- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

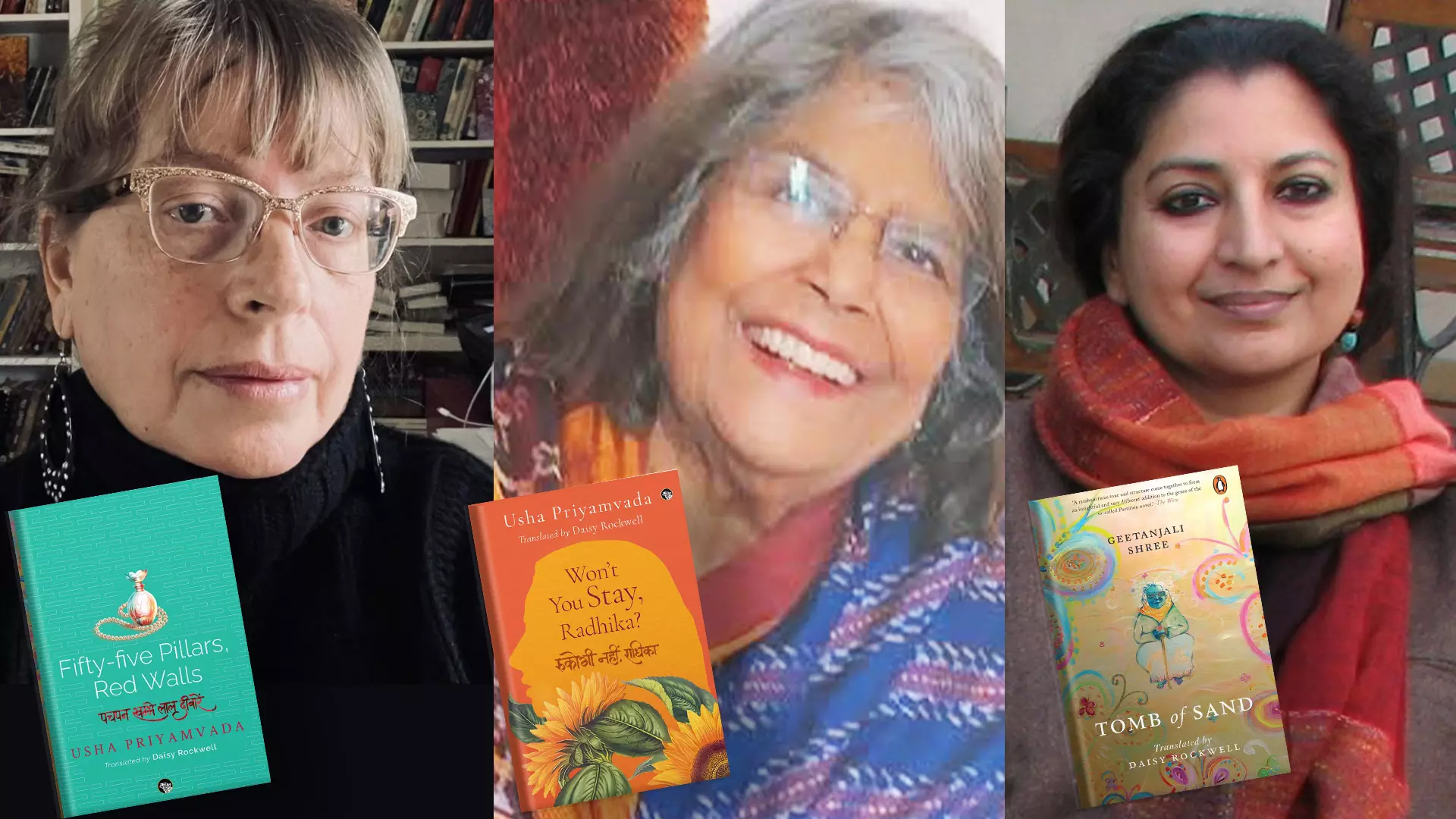

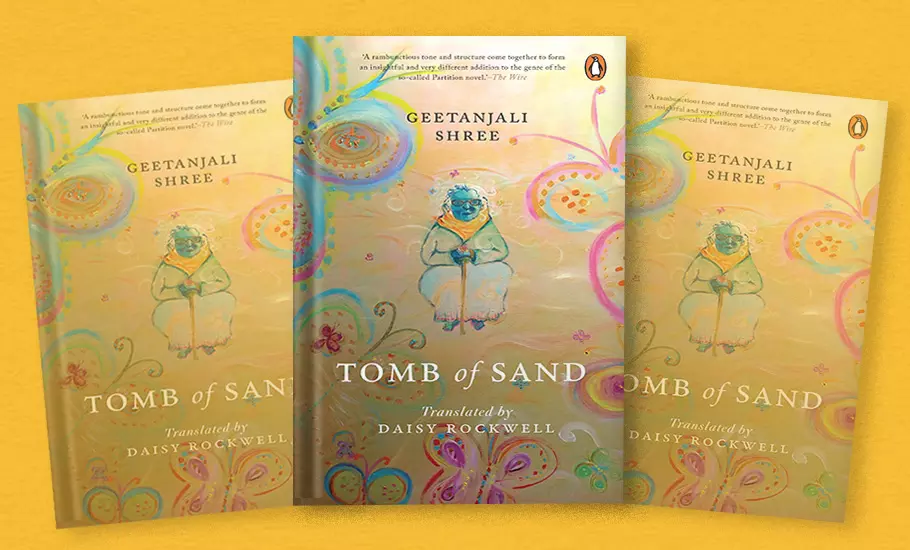

Who do you think of when you think of Hindi fiction writers? In the wake of the 2022 International Booker Prize, perhaps the first name that would come unbidden to your mind is of Geetanjali Shree, who won it for her novel, Tomb of Sand (translated from Ret Ki Samadhi by Daisy Rockwell), the first work of Hindi fiction to bask in the glow of attention and praise from readers around the world....

Who do you think of when you think of Hindi fiction writers? In the wake of the 2022 International Booker Prize, perhaps the first name that would come unbidden to your mind is of Geetanjali Shree, who won it for her novel, Tomb of Sand (translated from Ret Ki Samadhi by Daisy Rockwell), the first work of Hindi fiction to bask in the glow of attention and praise from readers around the world. If you think a little more, you can come up with Munshi Premchand, who portrayed the oppression of women, and the pervasive discrimination against people on the margins, in his suffused-with-realism novels like Godan, Gaban, Nirmala and Sevasadan.

If you are a fan of historical epic fantasies, you will name Devaki Nandan Khatri, who wrote Chandrakanta, considered to be the first modern Hindi novel, in 1888. You’ll perhaps also name Jaishankar Prasad, one of the pioneers of Romanticism in Hindi literature, or Yashpal or Jainendra Kumar or Bhisham Sahni or Phanishwarnath Renu or Dharamvir Bharati or Kamleshwar or Kashinath Singh or Narendra Kohli. If you have discovered Hindi literature largely through translations, names like Mahadevi Verma, Mannu Bhandari or Kanta Bharti will not occur to you.

For far too long, the Hindi literary world has been dominated by male voices, relegating women writers to the shadows. While translation serves as a bridge between languages and cultures, for many years, it played a limited role in bringing Hindi women writers to the forefront of global literature; translation of Hindi literature into English remained scarce, and subpar that failed to capture the essence of the original work. In recent years, however, there has been a palpable shift in the Hindi literary landscape. With relatively eager and receptive publishing and translation apparatuses, women fiction writers are now getting the recognition they deserve.

Geetanjali Shree who won the 2022 International Booker Prize for her novel Tomb of Sand (translated from Ret Ki Samadhi by Daisy Rockwell).

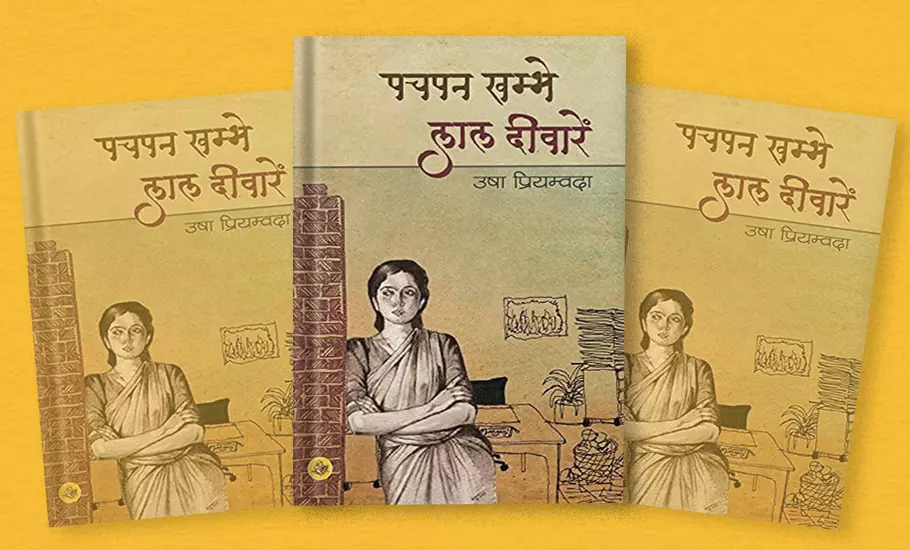

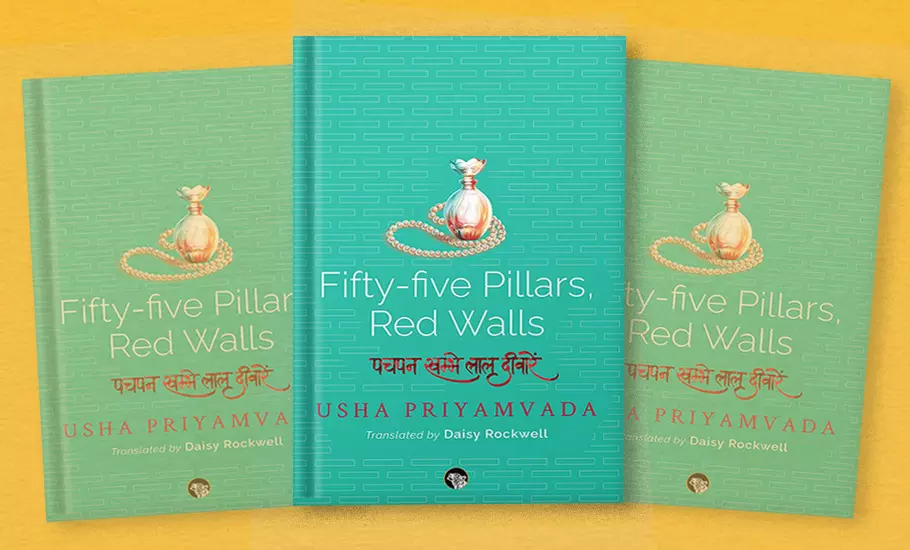

A year before Tomb of Sand was published in the UK by Tilted Axis Press, a non-profit British publisher on avowed ‘mission to shake up contemporary international literature,’ and subsequently won the International Booker, Rockwell translated Usha Priyamvada’s debut novel, Pachpan Khambe, Laal Deewaarein (Fifty-five Pillars, Red Walls, Speaking Tiger Books), set within the boundaries of an all-women’s college in Delhi, which closely resembles Lady Shri Ram College, where Priyamvada taught for three years. Born in Kanpur, she went to the US after she won a Fulbright fellowship to study comparative literature at the University of Indiana. Until her retirement in 2002, she taught at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, for decades.

First published in 1961, Pachpan Khambe, Laal Deewaarein, much like her other works, provides concise and keenly observed glimpses into the world of educated middle-class women, exploring the themes of desire, ennui, and loneliness. “Her work has enjoyed immense popularity with women readers in Hindi, but garnered scant attention from critics. Like many chroniclers of women’s lives around the world, Usha has been relegated to the category of ‘lady writer’ despite the sophistication of her writing and her distinctive feminist protagonists,” writes Rockwell, adding that the novel is something of a cult classic in Hindi, and a seminal feminist work that also explores the complex inter-relationship of financial freedom and familial obligation.

Daisy Rockwell translated Usha Priyamvada’s debut novel Pachpan Khambe.

The story centres on Sushma Sharma, a brilliant young lecturer and hostel warden. The title refers to the distinctive college architecture, which Sushma eventually perceives as a beautiful yet confining prison. In her early thirties, Sushma has achieved remarkable success in her career, but grapples with isolation and loneliness. Her family, on the brink of financial hardship, relies on her income as her father’s pension is insufficient to support them and provide for her sisters’ marriages. Given the family’s circumstances, Sushma, as the eldest, was allowed to pursue an academic career. However, her mother opposes her marriage, fearing that she might quit her job and stop supporting the family.

Despite taking pride in her accomplishments and responsibilities, Sushma experiences a profound sense of loss, realizing that she may never marry and will lead a solitary life. Her dilemma when she falls in love reflects a common concern for educated working women of her time, who had to balance work and marriage, often forced to make a choice between the two. Sushma’s family, by allowing her to work instead of arranging her marriage, has not granted her freedom but has instead found a way to exploit her as a valuable asset.

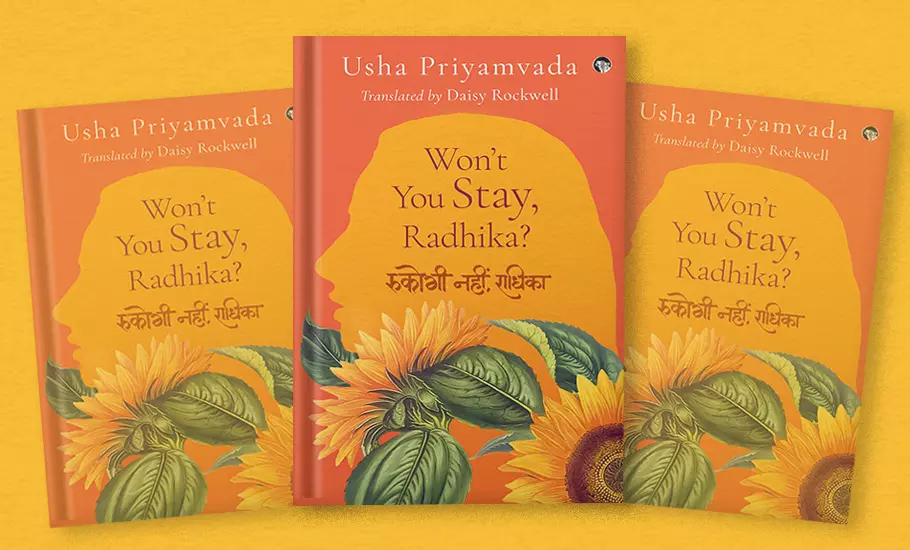

In August this year, Rockwell translated another of Priyamvada’s novels: Rukogi Nahin Radhika (Won’t You Stay, Radhika, Speaking Tiger Books). First published in 1967, the novel, according to Rockwell, is probably one of the earliest instances in Hindi of diaspora literature. It is the story of a woman named Radhika, whose world is upended when her widowed father marries a younger woman. This shatters the emotional and intellectual bond they shared since her mother’s death, leaving Radhika feeling betrayed. To escape the unbearable tension at home and the growing divide with her father, she moves to Chicago for her master’s in fine arts.

Upon her return to India two years later, she is burdened by alienation and homesickness. She discovers that while nothing has changed in her country, everything has. The family she longed to reunite with barely acknowledges her arrival, and she feels a profound lack of belonging. As time passes, Radhika’s life becomes mired in ennui, casting a pall over her romantic and familial relationships. She finds herself lying on her takht, bored, immobile, and uninspired. “Filled with a sense of alienation in Chicago, she longs to return to India, hoping for a sense of belonging. But the return, as has since so often been recorded, is alienating as well, leaving her in an emotional state of in-between-ness, of universal unbelonging. A sense of alienation is also famously a hallmark of Hindi literature of the 1960s,” Rockwell writes in her Introduction.

In 2019, Rockwell also translated the final novel by Krishna Sobti, the most respected woman writer in the Hindi canon. A Gujarat Here, a Gujarat, published by Penguin, is a compelling novel, set during the tumultuous time of Partition, which follows the journey of Krishna, a young woman who seeks refuge from the chaos in Delhi by taking a job at a preschool in the princely state of Sirohi. It delves into the challenges she faces due to her refugee status and gender bias, as well as her unexpected opportunity to become the governess to the young maharaja. The novel blends fiction, memoir, and feminist commentary to illuminate the effects of Partition and the struggle for individual freedom. Through Krishna’s story, it addresses themes of identity, belonging, and the quest for autonomy.

At some point in the novel, Sobti talks of Partition in a stream of words and phrases, interspersing her own family’s experiences with observations about refugees and migrants. “Who’s the sinner? Who’s the criminal? Who is witness to the crime? One dagger-plunging hand. Another, match-striking, lighting an oil-soaked rag. One stands far off, gathering a crowd. A clutch of terrified men and women holding their breath in a jungle of half-dead, frightened voices: They just came — we just went — we just died — don’t make a sound. Let them pass by. Piles upon piles of corpses, mounting ever higher. A wake of vultures roots about. Rings on hands grown cold; necklaces encircle throats.”

Rockwell tells us that in these particular lines — spare and elegant — Sobti enters “the minds of the mobs, migrants, those fleeing and those chasing, those attacking and those under attack.” “While other authors have spilled buckets of ink writing histories and novels about the Partition, Sobti attempts to use the smallest amount of ink possible, to cut the story of migrancy and violence down to the bone. Even Manto rarely managed so few words in his Siyah Hashiye (Black Borders), his ultra-short stories of the Partition,” says Rockwell.

Sobti’s magnum opus, Zindaginama (HarperCollins, 2016), translated by Neer Kanwal Mani and Moyna Mazumdar, is set in a small village called Shahpur in undivided Punjab during the early 20th century. It revolves around the lives of its inhabitants. As the Ghadar Movement gains momentum across Punjab and Bengal, revealing British colonial excesses, Shahpur can no longer remain isolated from the mounting discontent: the harmonious coexistence between people of different faiths is at threat of being ruptured.

In August this year, Daisy Rockwell translated Priyamvada’s Rukogi Nahin Radhika (Won’t You Stay).

“One fateful morning, I woke up with echoes of azaan in my ears, and before my eyes stood one minaret of the village mosque. I knew instinctively that I was committed to carrying the powerful internal echo of this voice through the century. While writing Zindaginama, I tried to focus on a precise visual and dramatic recall of peasant speech. The simple use of the visible and the audible created a world of its own. All I wanted was to paint the surge of humanity — their strong rustic faces, their noise. Yes, I had to create their speech — rough, potent, verbal — with the help of their spoken words and diction,” Sobti writes.

“Zindaginama is …. a giant patchwork tapestry in rich warm colours and vivid detail, that depicts the life and times of a small village in pre-Partition Punjab — a Punjab that once spread across the five divisions of Rawalpindi, Multan, Lahore, Jalandhar and Ambala. That world, that way of life, no longer exists, neither in India, nor in Pakistan. Much has changed in the last hundred years — the schism that ripped through the land as final as a Tectonic-shift — yet the past, beautifully evoked in this book, sparks the depths of our collective memory, hearkening back to a bond that predates the bitter events of recent history and puts the focus on a kinship that our souls intuitively thrill to and instinctively recognize,” the translators write in their note.

Zindaginama was originally conceived of as a trilogy. The first part was called Zinda Rukh (The Living Tree) and published in 1979. The latter two parts were never written, but the blueprint for the original trilogy has been outlined in the prologue, which has been written in poetic form.

Hindi women writers like Sobti were lucky. Things worked out differently for writers of the previous generation like Kanta Bharti (1935-2001), the first wife of Dharamvir Bharati, who is celebrated in the Hindi world for his novel Gunahon Ka Devta (The God of Sins), which was published in 1949. A love story set in Allahabad during the British rule in India, it explores complex human emotions and relationships through the story of four main characters: Chandar, Sudha, Vinti and Pammi. It is believed that the protagonist Chandar is a portrayal of Dharamveer Bharti himself. After 16 years of the publication of the novel, Kanta Bharti wrote a novel, Ret Ki Machhli, about marital discord, after their divorce, but it did not see the light of day until her death. It is said that Dharamvir Bharati, an influential figure of his time, did not let the novel get published and it came out four years after his death in 1997.

There must have been many Kanta Bhartis in the annals of time, who would have sacrificed their literary ambition at the altar of patriarchy. It is perhaps because of this that when Shree won the International Booker, her victory was not merely a personal achievement; it was a collective triumph for Hindi women writers who have been silenced, sidelined, subjugated and overshadowed for far too long.