- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Chennai’s manuscripts library holds secrets waiting to be decoded

The dreams of Colonel Colin Mackenzie, the first Surveyor-General of India, in 1821 in Calcutta (now Kolkata), outlived his life. His collections led to the creation of a manuscripts library in Madras (now Chennai). Mackenzie, also known as the ‘Manuscript Man’, collected a vast array of material, including Tamil literature, Sinhala medicine, Urdu poetry, Shilpa Shastra, the Rig Veda,...

The dreams of Colonel Colin Mackenzie, the first Surveyor-General of India, in 1821 in Calcutta (now Kolkata), outlived his life. His collections led to the creation of a manuscripts library in Madras (now Chennai). Mackenzie, also known as the ‘Manuscript Man’, collected a vast array of material, including Tamil literature, Sinhala medicine, Urdu poetry, Shilpa Shastra, the Rig Veda, and much more.

HH Wilson, an Orientalist who was assigned the task of cataloging Mackenzie's collections, sent large batches of manuscripts related to south India and some Southeast Asian regions to Madras in 1828.

Curator R Geethalakshmi showing a well-preserved manuscript in the library.

Mackenzie's priceless collection was initially housed at the Madras Presidency College Library. In 1869, the British established an exclusive library specifically to house his manuscripts. Today, these manuscripts are carefully preserved at the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library and Research (GOML), located in the Anna Centenary Library building in Chennai.

“Mackenzie had keen interest in the study of ancient mathematics and Oriental languages. He collected a large number of manuscripts, coins, inscriptions, maps etc, bearing on the literature, religion, history, manners and customs of the people not only from different parts of India but also from Ceylon and Java. On his appointment as Surveyor-General of India in 1818, Colonel Mackenzie took his valuable collections with him to Calcutta and went on adding to them till his death. This collection was bought by the East India Company from Mrs Mackenzie for 10,000 pounds the same year her husband died, and divided into three parts. While one part was retained in London, the other parts were sent to Calcutta and Madras,” she said.

She said later collections of other orientalists like Dr Leyden and Mr CP Brown were also added to the library in the later years.

With the historical insights, when we enter the library, the collection would surprise us. As visitors enter the library, they are greeted by an impressive gallery displaying manuscripts of all sizes and shapes. Contrary to common belief, manuscripts are not just long strips of palm leaves. The library’s collection includes manuscripts in various forms such as Rudraksha-shaped palm leaf manuscripts, a Shivling-shaped ‘Thiruvasagam’ manuscript, copper plate inscriptions, and even a leather-bound Bible written in Hebrew.

One of the most intriguing pieces in the library is a rare four-line manuscript, written on a palm leaf, which has been waiting to be decoded for over 100 years.

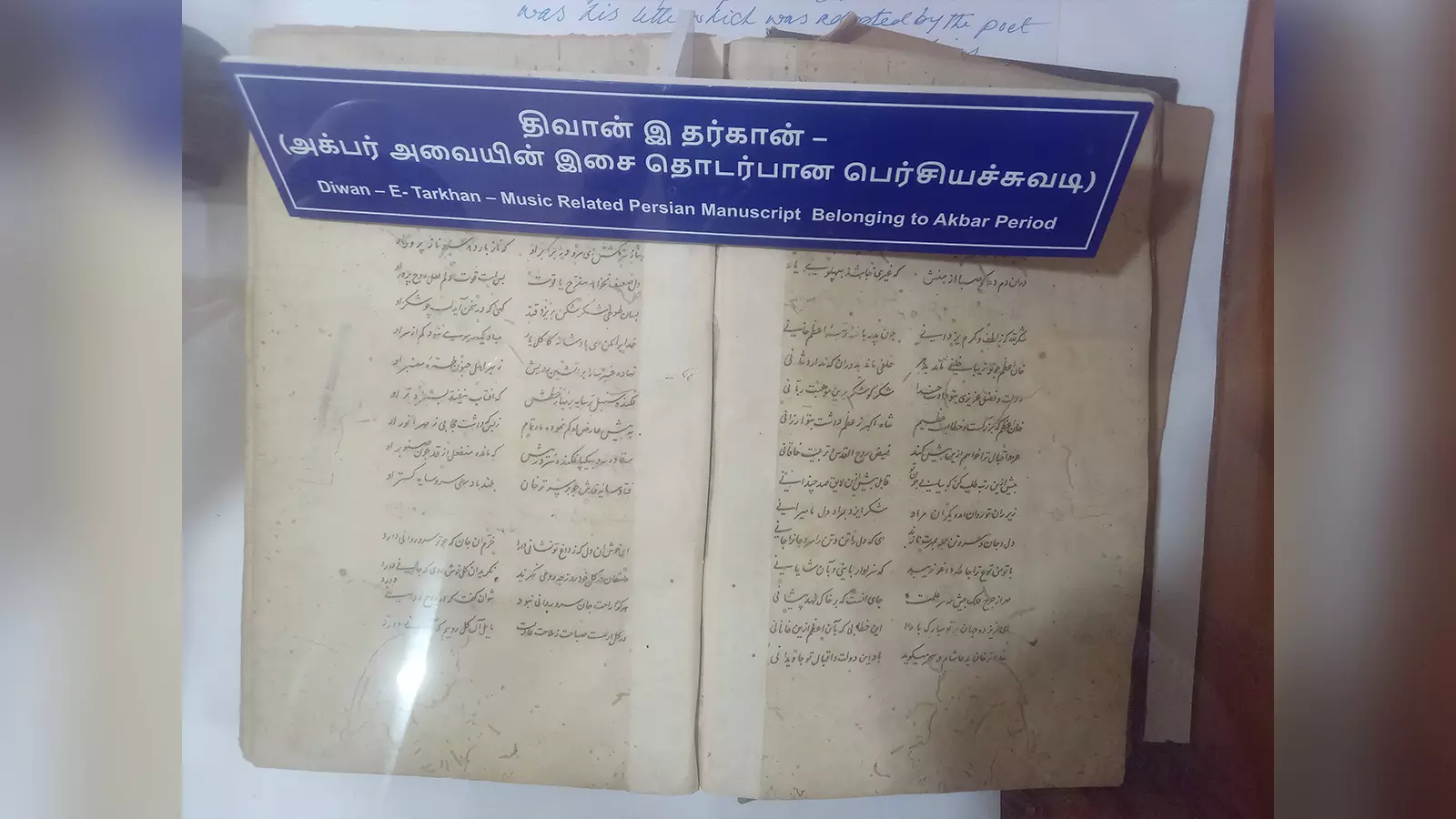

This paper manuscript has details on music instruments played during Mughal emperor Akbar's regime.

“This rare manuscript has some text along with a box of symbols. So far, no one has managed to decode it. Many linguists and experts have visited our library, and we’ve shared the text with scholars around the world, but no one has been able to provide an answer. We hope that one day, someone will crack the code,” T Geethalakshmi, the curator of GOML, said excitedly.

Another notable manuscript in the collection is the ‘Thirumurugaatrupadai’, a devotional Tamil poem dedicated to the god Muruga, dating from the 3rd to the 6th century. This manuscript, written on a very small circular-shaped palm leaf, contains 317 legible lines. Another tiny manuscript, only 11 centimetres long and 2.5 centimetres wide, discusses astrology, particularly the importance of auspicious and inauspicious times.

The library also contains a manuscript of Tamil alphabets, created to teach children the Tamil script, and an English-Tamil dictionary used by British officials to learn Tamil during colonial times.

“In addition to preserving the manuscripts, we conduct awareness programs in villages to collect manuscripts. We also offer reference and translation services, publish newsletters, and produce magazines related to manuscripts,” Geethalakshmi told The Federal.

The rare manuscripts and books are stored in alphabetical order, with reference boxes providing summaries and detailed information about each item. All 50,000 manuscripts are meticulously verified every six months, and lemongrass oil is used to protect them from decay.

“Our primary responsibility is to preserve these manuscripts. We use cotton balls to gently wipe them and apply lemongrass oil to protect the leaves. We are also in the process of digitizing all the manuscripts here,” Geethalakshmi added.

One visitor, L Sangeetha, a student from Madurai, was fascinated by a manuscript of ‘Tolkappiyam’, the first comprehensive grammar work in Tamil, dating back to the 5th century BC.

"This Tolkappiyam manuscript has nine chapters and 1,610 verses. I couldn’t take my eyes off it. The way the verses are written and the chapters arranged on the palm leaf mesmerises me. It’s an incredible experience to read this work in the digital age," she said.

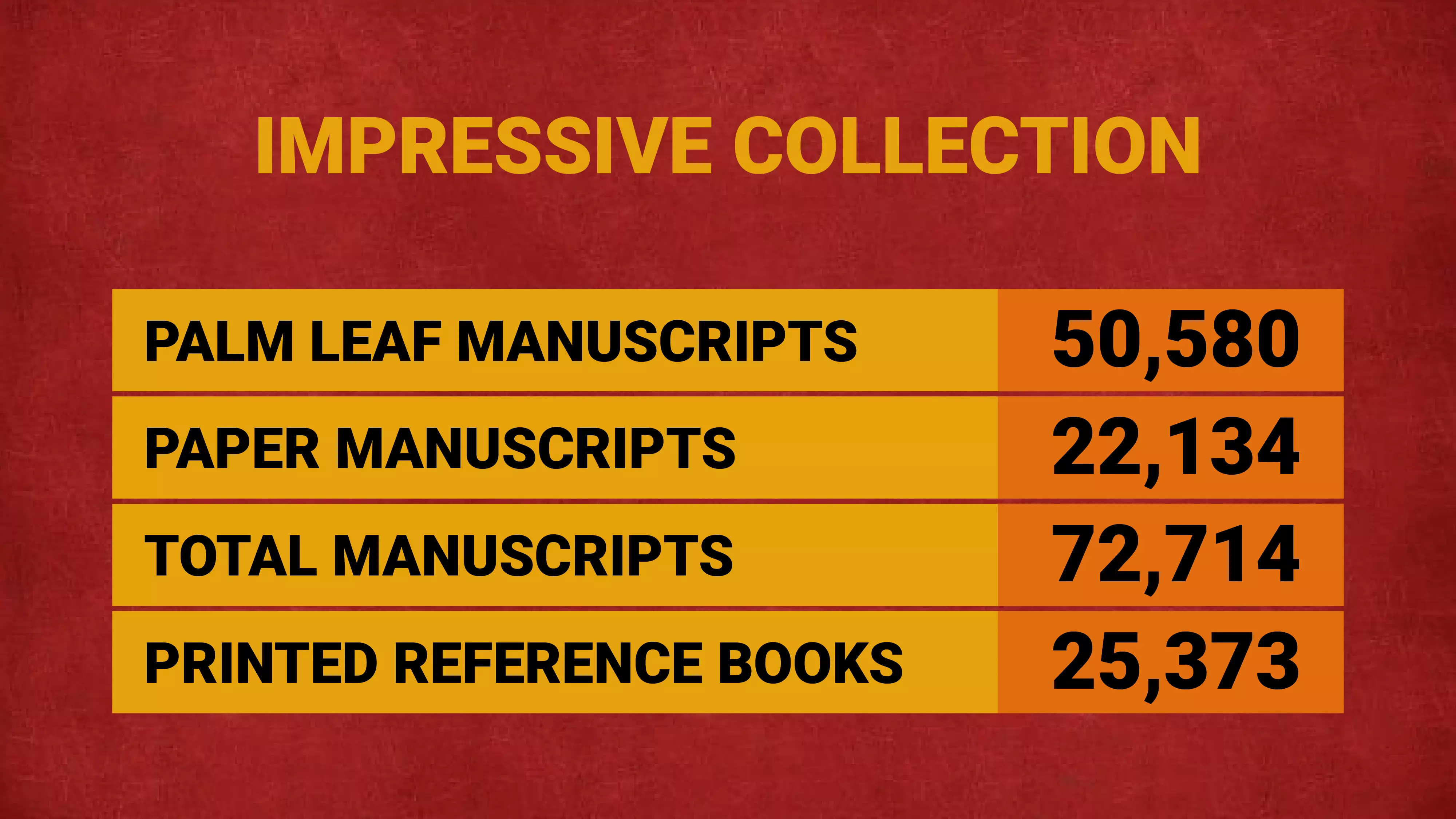

Currently, the library houses a vast collection of 50,580 palm leaf manuscripts, 22,134 paper manuscripts, and 25,373 reference books in multiple languages, including Tamil, Sanskrit, Sinhala, Telugu, Kannada, Marathi, Urdu, Arabic, and Persian. The subjects covered include mathematics, astronomy, traditional Siddha, Ayurveda, Unani medicine, Vedas, Agamas, architecture, music, sculpture, history, and grammar.

The library regularly receives requests from foreign researchers. Recent visitors include a student from the University of California, Berkeley, who was gathering information on agriculture during the Mughal period, and another student from the University of Tokyo, who sought details on traditional medicine. Scholars studying history, literature, and medicine often frequent the library. The manuscripts on topics such as veterinary medicine and chess strategies played by the kings of Mysore are also quite popular.

Another visitor R Chitradevi, a history graduate, told The Federal that this library helped her to read in-depth into the cultural and social life of people which she couldn’t learn from her text books.

“This library collection represents a treasure trove of historical, cultural, and scientific knowledge, meticulously preserved for future generations. I got details on medicines prepared for horses which were used in wars. There was a book named Navay Sathiram — which talks about techniques used to build a ship. The details on measurements and money used for trade amazed me,” she said.

The library employs eight language experts to assist students and researchers in deciphering the texts. Urdu expert Syed Moinuddin explained two rare Persian manuscripts that are frequently requested by visitors — the Diwan E Tharkam, which details musical instruments used during the reign of Emperor Akbar, and the Mukhtaran-Al-Tibb, which contains information about Unani medicine.

“Traditional Unani doctors have used the details in these manuscripts for centuries. The therapies, diet recommendations, and medicinal preparations mentioned in these works are still used today. We preserve these manuscripts with great care, and we've also digitized the information for future reference,” he told The Federal.