- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

In 1955, 18-year-old MS Viraraghavan — fondly called Viru — fell in love with a shrub of Julien Potin, a popular yellow rose, which was in full bloom at the Sim’s Park in the hill town of Coonoor in Tamil Nadu. When his friends fell in love with pretty girls in the college, Viraraghavan chose to be different. He established a strong bond with roses rather than girls in the blue mountains...

In 1955, 18-year-old MS Viraraghavan — fondly called Viru — fell in love with a shrub of Julien Potin, a popular yellow rose, which was in full bloom at the Sim’s Park in the hill town of Coonoor in Tamil Nadu. When his friends fell in love with pretty girls in the college, Viraraghavan chose to be different. He established a strong bond with roses rather than girls in the blue mountains of the Western Ghats. The connection remained strong even after he joined the Indian Administrative Service in 1959. Roses dominated his thoughts, and he finally retired voluntarily from service in 1980 to dedicate his life to roses.

MS Viraraghavan, a bureaucrat-turned-rosarian, and his wife Girija have been travelling to various places in India and abroad in search of roses for the last 40 years. The couple, however, prefers not to move around during the monsoon months (from September to December) when their garden atop the Palani Hills in Kodaikanal attains a special charm in December. “The rosa gigantea plants climbing our many trees — cypress, callistemon and native magnolia — burst into spectacular bloom, in clouds of cream and white, an alternative White Christmas. There is an incredible surprise in store when suddenly the rains stop, and the sun comes out with the intense, rich brightness characteristic of mountain sunlight,” write Viraraghavan and Girija in their recently published book Roses in the Fire of Spring: Better Roses for a Warming World and other Garden Adventures, a gardening memoir documenting the journey of the renowned plant hybridizers who created roses that can thrive in the warming world.

Viru wanted to create roses for warm climates and he felt that he should start his breeding lines with the wild rose species to be found in India, in the warmer areas, not the cold Himalayas, which are home to a number of wild rose species. He had zeroed in on two species, R gigantea, which grows in Northeast India, in Manipur, and the warmer species, Rosa Clinophylla. Interestingly, Rosa Clinophylla grows in water. Even though Viru has been hybridising roses since 1965, his early aims of breeding were to raise roses in unusual colours. He has been concentrating since the 1980s on breeding with the two Indian rose species to get roses for warm climates. Result: the couple has released 118 hybrids so far with interesting names.

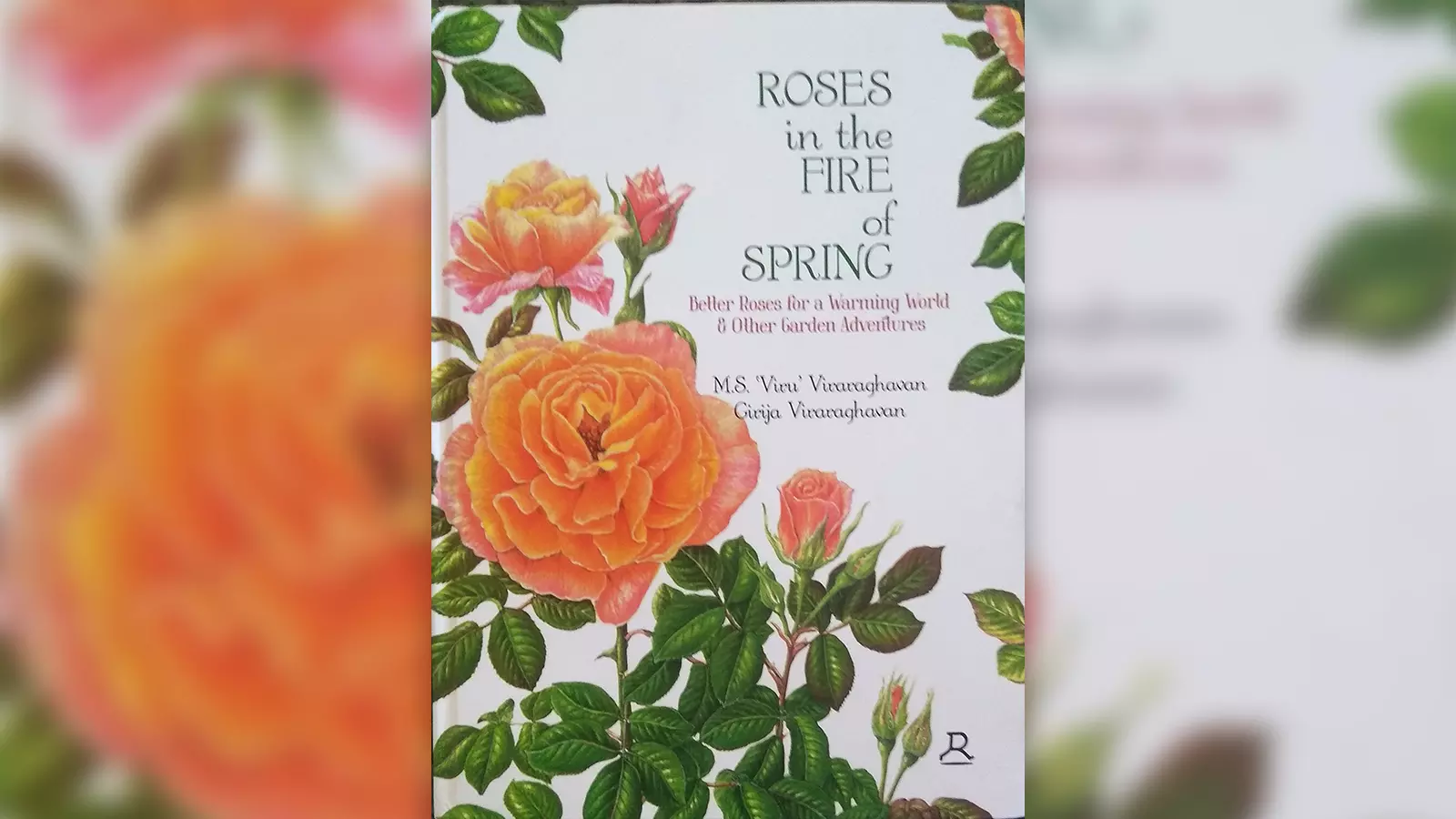

MS Viraraghavan and Girija's book Roses in the Fire of Spring: Better Roses for a Warming World and other Garden Adventures

One of the earliest examples of selection of rose varieties for warm climates is of Rose Edward. Called Panneer Roja or Thanjavur Roja, this rose is commercially cultivated extensively in the Cauvery Delta and southern Coromandel Coast, and its profuse harvest of pink fragrant flowers are used for garlands. It is one of the best roses for warm climates and underlines the importance of warm climate rose breeding and selection of new progeny for resistance to warmth. Most rosarians in India grew modern roses bred in Europe or the US.

“This preference is part of the fascination in India for whatever is imported from outside as superior. It is very obvious that we have to look for roses better suited for our climate. It is also important to remember that of all the tropical climates in southern Asia, the southern part of the Coromandel Coast, from Chennai to Kanyakumari is the most challenging of all environments to grow western roses. This area, as you all know, lies in the rain-shadow of the Western Ghats and therefore there is little rain during the South-West monsoon, in contrast to the rest of India which enjoys bountiful showers. Again, the southern Coromandel Coast being so far from the Himalayas has no winter to speak of. These factors make growing imported roses a real challenge,” said Viraraghavan, while sharing his experiences in hybridising roses for warm climates at the Roja Muthiah Research Library recently.

The enthusiasts who managed to grow imported roses, according to him, were compelled to spray hazardous fungicides and pesticides every week at considerable risk to themselves and the environment.

In India, the need for a separate line of rose breeding was stressed nearly a century ago by the country’s renowned rose breeder BS Bhattacharji. Graham Thomas, a British rosarian, pointed out that the original roses imported from China, which is considered as the source of roses from the 18th century onwards, were well adapted to warmth, and they carried with them the invaluable gene for continuous flowering.

“Both wild roses, called rose species, of which there are about 150 in different parts of the world, and the old heritage roses of Europe and the US, that is, those early hybrids from the 18th century on, were all once flowering. That is, they flowered at the most for a month or so every year, and that’s all. It was the skilful hybridisation of these once flowering roses with the continuous flowering imports from China which created modern continuous flowering roses of the temperate climates. But naturally this work carried with it an inevitable hazard. Due to the cold climate, more roses bloomed. But these roses became less and less suitable for warm climates, unlike the original Chinese imports, and the first hybrids, which are classified as Tea Roses, Noisette Roses and China Roses,” he said.

A set of new genetic input was required if the warm climate rose revolution is to be achieved. So the couple chose two Indian wild rose species, Rosa Gigantea which is to be found in the Northeast, and Rosa Clinophylla, which is native to Bengal and Bihar, to be added to their hybridising pool of roses. “We personally collected both these rose species and have worked with them for the past 30 years. The focus of this work has been the creation of such roses which would fare well in warm climates,” they said.

New roses can only be made from seed. “The rose and the apple are closely related. If you cut an apple don’t you find a seed? Similarly, after a rose flower fades and dies, sometimes a fruit is formed, which will contain seed. We consciously take the pollen from one flower and stick it on to another flower and wait to see if a fruit forms. It is the process of germination of the seed that leads to the creation of a new rose,” said the couple.

But any new rose seedling will not do – they will have to be tested for several years before being introduced as a new rose worth growing. And that’s challenging.

New roses can only be made from seed.

“We collected seeds and cuttings of the same form of Rosa Gigantea as did Sir George Watt. What General Sir Henry Collett discovered in the Shan Hills of Myanmar at the same time as George Watt discovered in Manipur—1880s, was only a different eco-type of this species. It was certainly a turning point in our breeding work since we have been able to create many new hybrids using this rose species,” Viru and Girija told The Federal.

While Viraraghavan’s association with roses began in the early 1950s, Girija fell in love with the flower after the couple started growing roses together in the 1960s. “Since he was in government service, he would leave for his office in the morning after finishing the rose breeding work, which are called ‘rose crosses’, but sometimes the work could not be completed by the time he had to leave for work, and then I would finish the work. I would also help him keep the records of all the breeding work in yearly diaries,” said Girija.

Hybridising roses is an art in itself but it needs patience. When the couple started hybridising with Rosa Clinophylla and Rosa Gigantea, they had to first get the plants of the species, grow them to a size when they began to flower (five-six years), then they had to make the crosses with them and other roses. “After we finish doing the actual crossing, that is, removing the pollen of the rose flower which we use as a seeder-mother-parent, then at the right time, when the pollen of the flower which we want to use as the pollen or male or father parent is ready, that means the pollen has started dehiscing, which happens a few hours after collecting the pollen from the flower and when we touch the pollen, a yellow powder sticks to the fingers, then the pollen is ready,” said Viru.

The pollen is then put on the flower of the species or any other flower which has been prepared by removing its pollen. One needs to wait a few weeks to see if the ‘cross’ has ‘taken’. It happens, when the flower petals have fallen off, and the portion below the petals, which looks like a little cup which is called the rose hip and is green in colour, begins to swell up. If the ‘cross’ has not ‘taken’, the rose hip will fall off the stem just as the flower also has fallen off after it has withered. Then it has been a failure. But if the hip begins to get fatter, then it means the cross has taken. One needs to wait about six months for this hip to become orange in colour. Then, one can harvest this hip, cut it open and remove any seeds which are there.

Uncertainty plays a major role here. Sometimes there will be no seeds, sometimes just one or two and sometimes a few. One needs to collect the seeds and then keep each set of seeds separately in small palettes, for a few days to dry out. “We sow the seeds in black plastic seedling trays which have little cup shaped grooves, so we can sow the seed on the soil filled in each groove, it is a special soil mixture, and then we label each set of seeds so we know what the cross—the two parents are. And we record all this in a diary,” he added.

The job never ends there. Sometimes the seeds will begin to sprout within a month, sometimes they may take a year or more. After the baby seedlings have grown to about three-four inches, one needs to take them out from the plastic seedling trays and pot them or bag them in small pots/black bags. As they grow bigger one needs to keep transferring them to bigger and bigger pots or bags. “We then wait to see how they perform, the colour of the flowers etc. If a seedling looks promising, we give it extra attention. But we wait for eight to nine years to observe the seedlings. Only after this time of observation and testing to ensure that the plant is healthy, grows well, gives a number of flowers, and the flower colour is good, and the plant is disease resistant, that we decide to release it,” said the rosarian couple. “We give the plant a name, write down all the various characteristics of the whole plant and flower including size, foliage, thorns, etc, and send these details to the International Rose Registration Authority and a website called HelpMeFind.com/roses. These details are entered along with all the photographs we send. We also send cuttings to nurseries in India for them to make more plants, catalogue them and sell them. But we do not get any money out of all this. Just the joy of knowing that our roses are being grown widely keeps us motivated,” they added.

When a rose is released, it will also be named after some prominent place or person, mostly connected to the botanical world. ‘Manipur Magic’ is the name given to Rosa Gigantea, which the couple located during their visit to the Sirohi mountain in Manipur. ‘Tangkhul Treasure’ has been named after the Tangkhul Nagas, a dominant tribe in Manipur. ‘Sir George Watt’ was named as a tribute to the discoverer of Rosa Gigantea in 1882. ‘Sir Henry Collett’ is named after the general in the British India Army who discovered R Gigantea in the Shan Hills of Burma. While ‘Golden Threshold’, grown by Radosav Petrović in Serbia, was named after Sarojini Naidu's book of poems and her house in Hyderabad, ‘Amber Cloud’ derives its name from a lavish display of this rose in Nicoletta Campanelli’s garden in Italy. “Sakura Sunset” is named as a tribute to the Sakura Rose Garden, Japan. ‘Naga Belle’ is named to reflect the beauty of the Naga women who live in Manipur. ‘Sirohi Sunrise’ is named after the couple’s expedition to Mt Sirohi to look for Rosa Gigantea. ‘Kindly Light’ is inspired by the well-known hymn, “Lead Kindly Light”. ‘Agnimitra’ (Friend of fire) was a great king of ancient India. There is a hybrid named ‘EK Janaki Ammal’, to honour the great plant geneticist.

Hybridising roses is an art in itself but it needs patience.

For Viru and Girija, warm climate roses have been both the dream and goal. All these years only western roses, which are meant for cold climates, were being grown in India. It is only now that slowly Indian bred roses too are being grown, thanks to Viru and Girija. The couple’s garden in Kodaikanal contains many different plants, trees, climbers and shrubs. It has magnolias, camellias, rare trees, climbers of different kinds, rhododendrons which too they have hybridised with, gerberas and umpteen other plants, apart from our thousands of rose seedlings and the mother plants of their own bred roses.

For this rosarian couple, the indulgence with roses never ends. “The lockdownhelped us to focus on our book Roses in the Fire of Spring, which is out now. The thrust of our book is on creating new and better roses for warm climates. It presents a country-wise list of future possibilities in rose breeding in places as diverse as China, subtropical Asia, Africa and the Middle East. We have included our findings and experiences in the book,” said Girija.