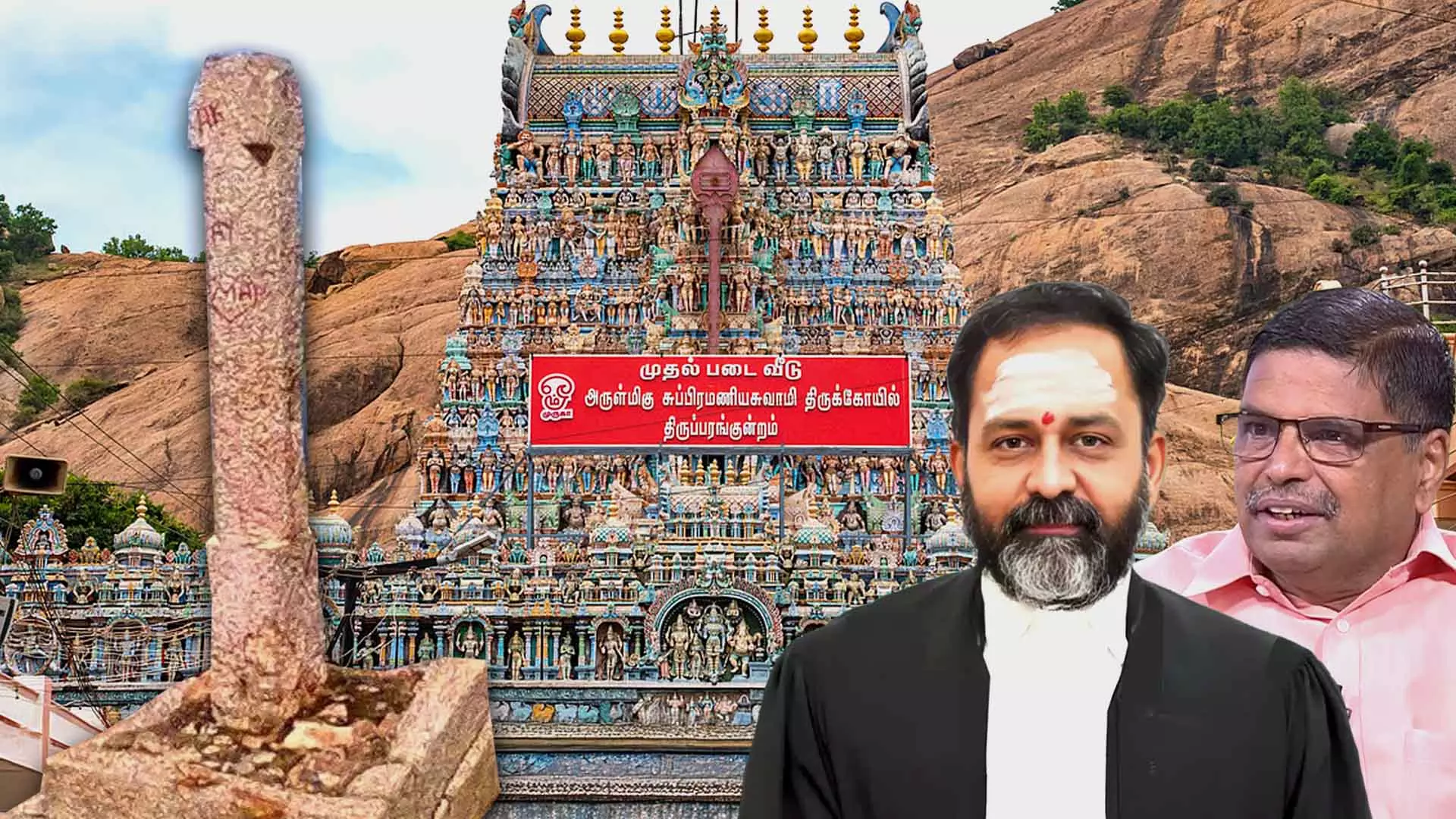

Thiruparankundram row: Why the urgency? Former justice D Hariparanthaman flags haste

Former judge questions last-minute judicial orders in sensitive religious matters and says ignoring binding judgments undermines judicial discipline in Tamil Nadu

The Thirupurankundram Deepam lighting dispute has triggered intense legal, political, and social debate in Tamil Nadu, raising questions about judicial discipline, public order, and the limits of court intervention in religious matters.

The Federal spoke to a retired judge of the Madras High Court, Justice Hariparanthaman, to understand the constitutional, legal, and institutional concerns emerging from the controversy and its wider implications.

The Thirupurankundram Deepam case has been in court for nearly a month. How can a state government refuse to implement a court order?

To answer this, one must first go back to the background of the case. There were five cases in total, though one stood apart, and a common order was passed on December 1, 2025. December 3 was Karthigai Deepam day, and since the order came at the last minute, there was effectively no time to file an appeal.

This is not a case where the Tamil Nadu government openly declared it would not obey a court order. The criticism here is different. The concern is that the judge passed directions at the last moment, exerting pressure on the administration in a matter deeply connected to religion, sensitivity, and public order.

The judge has said the government is hiding behind law and order and communal harmony. How do you respond to that?

Law and order is not an excuse; it is a constitutional obligation. The same Deepam issue arose earlier, including in 2014. Even this year, on December 3, the Murugan temple lit the Deepam at the traditional place. The judge did not question that.

What the judge directed was something additional that apart from the customary location, the Deepam should also be lit at another place near a pillar. That is the crux of the dispute.

What do earlier judgments say about where the Deepam should be lit?

This issue goes back decades. There were cases in 1996, then again in 2014, and appeals thereafter. Two division bench judgments are crucial.

Also read: TN: Thiruparankundram residents reject ‘Ayodhya of the South’ pitch

A single judge order of 2014 went on appeal. In July 2017, Justice Satish Kumar held that the place where the Deepam is to be lit must be decided solely by the temple administration. He also clearly stated that law and order is a relevant consideration.

In December 2017, a division bench comprising Justice Kalyanasundaram and Justice Bhavani Subramanian delivered a detailed judgment. They rejected arguments that lighting the Deepam at Ucchipillaiyar Koil was against Agamas and noted that the practice had continued for over 100 years. They explicitly said communal harmony must not be disturbed.

Do you believe these binding judgments were ignored?

Yes. These judgments arose directly on the same issue. Yet, they were not discussed. Ignoring binding division bench judgments amounts to a lack of judicial discipline.

This is not an isolated instance. A similar pattern was seen in Karur in 2024. A ritual that had been prohibited by a division bench in 2015 was suddenly allowed at the last minute. The event took place, and later a higher bench set aside the order. Such urgency in sensitive religious matters is deeply problematic.

The judge's supporters say he has disposed of a very large number of cases efficiently. How do you view that argument?

Numbers do not define justice. Even one judgment can echo forever. Many of the cases disposed of were routine matters such as pensions or service issues.

The concern is selective urgency. Does the same urgency apply to all cases? For instance, if a widow seeks a pension, does the court demand payment the very next day? No. But in these religiously sensitive cases, extraordinary haste is shown.

You have raised questions about the timing of the petitions. Why does that matter?

The Karthigai Deepam dates are known well in advance at least eight months earlier, through the Panchangam. Yet, petitions were filed at the eleventh hour.

One petition was filed on November 7, numbered on November 10, and disposed of by November 28. Other petitions were filed between November 17 and 21, and were also disposed of in the same common judgment. In some cases, there were barely seven days between filing and reserving orders.

Also read: Why was my order ignored? Justice slams TN officials on Thiruparankundram row

This raises concerns about forum shopping and undue haste.

Were procedural norms followed in disposing of these writ petitions?

In writ proceedings, courts may grant interim relief, but final disposal requires adherence to High Court rules. Parties sought time and even filed memos requesting time. Yet, final orders were passed.

Several parties, including the Wakf Board, were impleaded just a day before the judgment. How can such parties meaningfully respond, study documents, consult counsel, and present arguments in such a short time? This goes against principles of natural justice.

What about the contempt proceedings that followed?

The contempt proceedings were highly unusual. They were listed repeatedly — on December 3, 4, 5, and then December 9. Normally, courts grant reasonable time.

Senior officials like the chief secretary and the additional director general of police were asked to appear, even though they were not parties to the writ petitions.

The court used terms like “total breakdown of law and order” and “failure of constitutional machinery,” which are serious political and constitutional expressions associated with Article 356.

You have pointed to inconsistency in how similar cases were handled. Can you explain?

Yes. Around the same time, the judge dealt with cases from Perumal Patti in Dindigul and from Kanyakumari, both involving Christian institutions.

In Perumal Patti, despite multiple FIRs, lack of formal structure, and prohibitory orders, permission was granted to light a Deepam. In Kanyakumari, the collector’s order preventing installation of a Murugan statue was set aside without even hearing the collector.

In contrast, in another case involving alleged illegal church construction without collector permission, the absence of permission was treated as decisive. The standards applied were not uniform.

From a constitutional perspective, how should courts approach such sensitive religious disputes?

Article 25 guarantees freedom of religion, but it is explicitly subject to public order, morality, and health. No right under Article 25 is absolute.

Earlier division benches correctly applied this principle. Section 28 of the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Act also places responsibility on the temple administration to decide matters based on usage, custom, and practice. These principles were overlooked.

Should this dispute have been decided by a civil court instead of writ proceedings?

Yes. This dispute involves questions of property, boundaries, and customary rights. Such matters are best decided by civil courts after examining evidence.

Also read: Thiruparankundram deepam row: Madurai bench refuses to stay single judge order

A civil court judgment from 1923, later upheld by the Privy Council, had already determined ownership of different portions of the Thirupurankundram hill.

If a new practice is claimed, it must be established through a civil suit, not through last-minute writ petitions.

There are fears on the ground that Thirupurankundram could become another Ayodhya. How serious is this concern?

This fear is real. Traders have suffered losses, protests have disrupted normal life, and tensions have risen. Earlier benches explicitly warned against disturbing communal harmony.

Courts must be conscious that their orders do not escalate social tensions. That responsibility is central to judicial decision-making.

DMK and INDIA bloc MPs have moved an impeachment motion against the judge. Is that crossing a constitutional line?

No. The Constitution permits MPs to move impeachment motions. While such motions may not succeed numerically, they open up debate.

For the first time in 75 years, three impeachment motions are pending simultaneously. This itself reflects serious institutional concern. Parliamentarians have a constitutional right to raise these issues.

Is there a misrepresentation that the government stopped the Deepam altogether?

Yes. The Deepam was lit at the traditional place, as it has been for decades. The dispute is only about lighting it at an additional place near a mosque or dargah, which the temple administration opposed.

This distinction is being deliberately blurred in public discourse across the country.

The judge personally inspected the site. Doesn’t that show sincerity and effort?

A judge may inspect a site, but procedure matters. Such inspections should be conducted with all parties present or through an advocate commissioner. Private inspections without records or participation of parties raise serious procedural concerns.

Has this issue become more political than religious?

Yes. This is no longer a purely religious issue. It has been politicised, much like earlier flashpoints. Ideology is not the issue; allowing ideology to influence judicial conduct is.

Judges may hold personal beliefs, but those beliefs must not reflect in judicial orders.

Do you believe representation in the judiciary affects how such cases are handled?

Yes. India’s higher judiciary has long been dominated by upper castes. Representation of Scheduled Castes, OBCs, minorities, and women remains abysmally low.

A more representative judiciary brings greater sensitivity and balance. Democracy demands that all sections of society see themselves reflected in institutions of power.

The content above has been transcribed using a fine-tuned AI model. To ensure accuracy, quality, and editorial integrity, we employ a Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) process. While AI assists in creating the initial draft, our experienced editorial team carefully reviews, edits, and refines the content before publication. At The Federal, we combine the efficiency of AI with the expertise of human editors to deliver reliable and insightful journalism.