mata Hari, she had fashioned the world to her liking, and cast herself in a mould that she loved to the hilt: the mould of a sex siren. With a great intuition of what would work, she developed a series of “sacred dances” that she ostensibly learned in the Dutch Indies. She had lived there for a few years after she married Rudolph MacLeod, an officer in the Dutch colonial army; twice her age, he was short-tempered and irritable, and the abusive marriage altered the course of Mata Hari’s life forever. He was quick to accuse her of infidelity. Ironically, as Shipman notes, the moral standards of European men in the Dutch East Indies were far from exemplary. Illicit relationships and out-of-wedlock affairs were common, often concealed behind a veneer of propriety.

Before their divorce was formalised in 1906, she had made one last-ditch effort to sort things out in 1902 by returning to Amsterdam to live with Nonnie, her daughter, and Rudolf; they had lost one daughter, Non, at a young age. The reunion was predictably short-lived and unhappy. Somewhere during this unsettled period, it was agreed that Rudolph would keep Non with him and Mata Hari would never see her again. Rudolph had longed for years to free his daughter of her mother’s influence, and Mata Hari was now desperate enough to agree. Her marriage and her motherhood were finished.

In 1903, when she came to Paris — she had no home, income, or prospects — she was determined to make a new life for herself. By hook or crook. Her body became her device to do so: men fell for her charm — hook, line, and sinker. Mata Hari, before she adopted the name which means ‘the rising sun’ in Malay, had left her mundane life as a married woman and a mother behind. She had lost her father, a rich merchant of haberdashery who had fallen on hard times, when she was 25. Her previous life had only made her miserable. Her new life gave her both fame, and infamy. It was in Paris that she began to create a mythology about herself. Her style was utterly novel; her ability to create a mood was strong; and her costumes were extremely revealing. As she explained later to friend and painter Piet van der Hem about this time in her life, “I never could dance well. People came to see me because I was the first who dared to show myself naked to the public.”

For her performances, she would get the magnificent sum of 10,000 francs, which had a buying power equivalent to about $42,000 in today’s currency. Typically, Mata Hari would spend more than her generous income. Once, she was sued by a Paris jeweller to whom she owed 12,000 francs — about $57,000 in today’s currency. The jeweller later agreed to allow her to keep her jewels if she paid him 2,000 francs a month. Debts were trifles to her. Success was the be-all and end-all. Her dance was a rage and whoever came to witness it, would be enchanted and ensnared.

“Mata Hari personifies all the poetry of India, its mysticism, its voluptuousness, its languor, its hypnotizing charm. To see Mata Hari in a rhythm and with attitudes that are poems of wild voluptuous grace is an unforgettable spectacle, a really paradise-like dream,” read a glowing review in The Journal. “One would need special words, new words to explain the tender and charming art of Mata Hari! Maybe one could simply say that this woman is rhythm, thus to indicate, as closely as possible, the poetry which emanates from this magnificently supple and beautiful body,” read another in The Press.

She became so popular that a series of postcards showing her dancing was issued in 1905-1906. Her costume resembled that of true Wayang dancers but was much more translucent — a move calculated to appeal to her audience. After her enormous theatrical success in operas like Le Roi de Lahore (The King of Lahore), the premiere of which had established Jules Massenet as the most popular composer of the day, Mata Hari was considered the most desirable woman in Paris, photographed at social events and fashionable spas in all her youthful and resplendent glory, leaving a trail of smitten admirers behind her wherever she went in Europe. When she performed in Vienna in 1906-1907, she was said to have caused heartburn to her dance rivals, Isadora Duncan and Maud Allan.

It is believed Mata Hari's mummified head was stolen from a French museum by one of her admirers.

Her scruples and joie de vivre came to an abrupt end as she kept falling in the cesspool of intrigue in the time conflict. Mata Hari, in many ways, became a victim of the upheavals of history, a collateral damage of the war: France was losing WWI and it desperately needed a scapegoat. During the trial, Mata Hari failed to convince the military tribunal of her ‘innocence’. In less than an hour, she was declared guilty. In a Paris courtroom, amid the whispers and gasps of onlookers, Mata Hari was convicted and sentenced to death. In the wee hours of October 15, 1917, she was shaken awake in her prison cell and given a pen, ink, paper and envelopes. According to an account by journalist Henry G. Wales, a correspondent for the International News Service, Mata Hari was allowed to write two letters.

Donning her black stockings, high heels and a velvet cloak lined at the bottom with fur, she scribbled the notes. “I am ready,” she said. Driven from her cell at the Saint-Lazare prison to an old fort on the outskirts of Paris, she stood face to face with her firing squad, 12 French officers, with rifles in hands, ready to fire. She was offered a white cloth to wear as a blindfold, but Mata Hari refused, saying: “Must I wear that?” The legend has it that she blew a kiss towards the French firing squad. It was her final act of defiance, and perhaps love, that would etch her name into history. No one came to claim her corpse; she had been living away from her family for nearly two decades.