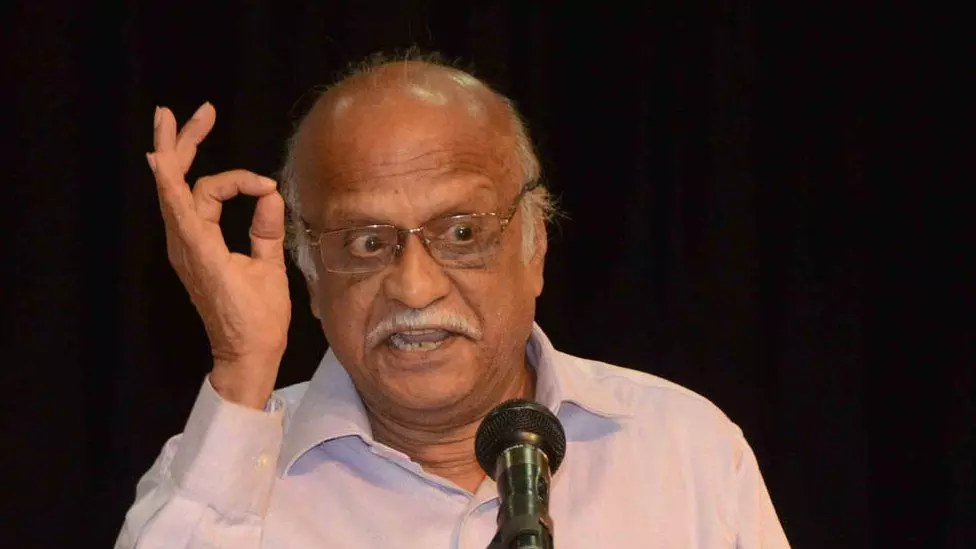

Kalburgi’s ideas find blazing power after his assassination

The assassination, the protests, the high profile media coverage and the police hunt that followed drew attention to his work

Dr MM Kalburgi was shot dead by two assassins on August 30, 2015, and eight years later, the trial of his alleged killers is still unfolding.

The police chargesheet mentions that Kalburgi, in a speech, had quoted a controversial statement made by celebrated writer UR Ananthamurthy, enraging his killers. The post-2014 media saw an opportunity to fix the outspoken academic and ran the controversy for days whipping up hate.

A close friend of Kalburgi said, “He got carried away, added an unwarranted spin to Ananthamurthy’s statement, and ended up making a highly offensive comment. He got into huge trouble, faced cases in different places, and spent lakhs to fight them. He paid a heavy price for a moment of indiscretion. But was he killed for that? The answer is a definite no.”

Many of Kalburgi’s associates point out that he faced serious threats well before the controversy. “He had been given police protection five years before he was killed, which he later gave up,” says retired IAS officer SM Jamdar, who is also the general secretary of Jagatika Lingayat Mahasabha, an organisation fighting for separate Lingayat religion.

Almost everyone this reporter spoke to said that larger interests were at play in silencing Kalburgi. They believe that the direction in which his later research was heading and its disruptive potential was making many nervous.

Controversy’s child

Over his long career Kalburgi believed that it was important to speak the truth as he saw it without worrying about the consequences. He would say “Society is larger than the individual and truth is bigger than the society as it would eventually serve the collective better.”

Kalburgi’s unflinching loyalty to his research findings coupled with his gutsy, fearless personality frequently landed him in trouble. In the late ‘80s he had made national news when he was hauled up by thousands of followers of a Lingayat matha, who found a few of his arguments unpalatable. He was forced to retract with an apology, which he described as his “intellectual suicide”.

Kalburgi did not let the controversies overshadow his work, which even his critics acknowledged as phenomenal, multidisciplinary and extraordinarily prolific. His wide ranging papers on epigraphy, literature, palaeography, linguistics and onomastics have been recently brought out in 15 volumes running into thousands of pages.

A charismatic institution builder, he lobbied with the government to support research, turned many mathas into publishing houses and mentored as many papers as he himself wrote. He could assemble large teams and put them on multi-year projects. He brought out comprehensive editions of Vachanas, the Lingayat sacred text, thrice over the decades, painstakingly updating new discoveries and filtering out fake entries. He initiated a 19-volume translation of Adilshahi literature from Persian, Urdu and Deccani into Kannada.

Silence in history

In an interview, Kalburgi had said the silence you see in history is not the silence of harmony but a silence that is enforced. Breaking the silence compelled by dominant narratives was a priority that directed his research and turned him into a consistent champion of the underdog. He also believed that to understand history, besides looking into the facts, you had to ask who had written that narrative.

The memory of the destruction of the temples in Hampi is burnt into the South Indian mind as a tragedy inflicted by the Muslim invaders. Kalburgi challenged the Hindu-Muslim binary in this narrative by pointing out that it was the Vaishnava temples that were destroyed in the conflict, which left many Shaiva temples untouched. His research documented the sweeping shift in the religious allegiance of later Hampi kings towards Vaishnavism, which alienated Shaivites, the original inhabitants of the empire, and suggested a new dimension to the strife.

A groundbreaking paper marshalled inscriptions and manuscripts to document how Jains, Shaivas, and Vaishnavas destroyed each other’s temples in ancient Karnataka. Except for Buddhists, who were usually at the receiving end, all other religious groups, including Muslims and Christians, were guilty of extreme religious intolerance in history.

The unhappy lot of Kannada in its own homeland was another recurring theme in his research. He showed how Kannadiga kings fell for the charms of other languages such as Sanskrit, Telugu and Tamil and neglected their mother tongue throughout history. The hold of alien languages and culture, among other things, had made Kannadigas embrace tolerance for survival than grow a spine.

Kalburgi could extract interesting narratives from dry historical data. He observed that the inscriptions that made grants to Brahmins spoke an ornate language. The Hero stones, which were erected to celebrate the fallen soldiers followed a simple visual template with skeletal text. The Masti stones, which paid homage to the women who committed sati, were so rustic that it was hard to distinguish even the nose and ears of the unfortunate women.

Kalburgi’s works did not meet with uncritical acclaim nor did he ask for it. The close friend said Kalburgi was not a trained historian and often confused hypotheses for conclusions. In his defence Kalburgi argued that whatever he had done was just a ‘comma’ or a ‘semicolon’ and it was for others to put a ‘full stop’. But there is consensus that when it comes to setting a research agenda for prompting future scholars to prove or refute none gets close to Kalburgi.

Rewriting Lingayat history

Kalburgi’s most rigorous and influential research came after his retirement, the one that perhaps claimed his life. Though he had balanced his interest on Lingayats along with other research concerns throughout his career, after retiring as the Vice-Chancellor of Hampi University he got into a mission mode on the subject. “He chose to devote himself to socially relevant research and set out to clear the ideological confusions of the Lingayat movement,” says Dr Veeranna Rajur, who is widely seen as Kalburgi’s intellectual successor.

Kalburgi was devoted to Basavanna, the founder of the working class religion that became a sensation in the 12th century. He was soaked in the ideals of the founding movement, which broke away from mainstream Hinduism rejecting its discriminatory beliefs and practices. The rebellion triggered a civil war and forced Lingayats to flee the medieval city of Kalyana where it all had started.

The movement’s stand against caste, divine kingship, patriarchy, concentration of wealth and rituals, including temple worship, had a natural appeal for Kalburgi, who had socialist leanings. “He did not see Basavanna as a religious leader but as a social reformer who created a movement to ensure equality, literacy, freedom of speech for all people,” says Rajur.

Though the struggle for separate Lingayat religion preceded Kalburgi by a century, the early history of the movement remained an enigma. If Lingayats had rejected Hinduism and become a separate religion how did they still have castes and followed many Hindu practices? What was their equation with Veerashaivas, who appear like a high ranking subcaste and claim an ever growing clout?

Till Kalburgi arrived scholars had believed that after making a radical exit Lingayats had gradually returned to the religion that overwhelmingly enveloped them. Sifting through thousands of inscriptions and manuscripts, Kalburgi argued that Lingayats had not relapsed but fallen prey to a centuries-long manoeuvre to gain control over them by reinjecting Hindu rituals and identity.

An Agamika Shaiva Brahmin sect, Aradhyas, who were highly influential in the neighbouring Andhra Pradesh, had joined Basavanna’s movement. But they retained their distinct identity and religious practices, and overtime transformed into a priestly caste in the Lingayat community. To entrench their position they reintroduced Hindu rituals and Sanskrit, started calling their new religious mix, Veerashaiva, and set up five mathas, Panchacharyas, to popularise it. They rewrote Vachanas and Agamas to make Panchacharyas more ancient and exalted than Basavanna, who was demoted to the status of their disciple.

Kalburgi argued with evidence that Panchacharyas and Veerashaivas sprung up in the 15th and 16th centuries, 400 years after the original movement. They had grown in influence by manufacturing myths to capture other extant Shaiva traditions and sought to replace the egalitarian and meditative Lingayat religion with a hierarchical and ritualistic Veerashaiva version, an appropriation that continues to this day.

He conceived Lingayat as a Kannada-speaking indigenous religion with a distinct philosophical framework and social base encompassing castes across the spectrum. He discouraged upper caste behaviour of Lingayats, urging them to realise their history and embrace the downtrodden groups, who were still devoted to Basavanna.

Red flag goes up

The recovery of Lingayat history was a red flag for many as it had the potential to infuse revolutionary zeal to a large South Indian community. Most Lingayats, however saffronised, retain huge affection for Basavanna and here was Kalburgi reigniting the founder’s radical message. It is not just the Hindutva groups, even the majority of the rich and influential Veerashaiva and Lingayat mathas, which are wary of reviving Basavanna’s influence. “The opposition from forces within the community was more intense than the opposition from outside,” says Dr Kalyanrao Patil, who did his PhD under Kalburgi.

“Spreading Basavanna’s message would make people think and ask questions. Nobody wants that,” says Vishwaradhya Satyampete, a well-known activist. “The Lingayat revolution offered a full blown ideological alternative to core Hindu beliefs of inequality and discrimination. Kalburgi was deeply involved in reviving this tradition and was stopped. His murder was not the first attempt to curb Basavanna’s influence,” he adds.

His father Linganna Satyampete, a noted writer and Lingayat activist, died mysteriously in 2013 and there have been allegations in the media that the case was hushed up. Basava Marga, a popular digital magazine on Lingayats, edited by Satyampete was hacked in March this year. He did not keep any backup and content going back to many years was lost.

Rajur believes that Kalburgi’s research into the Lingayat tradition led to his demise. “He could speak the truth fearlessly and was killed as he brought this approach to the study of Lingayats.”

“The Hindutva groups, the Veerashaiva mathas, even many Lingayat mathas turned against him. He did not let that bother him as he believed in what he wrote,” says the close friend.

Kalburgi’s influence grows

Dr Patil says Kalburgi’s research had not made him popular in his lifetime. As his research started cleaving Lingayats from Hindus and even Veerashaivas, many of his colleagues started avoiding him.

It took a tragedy for his research to start making its way to the people. The assassination, the protests, the high profile media coverage and the police hunt that followed drew attention to his work. People started reading his research, scholars started writing books and holding seminars on him and Kalburgi became a hot topic for doctoral research.

As awareness about Kalburgi’s research grew, several Lingayat activists stepped in to spread his word. WhatsApp groups, Facebook pages, YouTube videos sprung up to make his books more accessible and expand their reach. The Jagatika Lingayata Mahasabha, which came up in 2018 to fight for separate Lingayat religion, the huge rallies that followed, the slightly subdued but continuing mobilisation, all carry Kalburgi’s ideological imprint. “His contribution to the separate Lingayat religion movement was tremendous,” says Jamdar.

Rajur says in the last 20 years there has been a spontaneous grassroot campaign to popularise Lingayat philosophy. Every year during the month of Shravana, Lingayat mathas organise Vachana renditions. “Now people are organising these renditions in their homes on their own, inviting their friends and neighbours. This month Vachanas were sung in 400 homes in Dharwad,” he says.

There is also a burst of digital activity around Vachanas and Lingayat philosophy. Every week there are several online events where people gather to learn or debate. In the rising tide of Lingayat activism, Kalburgi has a tangible presence. He not only produced authoritative editions of the Vachanas, but also showed how to interpret them in line with the true spirit of the founding movement. He hovers over reminding everyone that to be a Lingayat is not just about being religious in a particular way but to grow into a sensitive social being who works for the good of all. As Jamdar says, “Halakatti discovered Vachanas but Kalburgi taught them.”

“There is no question that more people are reading Vachanas and Kalburgi. But are they also imbibing his critical thinking and egalitarian outlook? There I have doubts,” says Dr Patil.